APPLE has a new hit device, so popular that it has sold out across most of America and Britain. If you order it online it takes six weeks to arrive. “Best Apple product in a long time,” sings one online review. Useful and (of course) slickly designed, it enjoys the highest consumer satisfaction of any Apple product in history, according to a study by two firms, Creative Strategies and Experian.

Such enthusiasm must be bittersweet for Apple’s bosses. The gadget in question is AirPods, a set of wireless headphones that look a lot like Apple’s traditional ear buds, just without a wire. Priced at $159, AirPods could become a business worth billions of dollars, like the Apple Watch, a wearable device that Apple started selling in 2015. But headphones are hardly the transformative, vastly profitable innovation that many have been waiting for.

-

How do you pronounce “GIF”?

-

The involuntary bumping of flyers is likely to be outlawed

-

An exhibition at the Design Museum in London shows colour in a new light

-

How whales started filtering food from the sea

-

Foreign reserves

-

Has “one country, two systems” been a success for Hong Kong?

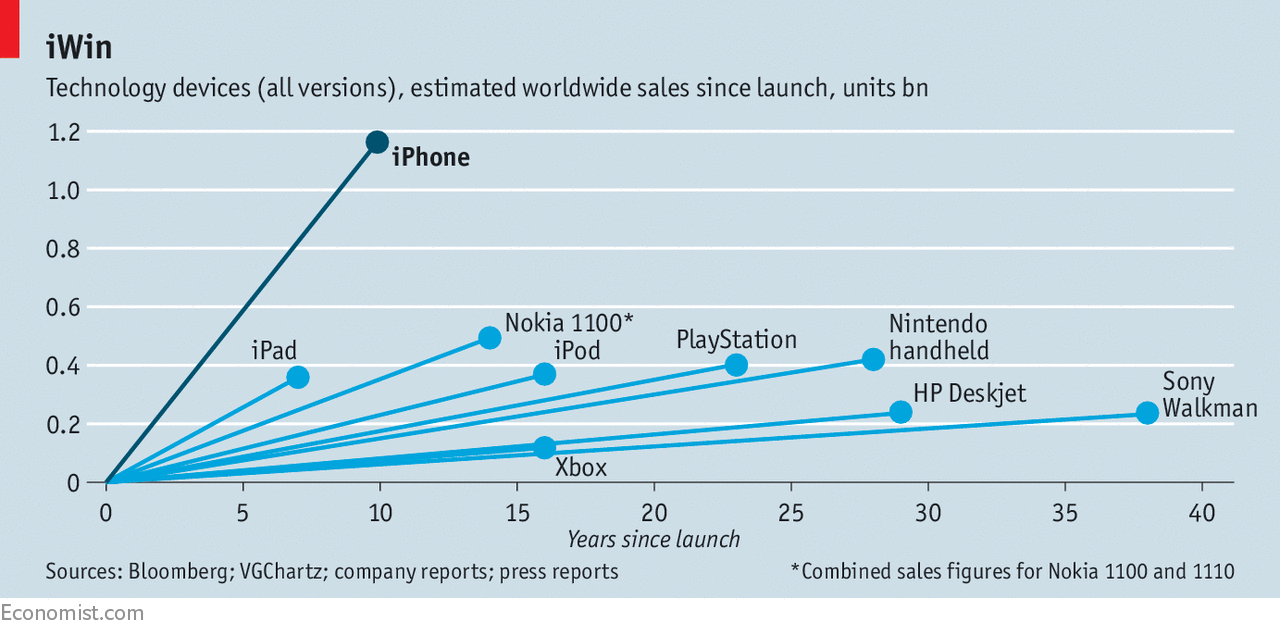

That wait started only a few years after its biggest blockbuster launched. On June 29th 2007 the iPhone first went on sale. Since then Apple has sold some 1.2bn phones and notched up more than $740bn in sales from the bestselling tech gadget in history (see chart). Two-thirds of Apple’s $216bn in sales in 2016 came from the iPhone.

Atop a hill there is usually nowhere to go but down. Questions about the future of the iPhone and whether Apple will ever design another product to match it pursue the company. The relentless rise of smartphone ownership is slowing, with around two-fifths of the global population now owning one. Apple is also facing more competition, especially in China (its second most important market after North America) where sales have been declining, lending weight to fears that Apple is experiencing “peak iPhone”.

Even though Apple has been spending $10bn a year on research and development, “people aren’t banking on innovation”, says Amit Daryanani ofRBC Capital Markets, a bank. That helps to explain why the firm’s shares are valued on a price-to-earnings ratio of around ten times its forecast 2018 earnings (stripping out cash), lower than the 12-14 times that the information-technology industry trades on.

