A DECADES-old dream of many low-cost carriers (LCCs), to break into the market for long-haul flights, has also been a long-standing nightmare for executives at full-service airlines, who earn their corn chiefly on such routes. So a series of setbacks for Norwegian, the latest LCC to try its hand at long-haul flights, has set off a round of Schadenfreude at established airlines across Europe. On July 13th, Norwegian revealed a disappointing set of results for the three months to June. A week earlier its chief financial officer of 15 years, Frode Foss, resigned with immediate effect, sending the share price down by 8%. Over the past year the shares have lost a third in value, as investors grow nervous.

The worries go back to Norwegian’s decision to begin long-haul flights. Founded in 1993 by Bjørn Kjos, still its CEO and biggest shareholder, it took over some domestic routes in Norway from a bankrupt charter airline, Busy Bee. Then in 2002 it went into short-haul flights in Europe, becoming the continent’s third-largest LCC. After a few years of decent profits, in 2012 Norwegian ordered 222 new planes that together cost several times its own value, and announced its new “no-frills” long-haul routes to America and Asia.

-

Rugby union’s rules and regulations let the sport down

-

The Big Mac index

-

The joy of hypotheticals

-

Wimbledon’s rapid grass courts have been less speedy this year

-

Donald Trump’s effect on tourism has not been as bad as feared

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

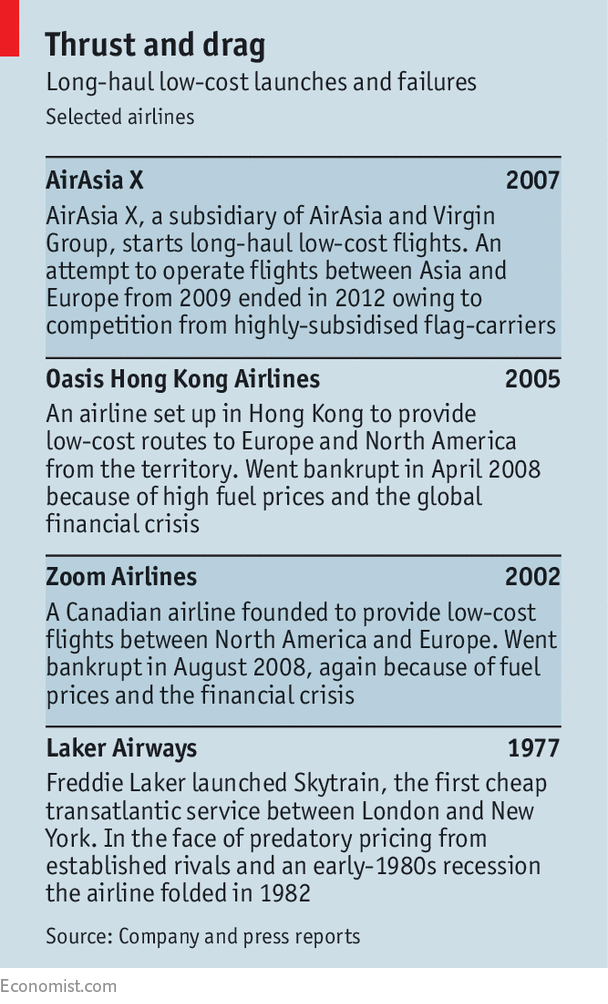

Investors were sceptical. Many LCCs have gone under trying to enter the long-haul market (see table), or had to admit defeat. The pioneer of no-frills transatlantic flights in the 1970s, Sir Freddie Laker, could not make his ventures work. Mr Kjos sees Laker as an inspiration; this spring Norwegian painted his face on one of its jets.

Yet changes in aircraft technology, consumer tastes and workers’ benefits mean that the long-haul low-cost model has a better chance of working today. Andrew Charlton of Aviation Advocacy, a consultancy, notes that new, fuel-efficient aircraft, such as the Boeing 787 and 737MAX aircraft purchased by Norwegian, mean it is now possible to fly smaller numbers of passengers over long distances at relatively low cost. Passengers have grown accustomed to low-cost carriers (LCCs)—which fly more than two-fifths of all passengers within Europe each year—and are more willing than in the past to try out no-frills airlines on longer routes, too. A third factor helping low-cost long-haul travel is that airlines are less encumbered by generous labour contracts and unfunded pension costs than before. Some LCCs, such as Scoot, owned by Singapore Airlines and Jetstar, owned by Australia’s Qantas, using similar tactics to Norwegian, are making a fist of low-cost long-haul flights.

In the case of Norwegian, however, investors worry that the investment it has made in its long-haul business could swamp its balance-sheet, says Ross Harvey of Davy, a stockbroking firm in Dublin. It is more highly leveraged than other European airlines—shareholders’ equity accounted for 11% of its assets last year, compared with 35% for Ryanair, Europe’s largest LCC, and 49% for easyJet, the second-biggest. It also has relatively low cash reserves and fairly thin profit margins.

That may make it difficult to withstand the shocks that regularly beset the aviation sector. An event such as a terror attack that reduces passenger numbers or a sudden increase in fuel prices would hit Norwegian hard. An approaching crunch over the next year, when Norwegian has to pay for 19 new A320neo jets that it cannot currently use or lease because they have engine problems, may explain the CFO’s sudden departure, says Bjorn Fehrm of Leeham Company, a consultancy: “he would not want to be around to sort this mess.” In a statement Mr Kjos said it was understandable that Mr Foss would wish to concentrate on “other tasks” after 15 years at Norwegian.

If Norwegian gets into trouble, there is at least an obvious solution: a takeover by a rival with deeper pockets. Ryanair and easyJet are not interested because they do not want to complicate their business models. But Willie Walsh, the boss of IAG, a London-based group made up of several flag-carriers, seems eager to take on Mr Kjos in the low-cost long-haul market. British Airways, one IAG airline, has started to run cheap long-haul flights on the same routes as Norwegian from London’s Gatwick. In March IAG launched Level, a long-haul LCC, in Barcelona, to fight off Norwegian’s new long-haul hub there. The gossip among analysts is that IAG is readying itself to snap up its rival if it weakens further. If full-service airlines can’t beat LCCs, the answer may be to join them.

Source: economist

Norwegian might still transform long-haul flying