THE modern pharmaceutical firm lives or dies on the strength of its drug portfolio. As patents expire on lucrative medicines, they must replace the income that has been lost by inventing new drugs, or buying them in from outside. Both paths are expensive. But the costs of failure are greater, and this is how it was possible for a large and successful firm—such as British-based AstraZeneca—to shed 15% of its market value in a single day last week. Around £10bn ($13.2bn) was lost on news of disappointing results in one of its clinical trials (its shares have since rebounded by 4%).

The trial was to find out if a pair of drugs would treat a form of lung cancer. The drug, Imfinzi, and the experimental drug tremelimumab, belong to a new category of immunotherapy medicines called “checkpoint inhibitors”. Similar drugs are made by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), by Merck in America and Roche, a Swiss firm. In an interim finding, it was reported that Astra’s combination did not offer an improvement over therapies already on the market. John Rountree, a partner with Novasecta, a consultancy, says the results suggest it is still early days for immuno-oncology R&D, not that there is something wrong with the technology. Last year, BMS lost 16% of its market value after a failed trial of Opdivo, another checkpoint inhibitor, in lung cancer.

-

Investors prefer airlines with good customer service

-

Immigrants do not need to speak English before they arrive

-

Unproductive entrepreneurship is increasingly common in America

-

Dinosaurs used the same tricks to hide as modern animals do

-

Sam Shepard’s terrifying, hilarious rage

-

The mystery of high unemployment rates for black Americans

The promise of these drugs means the market has become crowded. It is harder for later entrants such as AstraZeneca, whose drug Imfinzi is the fifth checkpoint inhibitor that came to market, but it has a wide portfolio of good immuno-oncology drugs, which means it can offer these in combinations—something that is expected to offer a therapeutic benefit to patients.

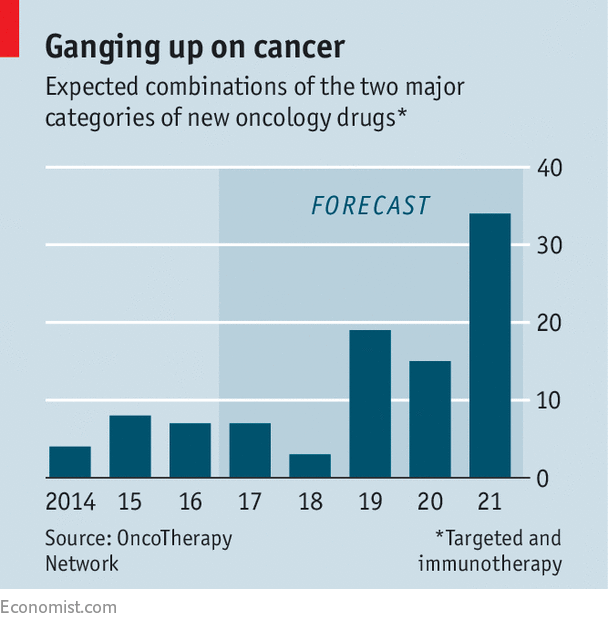

Yet as the number of checkpoint inhibitors and immunotherapy drugs rises, the number of such potential combinations of treatments is growing (see chart), which could mean many expensive clinical trials for pharma companies. They must decide how to obtain the best sets of drugs. Mergers and acquisitions to get the right treatments look expensive (research from Novasecta found that last year the median price of a pharma firm was 39 times its revenue, compared with 19 times in 2015 and 8 times in 2014).

Instead, pharma firms that have competed fiercely for decades have decided that sometimes it is better to co-operate. Last week, Merck bought half the rights to AstraZeneca’s Lynparza in a deal worth $8.5bn. The firms will co-develop and sell a drug known as a “PARP inhibitor”. It will be developed in combination with checkpoint inhibitors made by both firms. In January this year Merck also expanded its existing collaboration with Eli Lilly to study how the drug Lartruvo, a targeted cancer drug, acts with Merck’s Keytruda. On July 25th Eli Lilly said it will out-license or co-develop one-third of its oncology pipeline. There are many more examples.

The industry is convinced that collaboration is needed in immuno-oncology, reckons McKinsey, a consulting firm. Working together is an effective way to mix laboratory talent and to bring medicines to patients, adds Mr Rountree. It is evidence of this drive to find combinations of drugs that most of the hundreds of trials of the top two checkpoint inhibitors on the market are led by firms or institutions other than the company that actually owns the drug, says McKinsey.

If the collaborations turn out to work, the industry will have advanced in two important ways. First, it would mean that pharma has found a way to create value for its shareholders aside from the expensive and unpredictable route of M&A. Second, the deals could drive efficiency in an industry that is struggling with productivity. Studies show that pharma productivity (measured by the number of new molecular entities created per billion dollars of investment) has been declining for most of the industry’s history. There is no denying that the deals are complex to arrange, legally speaking, but being awkward frenemies could be worth it.

Source: economist

A rush for immunotherapy cancer drugs means new bedfellows