“PRETTY close to a laughing stock.” That is Walter Shaub’s verdict on America’s standing in the world, at least from an ethics point of view, under President Donald Trump. Mr Shaub’s view counts: he stepped down this week as head of the Office of Government Ethics, a federal watchdog.

He is leaving his job six months early, frustrated at the president’s failure to separate himself from his businesses, at White House foot-dragging on disclosing ethics waivers for staff, at its failure to admonish a Trump adviser who plugged the family’s products in an interview, and more. “It’s hard for the United States to pursue international anticorruption and ethics initiatives when we’re not even keeping our own side of the street clean,” Mr Shaub told the New York Times.

-

In America, who you are is what you eat

-

The Supreme Court says grandparents are exempt from the travel ban

-

“City of Ghosts” is an extraordinary look at journalism in Raqqa

-

A papal confidant triggers a furore among American Catholics

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

No American leader has ever entered office with such wide business interests as Mr Trump. In the context of the country’s corporate landscape, his group is small, mostly domestic and rather mediocre, but encompasses hundreds of firms that run hotels, golf courses, licensing agreements, merchandise deals and more, in over two dozen countries. Keeping tabs on the potential for self-dealing is “a monumental task”, says Kathleen Clark, an ethics expert at Washington University. In some areas, particularly abroad, increased scrutiny appears to be making deals harder to pull off. But in others, such as his American hotels and golf clubs, Mr Trump already appears to be monetising the presidency.

On becoming president, Mr Trump put his businesses in a trust. But it is run by two of his sons, Eric and Donald junior, and it is “revocable”, meaning its provisions can be changed at any time. Eric has since said he will update his father with profit reports, even though Mr Trump pledged not to talk business with his children while in office. Mr Trump, the Trump Organisation and his daughter, Ivanka, who owns a fashion business and is a White House adviser, have all hired ethics advisers to review deals for potential problems. But how the process works is opaque.

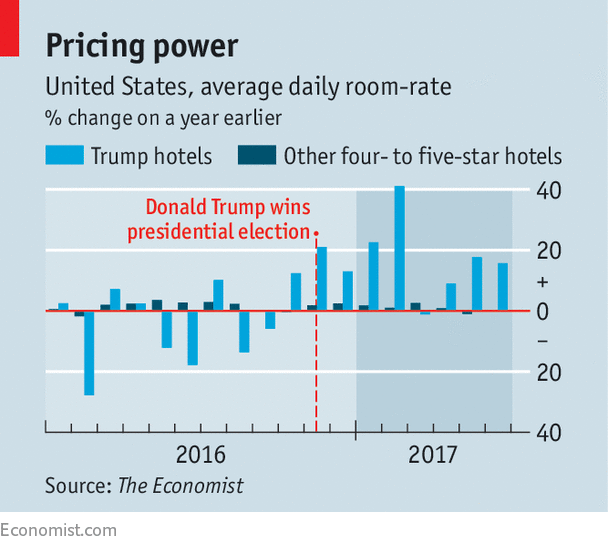

Mr Shaub was unimpressed by Mr Trump’s appearances at his own for-profit properties, which he has visited more than 40 times as president—most recently to attend the US Women’s Open, held this month at one of his golf clubs, in New Jersey. The visits serve as a form of marketing, and his firm has not been shy about cashing in. Mar-a-Lago, a Trump resort in Florida where the president hosts other world leaders, doubled its initial fee for new members to $200,000 after the election. The club made a profit of $37m in the latest reporting period (January 2016-spring 2017), compared with $15.5m in 2014-15.

When Eric Trump opened a golf course at Turnberry in Scotland in June, he said his family had “made Turnberry great again”. Staff wore “Make Turnberry great again” hats—a reference to Mr Trump’s campaign slogan and, critics say, an attempt to cash in on his political power. Eric recently said: “Our brand is the hottest it has ever been…the stars have all aligned.”

American golf courses have benefited from at least one of Mr Trump’s policy decisions: his move to scrap a proposed environmental rule crafted to protect drinking-water supplies. The national golf-course association had long lobbied to have the regulation ditched, arguing it could have “a devastating economic impact”.

