IN THE litany of bosses’ gripes about Brazil’s inclement business climate, rigid labour laws vie for pride of place with its convoluted tax laws and its licensing rules (on everything from health and safety to protection of cultural heritage). No wonder: Brazil ranks a miserable 117th out of 138 countries on labour-market efficiency, according to the World Economic Forum. Its rigid labour law was transplanted from Benito Mussolini’s Italy in 1943. Employers find it thoroughly unsuited to a modern economy and cheered on July 13th, when the president, Michel Temer, signed into law the biggest overhaul of the unwieldy statute in 50 years.

The reform is a big victory for the unpopular Mr Temer, who is under investigation in a corruption scandal (he denies wrongdoing). It introduces more flexible working hours, eases restrictions on part-time work, relaxes how workers can divvy up their holidays and cuts the statutory lunch hour to 30 minutes. It also scraps dues that all employees must pay to their company’s designated union, regardless of whether or not they are members. Just as important, collective agreements between employers and workers will overrule many of the labour code’s provisions.

-

The Supreme Court says grandparents are exempt from the travel ban

-

“City of Ghosts” is an extraordinary look at journalism in Raqqa

-

A papal confidant triggers a furore among American Catholics

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

Some good news and some bad, in the fight against HIV

Once the new rules take effect in four months’ time, they will be valid for existing employment contracts, not just new ones. Mr Temer hopes they will dent Brazil’s unemployment rate, stuck above 13% after a three-year recession.

Bosses are ecstatic about the changes. The National Confederation of Industry said that the reform represents “longed-for progress”. Banco Santander, a Spanish-owned bank, said it reckons the reform could eventually lead to the creation of 2.3m new jobs.

Small firms also have much to gain. The new rules “formalise what we now do informally”, enthuses a São Paulo caterer. The “bank” of actual hours worked by her cooks and waiters, necessary in a business where inflexible nine-to-five contracts make little sense, will now be legal. An executive at a European multinational says that an unofficial spreadsheet that keeps track of his employees’ real time off, which he confesses to maintaining alongside an official tally of employees’ annual 30 vacation days, can also be consigned to the dustbin. (The old law said that leave had to be split into at most two segments, with one holiday lasting at least 20 days.)

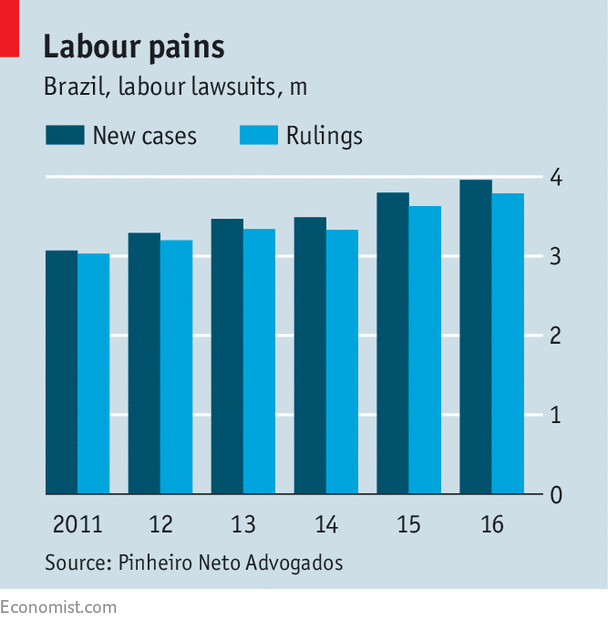

Such ruses have been common in Brazilian workplaces, but are risky. Employees who leave or are laid off regularly sue employers over the slightest of transgressions of the labour code, spurred on by litigious lawyers. Last year Brazil’s labour courts heard nearly 4m cases (see chart), mostly brought by aggrieved workers. Fines levied on firms totalled 24bn reais ($7bn).

The reform ought to reduce such legal risks, which can afflict firms whether they observe the rules or not. Gabriel Margulies, whose company, UnderMe, produces 50,000 pairs of undergarments a month, says he will at last be able to grant requests to staff who would prefer, say, to go home early in exchange for a shorter lunch break. Until now he has declined for fear of losing in court. That has not stopped former employees from suing in the hope that Brazil’s famously worker-friendly judges side with them. Even unsuccessful suits are an unwelcome distraction from running a business, Mr Margulies laments.

Maurício Guidi of Pinheiro Neto, a firm of lawyers, observes that the reform might even change this confrontational workplace culture into a more consensual one. But it remains to be seen how the labour unions will react, notes Marcelo Silva, vice-chairman of Magazine Luiza, a big retailer. The main union confederations have condemned the reform. They fume about the loss of revenue from dues. To placate them, Mr Temer has hinted he may amend the reform by decree, which is subject to a simple up-or-down vote in Congress, in order to phase out the obligatory dues gradually (and possibly water down some other provisions). But he cannot go too far. The only way for the scandal-hit president to keep his job may be to help some of his 13.8m unemployed compatriots find work.

Source: economist

An overhaul of Brazilian labour law should spur job creation