President Donald Trump pledged to revive the coal industry and put miners back to work, but one year into his first term, there’s been little change in the beleaguered industry.

Coal production is up slightly and exports were a highlight in 2017, but coal-fired power plants are still closing. The best that can be said about employment is decades of job declines have bottomed out, which has also happened — temporarily — under past presidents.

This month, federal regulators dealt a blow to Trump’s energy agenda byrejecting his administration’s proposal to subsidize coal plants, its most proactive step to prevent more of them from shutting down.

To be sure, it would be a heavy lift for any president to reverse the structural decline in the coal industry. But Trump has tried by repealing President Barack Obama‘s signature plan to limit carbon emissions from power plants, scaled back other coal regulations and ended a moratorium on issuing leases to extract coal from federal lands.

Those regulations created hurdles for the coal industry, but the main problem remains competition from cheap natural gas and renewable energy, said Matt Preston, research director for North American coal markets at Wood Mackenzie.

“All of those hurdles would have been overcome if natural gas was really expensive … but with gas cheap, you just don’t go over those hurdles.”

“It’s a help, there’s no doubt about it,” he said, referring to deregulation. “But they’re not going to improve the economics of today.”

Luke Popovich, vice president of external communications at the National Mining Association, said he disagrees that Trump’s policies have been incidental or that the rebound has been modest.

“Had his administration prevailed with the Clean Power Plan, the moratorium on federal coal lease sales and the stream rule — all voided in this past year — coal communities and their employment would likely never have recovered,” he said. “That, to us, is the relevant and realistic measurement of coal’s comeback”

Here’s how coal performed on a number of fronts under Trump’s watch.

Coal production rose slightly during Trump’s first year in office. The country produced 767.4 million short tons of coal in the year through January 13, according to weekly estimates from the U.S. Energy Department.

That’s up 3.6 percent from the previous 52-week period — just before Trump took office — when output totaled 740.4 million short tons.

The main driver was steeper natural gas prices, which meant coal was more competitive with gas for electric power generation, analysts say. Coal and natural gas each account for about 30 percent of U.S. power mix. Coal eats into natural gas’s lead when gas prices rise.

Natural gas first overtook coal as the American grid’s primary fuel source in 2015 following a surge in its use in power plants. Its rapid rise is now moderating, analysts say.

“The market really bottomed out in 2016. We had incredibly low gas prices and they displaced more coal generation than at any time before,” said James Stevenson, senior director of global coal at IHS Markit.

“The overall trend is still very much down,” said Stevenson, referring to U.S. coal production. “2017 was a recovery year.”

The U.S. Department of Energy forecast that coal production will slip by 2 percent this year and next. That outlook is based on its projection that natural gas prices will remain low over much of the next two years and demand for U.S. coal exports will slow down.

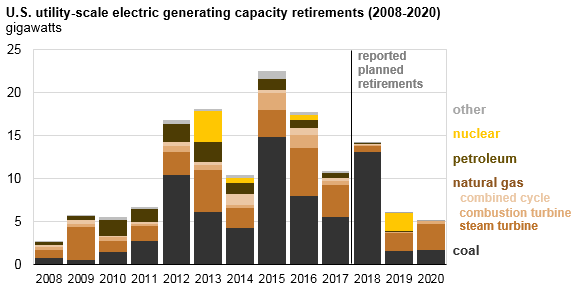

Most coal produced in the United States is burned in power plants, and the country continued to mothball coal-fired facilities under Trump.

The United States retired about 5.5 gigawatts of coal-fired power generation in 2017, down significantly from recent years, when many small, inefficient plants shut down as new pollution rules took effect. But more than double the amount of coal-fired generation that retired last year is scheduled to come offline this year.

Since Trump took office, 20 coal plants have announced they’re shutting down, according to a count by the Sierra Club, an environmentalist group.

There’s little chance new coal plants will open because natural gas facilities can be built cheaper and faster, says Stevenson. Utilities and independent power producers also anticipate greenhouse gas regulations will take effect at some point in the future.

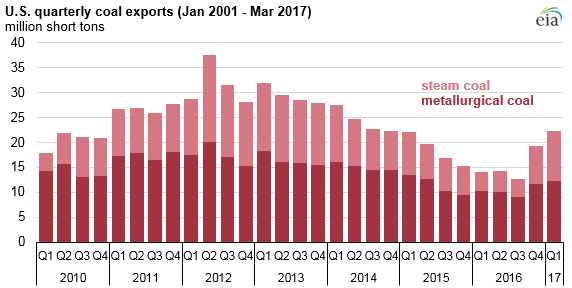

A bump in U.S. coal exports also boosted mining activity. Coal exports rose 55 percent to 44.1 million short tons in the first half of 2017.

Disruptions in Chinese and Australian coal supplies conspired with higher demand in parts of Europe and Asia to push up international coal prices last year, opening a window of opportunity for U.S. coal producers.

Despite Trump’s efforts to promote U.S. coal overseas, there is limited scope for export growth. The United States is a swing producer, meaning it typically picks up customers at times when demand is high and supplies from dominant exporters like Australia and South Africa are limited.

Preston says today’s high international coal prices will cause those major exporters to increase production and muscle out U.S. miners.

IHS Markit believes the world genuinely needs more U.S. coal, but any uptick in exports won’t be large enough to offset the drop in demand at home, said Stevensen.

The White House did not yet return a call for comment on this story.

Employment in coal mining is indeed trending higher under Trump. Analysts say that’s to be expected given the moderate rise in production.

The United States added more than 1,100 coal mining jobs in the first six months of 2017, according to a quarterly census. The rebound began in the final months of 2016, when Obama was still in office and coal prices started rising.

However, preliminary monthly data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that the gains have topped out, and employment is sliding back towards year-ago levels.

Given the size of the coal mining industry — about 51,000 employees — the change in employment in the bureau’s survey of employers was so small in the year through October that economists can’t say with certainty whether there was actually a net gain in jobs.

The United States has shed about 100,000 coal mining jobs over the last 30 years. Employment occasionally ticks up from year to year — including under Obama and George W. Bush — but there’s nothing to suggest the long-term trend is reversing.

Here’s what the employment picture in Trump’s first year looks like compared to the trend since Ronald Reagan’s second term:

Trump pledged to revive the coal industry, but little has changed one year into his first term