Certainly, Apple’s attempts to diversify away from its hit product have been flawed. One disappointment has been television, worth some $260bn globally. ItsTV offering is a cable box that is little more than a portal to content from other firms, such as Netflix, not the disruptive offering that Apple executives promised.

There is also justified scepticism about another possible avenue for growth: personal transportation, an industry that is worth some $10trn. In June, for the first time, Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive, publicly discussed the firm’s ambition to develop an autonomous-car system. Apple could surely design a sleek car, but the big shift is away from ownership toward transportation as a service. Routing cars to specific places, as Uber does, is a leap.

Many people believe that Apple could expand in health care, on which people spend an estimated $8trn each year globally. Today Apple allows people to store their fitness information on their devices and offers a platform for developers to create health and fitness apps. But it is as yet unclear what Apple’s edge will be. Its stance on consumers’ privacy, which it protects more assiduously than other technology giants, may be an advantage. But dealing with a complex web of companies and reams of red tape, as any foray into health care would require, would again be a big departure from what it is used to.

Part of Apple’s difficulty in finding the next big thing may be that it is still steered by a small, insular group of executives who have mostly been at the firm since the 1990s. They include Mr Cook, who took over shortly before the death of Steve Jobs, the firm’s adored founder, in 2011. Apple is not good at hiring people from outside who could help bring new skills and ideas. Other companies have a far better record of bringing outsiders into the fold. Amazon’s Prime video offering and the work that formed the basis for Echo, its home speaker, drew on newcomers’ expertise.

Yet Apple will have every chance to adapt because of the enduring strength of its hit product. The iPhone business will not grow as rapidly as in the past but it will remain more important for far longer than people think, says Ben Thompson of Stratechery, a research firm. The iPhone 8, due to be unveiled in September, is likely to be innovative enough to encourage around 250m-300m iPhone users to upgrade, driving a new “supercycle” of sales.

Katy Huberty of Morgan Stanley, a bank, goes as far as to say that “for Apple the next iPhone will be the iPhone.” The inclusion of augmented reality (AR), which superimposes digital information onto real-world images, for example, is likely to drive strong future iPhone sales. Apple is likely to include a 3D camera in the iPhone, and it recently said it would begin operating ARKit, a platform for software developers to design new apps that integrate AR. This step is akin to when Apple launched its app store in 2008. That set off a wave of innovation in mobile apps, which in turn gave consumers more reasons to buy iPhones. One early experiment is by the retailerIKEA, which is working on an iPhone and iPad app that lets users point their phone and see what furniture looks like superimposed in a particular space.

By encouraging app developers to start work onAR now, Apple will have a two- or three-year head start on Google’s Android operating system, says Tim Bajarin of Creative Strategies. Google has launched anAR platform, called Tango, but it is only available on two devices, the Lenovo Phab 2 Pro and the Asus ZenfoneAR, which have few users. If Apple can keep a lead on integratingAR into its software, that would also give users a reason to keep on preferring the iPhone over cheaper smartphones. This will be particularly helpful in China, where local brands such as Vivo andOPPO have taken share—last summerOPPO’s R9 phone, which costs just $400, overtook the iPhone in the country.

Other revenue streams are tied in part to the iPhone’s success. One area of strong growth—if the base of iPhone users continues to expand—will be Apple’s services business, which includes revenue from app sales, cloud storage, insurance of Apple devices and more. Services are already Apple’s second-largest business, having overtaken personal computers in 2016.

Spec for smart specs

Another promising new business is smart glasses, which Apple has begun referencing in its patent applications. These will overlay digital information onto the real world without the need to look down at a screen. Work that Apple has done in developing AirPods, the Apple Watch andARKit, such as waterproofing and elongating battery life, are the building blocks for smart glasses, says Benedict Evans of Andreessen Horowitz, a venture-capital firm. Many reckon that glasses may render phones useless, but for a long while, glasses will only work with the help of the computing power of a nearby smartphone.

Yet it may be another question entirely—its use of data—that matters most to Apple’s next decade. Apple has made a point of distinguishing itself from firms like Alphabet, Google’s parent company, which mine user data to target ads online. It has made a great effort to make ad blockers easy for users to install, for example. But data are increasingly central to designing the smartest software; Apple already risks lagging behind in areas such as voice recognition and predictive software if it remains inflexible about hoovering up consumers’ information. Whether to prioritise privacy ahead of innovation may turn out to be Mr Cook’s most important decision yet.

Source: economist

The new old thing