NESTLÉ is not easily rattled, to some investors’ chagrin. The world’s biggest food company accounts for about half of all sales of instant coffee, not to mention one quarter of grub for babies, dogs and cats. Thirty-four of its brands, including KitKat and Nespresso, earn over $1bn each. Yet many investors complain that Nestlé is falling behind, and this week Daniel Loeb, an American activist investor who runs Third Point, a hedge fund, gave voice to their concerns. On June 25th, in a letter, he attacked Nestlé’s “staid culture and tendency towards incrementalism”.

Third Point has acquired a small stake in Nestlé, less than 2% of the company. But it was enough to spark a jump of over 4% in the company’s share price on hopes that its bosses would respond. On June 27th Nestlé announced its own menu of changes—all unrelated, the company claimed, to the urging of any individual investor. Third Point will keep pushing for more.

-

How do you pronounce “GIF”?

-

The involuntary bumping of flyers is likely to be outlawed

-

An exhibition at the Design Museum in London shows colour in a new light

-

How whales started filtering food from the sea

-

Foreign reserves

-

Has “one country, two systems” been a success for Hong Kong?

The skirmish points to a basic question facing not just Nestlé but many of its peers: how should a consumer-goods giant operate? Big brands can no longer assert their dominance by securing spots on store shelves and spending millions on television ads. Now they must also succeed online and meet demand for “healthy” and “natural” fare. In rich countries, in particular, large companies are squeezed on one side by trendy upstarts and on the other by cheap private-label goods.

Looming over the industry is 3G, a private-equity firm that has slashed costs at companies such as Anheuser-Busch, a brewer, and Kraft Heinz, a packaged-food business. Investors debate whether these cuts undermine growth in the long term. But 3G has indisputably set a new bar for how profitable ageing consumer companies can be.

Confronted with this, Nestlé has been adapting slightly. Its chief financial officer, François-Xavier Roger, has said that he admires 3G, although Nestlé’s approach is different. The firm is cutting costs, yet it has not set a target for its profit margins, preferring to reinvest in long-term growth. For instance, Nestlé has poured money into understanding how food, pharmaceuticals and personal products might converge.

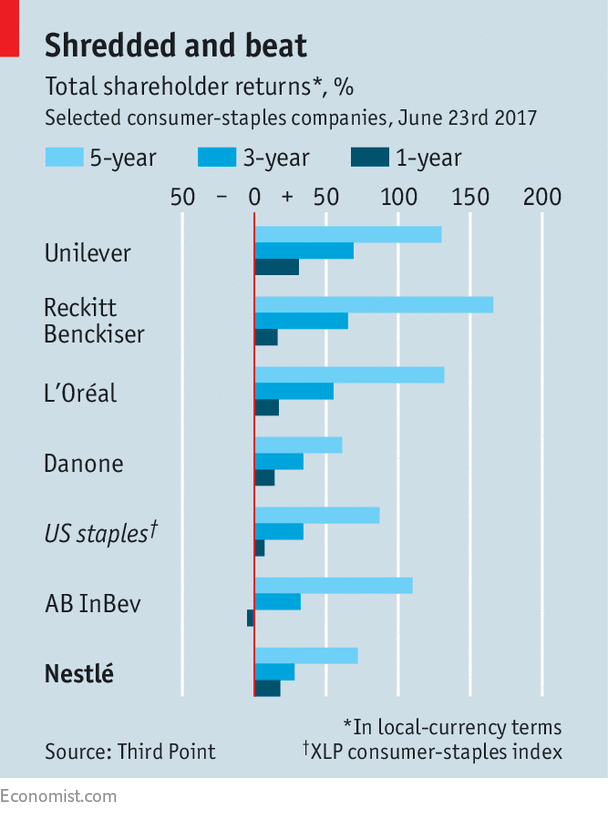

Mr Loeb is among those who want more immediate action. He points out that Nestlé’s total shareholder return lags that of its peers (see chart), though the strong Swiss franc makes Nestlé’s performance look particularly poor. Its 15% operating margin last year was lower than not just Kraft Heinz’s lofty 27% but a 16% margin at Unilever, an Anglo-Dutch giant, and 17% at General Mills, an American cereal maker, according to Sanford C. Bernstein, a research firm.

In January Ulf Mark Schneider, a former boss of a German dialysis firm, became Nestlé’s chief executive, the first outsider to lead the firm since 1922. He has scrapped Nestlé’s 5-6% annual growth target and said it might sell its confectionery unit in America, which has lost share to rivals. On June 27th Nestlé announced up to SFr20bn ($21bn) in share buy-backs by 2020. It promised to invest in zippy categories such as coffee and pet food.

Mr Loeb, who met Mr Schneider in early June, will ask for more, including a comprehensive review of Nestlé’s portfolio (to discard its weaker brands) and the sale of Nestlé’s 23% stake in L’Oréal, a French beauty-products firm. Most important, however, is his call for new discipline on spending, including cuts to Nestlé’s bureaucracy. That would help reach Mr Loeb’s target of 18-20% margins by 2020.

As Mr Schneider considers his next steps, he might consider the case of Unilever. Led by Paul Polman, an executive at Nestlé until 2008, Unilever fended off a takeover by Kraft Heinz in February. Mr Polman satisfied investors by announcing many of the changes recommended by Third Point for Nestlé, including the goal of a 20% margin by 2020. The company’s stock is up by 40% since the start of the year. Like Unilever, Nestlé may not need to consign its whole model to the bin.

Source: economist

An activist investor bites into Nestlé