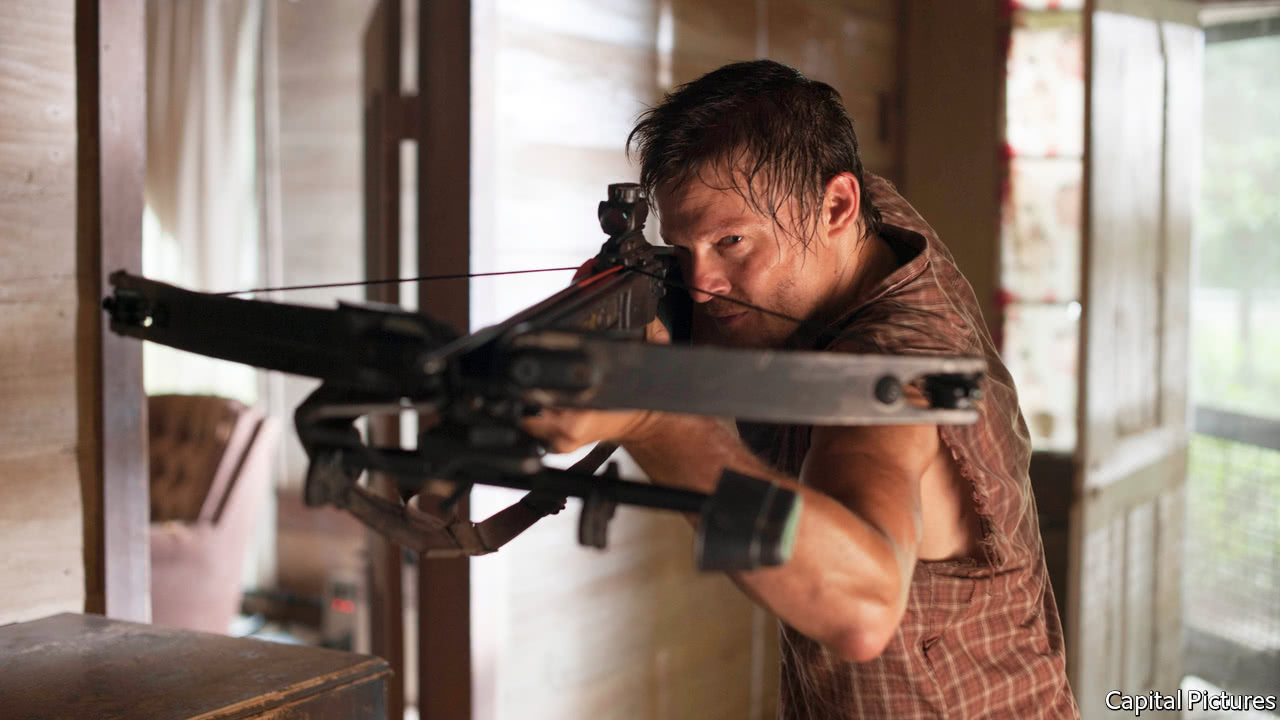

WHAT is the best way to kill a zombie? Fans of Daryl Dixon, a character in “The Walking Dead”, a television series, will know the answer: a crossbow bolt to the brain. Getting rid of corporate zombies, however, is a much more complicated process.

Ageing populations mean that the workforces in developed economies are likely to stagnate, or even shrink, in coming decades. That means almost all the burden of economic growth is likely to fall on productivity improvements. There has been a lot of focus on labour-market flexibility as the key to solving this problem, but the flexibility of the corporate sector may be just as important. Indeed, there is a growing belief that the persistence of zombie firms—companies that keep operating despite a poor financial performance—may explain the weak productivity performance of developed economies in recent years.

-

Revolutionary music, from rousing to mindless

-

Catalonia plans to hold an independence vote whether Spain lets it or not

-

Who is writing politicians’ letters complaining about the Gulf carriers?

-

Blood from young animals can revitalise old ones

-

The cliché that tennis is a sport of matchups is probably right

-

Why Democrats are taking aim at gerrymandering

An inability to kill off failing companies seems to have two main effects. First, the existence of the zombies drives down the average productivity level of businesses. Second, capital and labour are wrongly allocated to such firms. That stops money and workers shifting to more efficient businesses, making it harder for the latter to compete. In a sense, therefore, the corporate zombies are eating healthy firms.

One definition of a zombie company is a business whose earnings before tax do not cover its interest expenses. The latest annual report from the Bank for International Settlements examines 14 developed countries and finds that, on this measure, the average proportion of zombies among listed companies increased from less than 6% in 2007 to 10.5% in 2015.

That analysis builds on the work of an OECD paper published earlier this year which found that, within industries, a higher share of capital invested in zombie firms was associated with lower investment and employment growth at healthier businesses. A new paper from the OECD examines the link between zombie firms, capital misallocation and the design of corporate-insolvency regimes.

The idea is simple. The easier it is for companies to become insolvent, the more quickly capital can be reallocated from inefficient to efficient uses. The OECD paper highlights 13 key features in insolvency regimes, including personal costs to failed entrepreneurs, the rights of creditors and the ability to distinguish between honest and fraudulent bankruptcy. The authors circulated a questionnaire on these issues within 35 OECD member countries and 11 non-member states; 39 responded. It then constructed a set of indicators based on the survey responses.

Britain was the country with the best-designed insolvency regime, based on these criteria; Estonia had the most cumbersome set-up. (America was ranked sixth, behind Britain.) Sure enough, the study finds that insolvency regimes that make it easier to restructure companies, and limit the personal costs associated with entrepreneurial failure, reduce the amount of capital tied up in zombie firms. Dispatching the living dead on TV and in movies may require the maximum amount of brutality; when it comes to the corporate undead, it is best to kill with kindness.

This is an important issue. The OECD estimates that, in 2013, the share of capital sunk in Greek zombie firms was 28%. The figures for Italy and Spain were 19% and 16%, respectively. Countries seem to have realised the need for change; 15 of the countries surveyed have changed their insolvency regimes in recent years. The authors reckon that a further shift in regime towards the British model could reduce the zombie-capital share by at least 9 percentage points in some countries.

There is a lot more to the productivity puzzle than just the nature of insolvency regimes; weak productivity is a big concern in Britain, for example. It seems clear that a squeeze on real wages in recent years has meant that companies in some industries have been happy to employ more workers rather than buy productivity-enhancing machines. And Robert Gordon of Northwestern University has suggested that innovations like the internet have been less transformative for productivity than previous developments such as electrification and the internal combustion engine. But the idea that the corporate sector is becoming more ossified, as seen in the decline of new business formation, deserves a lot more attention.

Source: economist

How to kill a corporate zombie