With some Trump projects, the benefits could flow the other way, from business to politics. Take a network of budget hotels, branded “American Idea”, dreamed up by the Trump sons on the campaign trail last year. They have signed letters of intent with developers in numerous cities, including four in Mississippi. Bringing jobs to Republican-leaning states that are struggling economically could further boost support for the president in such places.

Mr Trump’s appointments also cause concern. He has picked Lynne Patton, a former event-planner for the family, to run the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s regional office covering New York. In that role Ms Patton will oversee Starrett City, a housing development that is part-owned by the Trump Organisation and that receives federal subsidies.

Foreign deals are no less troubling. The ethics plan laid out by Mr Trump in January promised no new foreign contracts during his presidency. But his company will press ahead with projects already in the works. There are many: an estimated 159 of the 565 Trump firms do business abroad. Some license the Trump name for skyscrapers and hotels, often to politically connected local partners.

An example of how such deals raise questions about Mr Trump’s motives is the current Gulf spat over Qatar’s alleged support for terrorists. Mr Trump has firmly backed Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and others in their boycott of their neighbour. It is reasonable to ask if it is a coincidence that he has strong business ties with the Saudis and Emiratis but few with Qatar. Saudis are big buyers of Trump apartments, and the kingdom is investing $20bn in an American infrastructure fund. A Trump-branded golf course in the UAE made Mr Trump as much as $10m in 2015-16. By contrast, Mr Trump’s past efforts to break into Qatar have failed.

Tracking such business relationships is not easy because of the opacity of Mr Trump’s holdings. He makes liberal use of LLCs—anonymous shell companies that do not have to publish financial information—often in complex combinations with regular corporations. He has refused to publish his tax returns.

A fog surrounds those doing business with the Trumps, too. Many have grown less transparent of late. An investigation by USA Today found that the percentage of buyers of Trump condos structuring their purchases through LLCs has jumped from single digits to two-thirds. Suppliers are scuttling into the shadows, too. Those shipping goods to Ivanka’s businesses in America typically identified themselves on bills of lading before the Trump presidency. Now they usually do not.

The Trumps’ fallback position is that, legally speaking, it is impossible for the president to be conflicted because he is exempt from ethics laws. The thinking when Congress blessed this exemption, in the 1980s, was that the president’s remit is so broad that any policy decision could pose a potential conflict. Nevertheless, some see avenues of attack. Several lawsuits, including one from Democratic lawmakers, accuse Mr Trump of causing harm by violating the constitution’s Emoluments Clause, which forbids American officeholders from accepting money from foreign governments. One way he allegedly does so is by accepting payments from diplomats at his hotels.

The lawsuits particularly focus on the newly refurbished Trump International Hotel in Washington, DC. Owned by the federal government, the hotel’s lease agreement includes a provision barring elected officials from holding an interest. But the General Services Administration, which manages federal property, ruled in March that Mr Trump’s 60-year lease on the hotel did not breach that requirement since the property had been placed in a trust (as long as he received no proceeds while president). Having initially said it would donate all hotel profits from foreign officials to the Treasury, the Trump Organisation now says requiring such guests to identify themselves would be “impractical” and “diminish the guest experience”.

Unpresidented

It remains unclear whether controversial transactions such as these will add greatly to the Trump empire’s profits. Deals are often smaller than you might imagine: the developer behind Trump Tower in Mumbai, founded by a member of India’s ruling party, paid just $5m for the licence. Some deals are being scrapped under scrutiny—as was the case, in January, with a tower in the Black Sea resort of Batumi.

Moreover, forces beyond Mr Trump’s control are likely to have a bigger impact on his businesses’ profits than conflicted dealmaking. A recent analysis of his properties by Bloomberg found that his three flagship office blocks in Manhattan—Trump Tower, 40 Wall Street and 1290 Avenue of the Americas—are making less money than envisaged when loans were issued, because of the softening of the New York office market. The combined present value of the three blocks has fallen by an estimated $380m over the past year.

Mr Shaub believes that Mr Trump has rejected ethical norms embraced by all other administrations since the 1970s. He recommends several changes to federal law, including greater powers for the oversight office and stricter disclosure rules. Rightly so. Whether or not Mr Trump’s group benefits materially from his spell in office, any doubt over whether policies are crafted with the American people in mind or his own bottom line is corrosive.

Source: economist

How Donald Trump is monetising his presidency