THIRTY-ONE years ago, The Economist created the Big Mac index as a way of gauging how different currencies stacked up against the dollar. The index is based on the theory of purchasing-power parity, the idea that in the long run, exchange rates should adjust so that the price of an identical basket of tradable goods is the same. Our basket contains one item, a Big Mac.

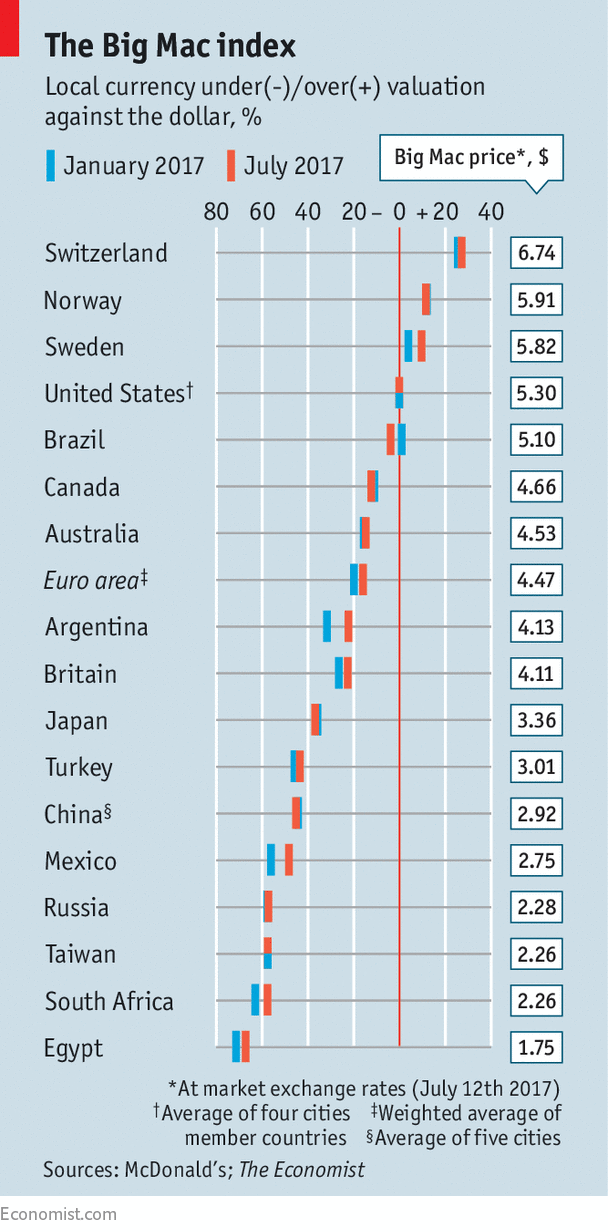

The latest version of the index shows, for example, that a Big Mac costs $5.30 in America, but just ¥380 ($3.36) in Japan. The Japanese yen is thus, by our meaty logic, 37% undervalued against the dollar.

-

Rugby union’s rules and regulations let the sport down

-

The Big Mac index

-

The joy of hypotheticals

-

Wimbledon’s rapid grass courts have been less speedy this year

-

Donald Trump’s effect on tourism has not been as bad as feared

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

In that, the yen is not alone. The greenback has strengthened considerably in recent years: of the 34 currencies we track in the full index, 31 are currently undervalued against the dollar. Only the Swiss franc, Norwegian krone and Swedish krona are overvalued. That said, plenty of currencies have clawed back some ground against the dollar in the past six months.

Take, for example, the Egyptian pound, which burgernomics holds to be the most undervalued currency. In November, the Egyptian government decided to allow its currency to float freely. By December the pound had fallen to its current value of around 18 per dollar. Inflation has soared as a consequence, averaging 30% over the past six months. Big Mac prices have increased accordingly, from 27.5 pounds ($1.53) to 31.4. The net result, according to our index, is that the Egyptian pound has gone from 71% undervalued against the dollar in January to 67% today.

The euro has also gained ground in the same period. The single currency buys $1.14 today, up from $1.05 at the start of the year; the euro has gone from being 20% undervalued against the dollar in our index, to 16% undercooked. That reflects a mixture of politics and economics. Eurosceptic parties were beaten back at the polls in both the Netherlands and France, muting fears that populists would find success. The euro zone grew substantially faster than the American economy in the first quarter, and the European Central Bank has started to signal that its policy of extraordinary monetary stimulus will not last for ever. If Europe’s recovery continues to strengthen, American tourists to the continent may end up getting less burger for their buck.

One of the best-performing currencies over the past six months has been the Mexican peso. In January, the peso had fallen to a record low of 22 to the dollar, thanks in no small part to fears of a possible trade war with Mexico’s northern neighbour. But markets have become increasingly sceptical that Donald Trump will follow through on his most blood-curdling trade threats. The peso has recovered ground and hovers at around 18 per dollar. The Mexican currency is now only 48% undervalued against the greenback, compared with 56% in January.

Markets are also losing faith in Mr Trump’s ability to pass domestic economic reforms. On the campaign trail, the president-to-be promised expansionary fiscal policies, including tax cuts and increased infrastructure spending. Traders believed that the Federal Reserve would be forced to increase interest rates in response. The dollar surged, reaching a 15-year high in January. Since then, the dollar has slipped by 5% on a trade-weighted basis. That not only vindicates those sceptical of Mr Trump’s legislative prowess. It’s also a partial vindication for believers in burgernomics. If our index has any fact content, the dollar may have further to fall.

Source: economist

The Big Mac index