IN MOST four-decade-old firms run by greying co-founders, investors would have long since demanded clarity on succession. But private equity works differently: the industry has been dominated by its pioneers ever since its origins in the 1970s. So an announcement on July 17th about its future leadership by KKR, one of the world’s largest private-equity firms, puts it a step ahead of its rivals. Its aim of ensuring that the firm has the right structure in place “for decades to come” is not obviously shared across the industry.

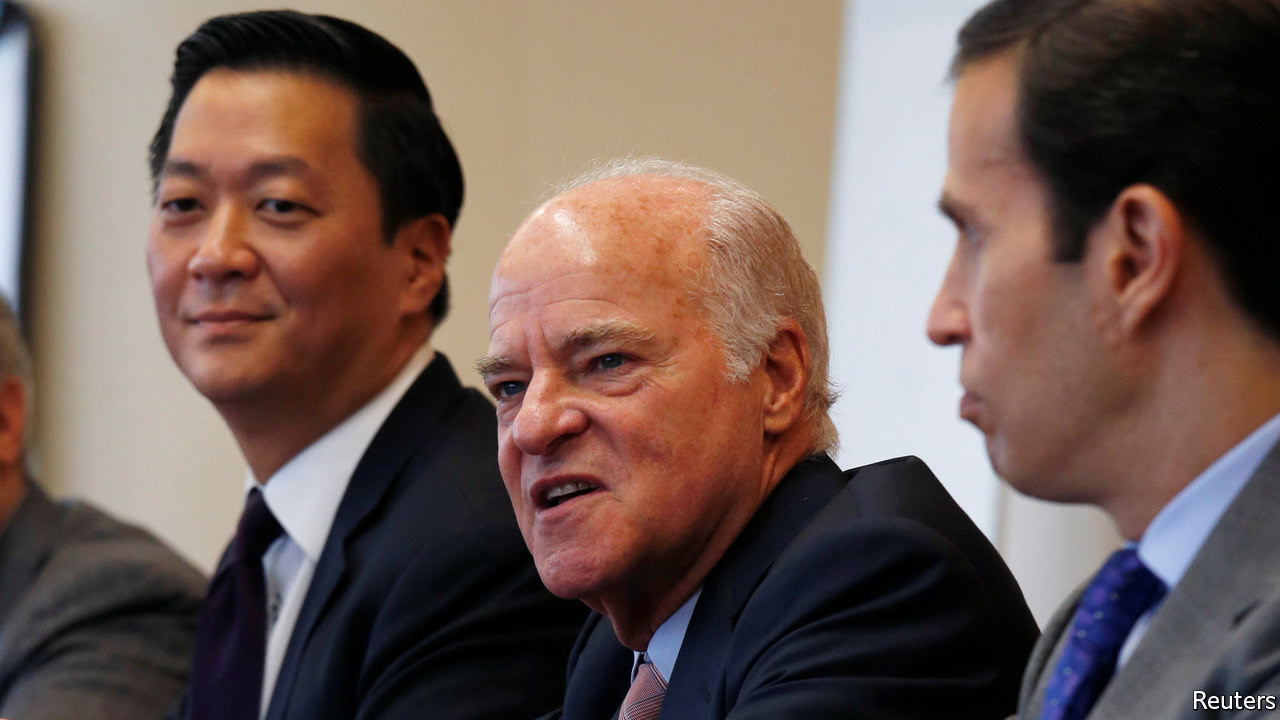

KKR has been run since 1976 by two of its founders, Henry Kravis and George Roberts (both in their early 70s). They are staying on as co-chairmen and co-chief executives but with less of a day-to-day role. Lining up behind them are a pair of 40-somethings, Joe Bae and Scott Nuttall, who will join the board and take the titles of co-president and co-chief operating officer.

-

Jim Henson, master of puppets

-

Can Donald Trump pardon himself?

-

How Poland’s government is weakening democracy

-

A chance finding may lead to a treatment for multiple sclerosis

-

What is the moral compass of “Game of Thrones”?

-

Violence and diplomatic upheaval over the al-Aqsa mosque

Such explicit, public succession planning is unusual. Stephen Schwarzman, the boss and co-founder of Blackstone, the world’s largest private-equity firm, has hinted that Jonathan Gray, head of its property arm, could succeed him. But the chiefs of other behemoths, such as Leon Black of Apollo, or David Rubenstein, William Conway and Daniel D’Aniello, the trio behind and atop Carlyle, have largely kept silent about their heirs. So too have the bosses of many smaller firms.

Public reticence does not necessarily imply a lack of planning. Most private-equity firms are private partnerships and do not face the level of scrutiny accorded to publicly listed firms like KKR. But there is often pressure to reveal succession plans from investors who are committing capital that could be tied up for ten years or more.

Not having a scheme for a smooth transition of power carries risk in all businesses. But the potential for acrimonious disputes, not least over money, is particularly high in private equity. In a recent analysis of over 700 firms, Josh Lerner and Victoria Ivashina of Harvard Business School found that compensation of partners in the industry was inextricably tied, not to individual investment success, but rather to whether they were there at a firm’s birth. The average founder receives nearly 20% of all profits from “carried interest” and owns a 31% stake in his firm; a non-founding senior partner gets on average only 11% of profits and owns less than 14% of the firm.

Such unequal arrangements can make a transition trickier. Reallocating profits or transferring outsize ownership stakes to other partners risks internal bickering. In 2010 Justin Wender, the anointed successor of John Castle, the founder of an American firm called Castle Harlan, left amid a dispute about “future ownership”. Friction over succession and profit-sharing at Charterhouse, a British firm, came to light in 2014 in the form of a lawsuit by a disgruntled former partner, who alleged, among other things, that the firm tried to force him to sell his stake at an excessively low price. Charterhouse won the case.

Mr Lerner worries that a growing trend of exiting founders selling their stakes externally causes other problems, particularly for private firms. If such firms are no longer in the hands of those who make the profits, for example, that may weaken the alignment of interests that has driven much of the industry’s success.

All these concerns will come to a head when increasing numbers of founders step back. Large firms like KKR have diverse businesses and big teams of executives; smaller counterparts, where power is concentrated with individual founders, may have more trouble adjusting. All the more reason to follow KKR’s lead on leadership. Success and succession will become ever more intertwined.

Source: economist

KKR, a private-equity giant, lays out its succession plan