TODAY’S labour market report showed that the American economy created 156,000 net new jobs in August. That was a bit less than expected, but payrolls are still growing comfortably faster than the working-age population. Despite having created over 2m jobs in the last year, pushing unemployment below 4.5% for the last five months, wage growth remains muted, at around 2.5%, compared to more like 3.5% the last time unemployment was comparably low. In a recent article for the print edition, I anlysed one potential explanation for weak wage growth: retirements of high-earnings baby-boomers.

Scott Sumner has taken issue with the premise of my piece. He says there is no puzzle at all. Instead, slow wage growth is being caused by slow growth in nominal GDP (cash-terms spending in the economy) — “end of story”. He says I forgot about monetary superneutrality, the idea that in the long run, neither monetary policy nor changes in monetary policy affect real economic variables like unemployment. He quotes Miles Kimball:

Sometimes journalists discuss a zero output gap combined with too-low inflation as if such a situation were strange, but a range of different macroeconomic theories all have the property that a zero output gap is consistent with any constant inflation rate.

-

Is there a wage growth puzzle in America?

-

A Lebanese drama joins the fight to ban child marriage

-

Kenya’s high court annuls the presidential election

-

A scheme to let non-flyers through the security gates

-

Attitudes to Islam in Europe are hardening

-

Why transgender people are being sterilised in some European countries

Mr Kimball is right, of course. In the long run, an economy and its labour market can sustain any inflation rate in equilibrium. But, contrary to Mr Sumner’s argument, this does not tell us much about America’s economy today. The labour market is plainly not in equilibrium. It continues to add jobs faster than the population is growing. The question for policymakers is: how long can that continue?

Another way of putting the question is to ask what would happen if the Fed let nominal GDP grow a little faster. If no output gap remains, more nominal GDP growth would translate into more inflation, and hence into higher nominal wage growth (unemployment might also temporarily fell below its natural rate, a concept whose history I recently wrote about). Alternatively, it is possible that faster nominal GDP growth would lead to more job creation without sparking much inflation or wage growth, just as was possible when unemployment was higher.

Mr Sumner seems to think we are in the first world. In my view, we are in the second. That wage growth is disappointing is evidence that the economy has not yet reached the natural rate of unemployment (or perhaps the natural rate of employment, given that recent improvements in the labour market have come partly via higher labour market participation among women).

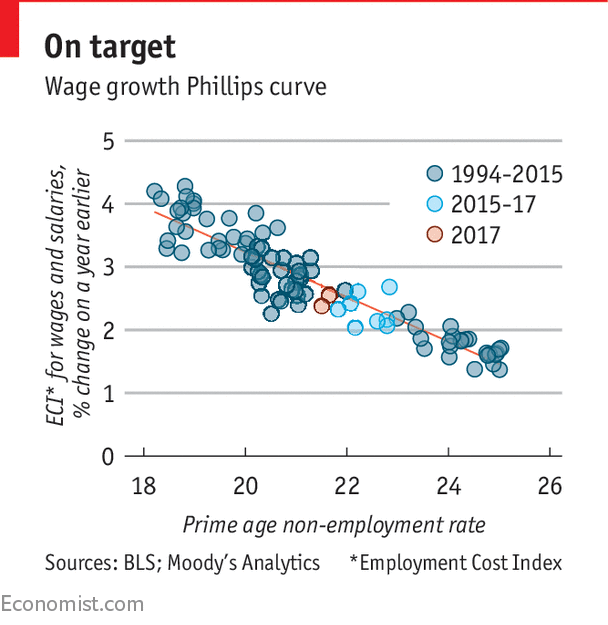

Mr Sumner’s view implies there is no output gap, the labour market is in equilibrium, and wage growth is low because inflation expectations have been low. I find this unconvincing, for two reasons. First, it means that unless the Federal Reserve brings job growth back in line with working-age population growth, inflation will soon rise. (Central banks cannot for long keep unemployment below its natural rate.) Yet inflation is in fact falling. Second, as Adam Ozimek at Moody’s Analytics has shown, wage growth as measured by the employment cost index is almost exactly where you would expect it to be given the employment-to-population ratio for 25- to 54-year-olds (see chart). If the rate of wage growth consistent with labour market equilibrium had changed to account for a shift in trend nominal GDP growth, you would expect this relationship to have broken down. It has not.

Janet Yellen’s critics tend to say she is excessively devoted to the idea that low unemployment portends higher inflation. They characterize this as adherence to the Phillips curve, which is associated in many peoples’ minds with Keynesian thinking. But it was monetarists who first argued that policymakers ultimately cannot control unemployment, because if loose money drives unemployment too low, inflation will accelerate. It is right for the Fed to look for the labour market for signals as to whether monetary policy is tighter or looser than the economy can sustain. Wage growth is the clearest of those signals. And it suggests that we are not in the long run yet.

Source: economist

Is there a wage growth puzzle in America?