HE WAS back in favour, or so it appeared. After spending several months under house arrest in late 2014, Vladimir Yevtushenkov, a Russian oligarch, relinquished control of Bashneft, a midsized oil firm, to the state. “If you like another company tomorrow and want to take it, you are welcome,” he told Vladimir Putin at the time, he later recalled. The president publicly gave his approval to Sistema, Mr Yevtushenkov’s conglomerate, shares in which had plunged. Mr Yevtushenkov subsequently appeared at annual Kremlin receptions and late last year joined a presidential delegation to Crimea.

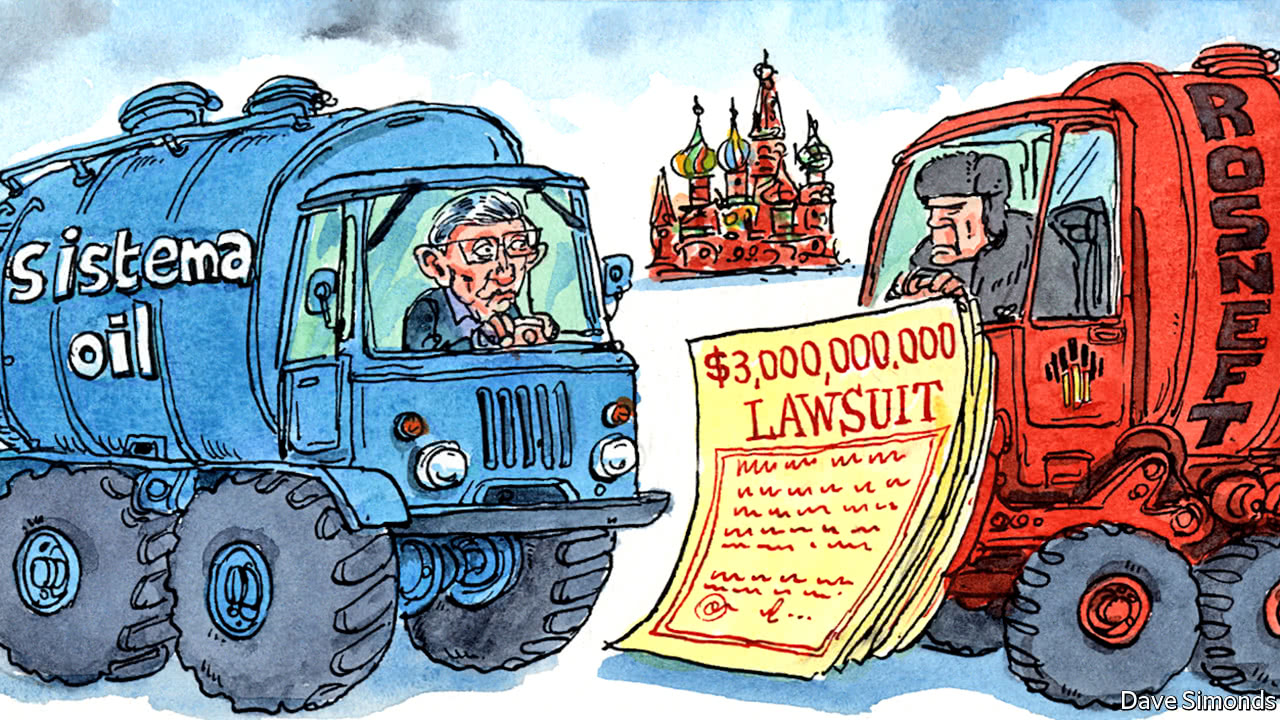

Now he is under pressure again, facing a lawsuit from Rosneft, a state-run oil giant, which is demanding 171bn roubles ($2.8bn) in damages. Rosneft’s boss is Igor Sechin, a Putin confidant, who many in Moscow reckon orchestrated the initial 2014 case against Mr Yevtushenkov as well. (Rosneft and Mr Sechin have denied any involvement in it.) Late last year, Rosneft purchased Bashneft from the state for $5.3bn. It now claims that Sistema inappropriately took assets in a restructuring of Bashneft.

-

Brazil’s army is becoming a de facto police force

-

Why British Airways customers might enjoy a strike by flight attendants

-

Obituary: Joel Joffe died on June 18th

-

A new play explores the genesis of Britain’s titanic tabloid

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

The case attests to Rosneft’s appetite for deals, as well as to Mr Sechin’s clout. Since acquiring Bashneft, Rosneft has sold a 19.5% stake in itself to Glencore, a Swiss-based commodities firm, and the Qatar Investment Authority for €10.2bn ($11bn), despite being a target of American sanctions. Mr Sechin also just concluded a deal worth $12.9bn to acquire India’s Essar Oil. A Rosneft spokesman, Mikhail Leontyev, says “there’s nothing personal” about its case against Mr Yevtushenkov’s firm, even if many in Moscow’s business community see the affair as a clash of titans.

The assets that Sistema is alleged to have taken from Bashneft include an energy supplier held by a subsidiary. Rosneft also asserts that Bashneft incurred damages as a result of Sistema’s decision to buy out Bashneft’s minority shareholders during the 2013-14 restructuring and because it cancelled some treasury stock in the firm. Sistema calls the case “groundless”. Under its ownership, it notes, Bashneft’s market value rose eightfold and its production of oil rose by nearly half. “Investors were largely happy,” says Andrey Polischuk, an oil-and-gas analyst at Raiffeisen Bank.

Investors in Russia will watch the suit closely. It underlines the frailty of property rights, says Oleg Kouzmin, an economist at Renaissance Capital, an investment bank in Moscow. Sistema’s shares lost more than one-third of their value the day after the suit was filed in early May. Late last month a court seized as collateral Sistema’s shares in MTS, Russia’s largest mobile operator; in Medsi, a private medical clinic; and in an electrical company in Bashkiria.

The conflict also hints at rising tensions inside Russia’s elite as the economy continues to sputter. The chieftains are fighting each other, observes Mikhail Krutikhin of RusEnergy, a consultancy. Russia’s formal institutions have long had a tendency to falter, but a system of unwritten rules, known as ponyatiya, understood both by local players and foreigners, has helped govern business dealings. Thus Mr Yevtushenkov, who is loyal to the Kremlin and stays out of politics, was widely considered to be in favour before his initial arrest. His reconciliation with Mr Putin was expected to put him back on firmer ground. As Sistema’s CEO, Mikhail Shamolin, said recently, “In terms of ponyatiya, there are no claims to be made against us.”

“It is unclear what the rules are now,” laments Konstantin Simonov, head of the National Energy Security Fund, a consultancy. Independent members of Sistema’s board have asked the Kremlin to act as an arbiter, but Mr Putin has largely remained silent on the matter. Some people say the conflict is a new version of the corporate-raiding culture of the 1990s, but carried out with lawyers and court briefs instead of the earlier period’s methods, including henchmen toting Kalashnikovs.

Source: economist

Russian oligarch Vladimir Yevtushenkov falls from grace, again