THE European Commission celebrated 25 years of the EU’s internal aviation market in June. The liberalisation of European aviation, which allowed EU carriers to fly between any airport within the bloc, opened the skies to the masses. Greater choice of airlines has cut fares—by as much as 96% between Paris and Milan since 1992, for example, in large part because of low-cost carriers (LCCs). Cheap fares have pushed passenger volumes to record levels, from 360m in 1993 to 920m this year.

Yet the bosses of Europe’s two biggest LCCs, Ireland’s Ryanair and Britain’s easyJet, are in no mood to cheer. The problem is the possibility of a hard Brexit. In the 1990s Britain was the country driving forward airline liberalisation in Europe, against the instincts of France and Italy, which preferred to protect their own flag carriers. The British government’s plan to leave the EU by March 2019 means that the country will probably exit the European Common Aviation Area (as an expanded version of that initial aviation market is known). Continued membership would require acceptance of European court jurisdiction, a “red line” for British negotiators. Without a new agreement to replace it, flights between Britain and the EU might have to stop entirely, says Michael O’Leary, the chief executive of Ryanair.

-

Obituary: Joel Joffe died on June 18th

-

A new play explores the genesis of Britain’s titanic tabloid

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

What is the OECD?

-

How to teach civics in school

Other airline executives do not think a complete stop in flights is on the cards. Negotiators on both sides have an incentive to avoid howls of protests from Britons denied summers in the sun and Mediterranean hoteliers left with empty resorts. Even if a permanent arrangement is not forged in time, some sort of interim deal to allow existing Britain-EU routes to continue after Britain leaves seems likely.

But Mr O’Leary is right to worry. Brexit is likely to create a worse environment for many European airlines. Growing rates of migration among young people in the bloc have boosted revenues. The share of passengers flying within the EU to see friends and family, rather than for tourism, has grown from 5% in the early 1990s to around a third. Restrictions on migration between Britain and the EU could sap demand.

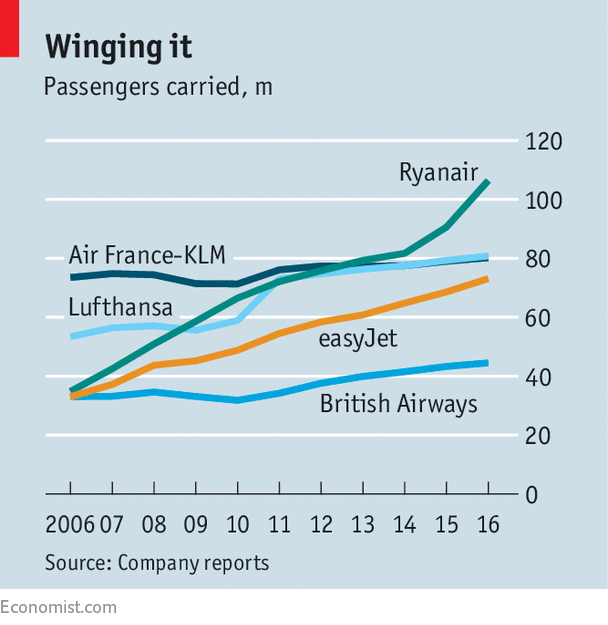

Budget airlines have the most to lose. In the past decade, LCCs have been responsible for 99% of the increase in passenger traffic at Europe’s 20 biggest airports, according to Olivier Jankovec of ACI Europe, an industry group. Bringing competition to routes once dominated by cosseted national carriers, they stimulated demand by slashing fares.

Now their full-service rivals scent a chance to grab back some business. The flag carriers of France and Germany, which have a close relationship with their respective governments, have every incentive to make sure that rivals are caught by rules that ban foreign airlines from flying within the EU, says Andrew Charlton of Aviation Advocacy, a consultancy. In February Lufthansa’s CEO, Carsten Spohr, said he will oppose any attempt by easyJet or British Airways to re-enter the European Common Aviation Area after Brexit.

Even if an interim deal is reached to continue flights between Britain and the EU, it is possible that Ryanair will be prevented from flying within Britain and that easyJet, a British carrier, will be unable to fly within the EU. In March 2019 they may each have to split themselves into a British-registered firm and one based in the EU.

The LCCs are famously flexible. They can move aircraft around their networks in a way that legacy carriers that base their operations around specific hub airports cannot. This sort of response enables them to respond to temporary disruptions. But if Britain cannot forge a deal to replace the European Common Aviation Area, there will be fewer airlines on many routes. And that will be to the detriment of both British and European passengers.

Source: economist

Why Brexit could entail a hard landing for low-cost carriers