THE private-equity business presents a paradox. Its barons like to boast of revamping the companies they buy. But they themselves have been steadfast to their own business model, centred on funds with a ten-year life. Within this time span, fund managers, known as “general partners” (GPs), commit to buy, manage and sell a clutch of companies; investors commit to lock up their money for the duration. Sometimes GPs or investors chafe at the time constraint. A new segment of the secondary market, “GP-led” deals, has sprung up to help them.

Investors wanting to exit a fund early need to find a buyer for their stake in the secondary market. But sometimes none will offer an attractive price. Sometimes also, a fund nearing its expiry date may find itself still holding a large number of its investments. GP-led deals place the onus on fund managers to find buyers.

-

Why so many African presidents are ditching term limits

-

Investors prefer airlines with good customer service

-

Immigrants do not need to speak English before they arrive

-

Unproductive entrepreneurship is increasingly common in America

-

Dinosaurs used the same tricks to hide as modern animals do

-

Sam Shepard’s terrifying, hilarious rage

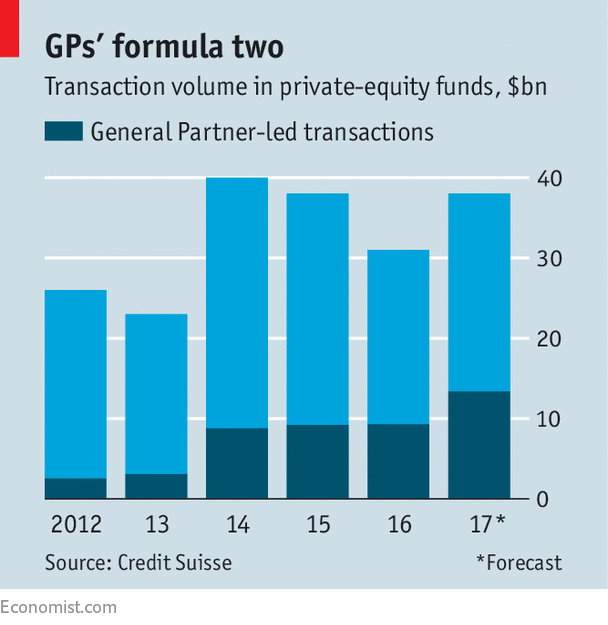

Such transactions have quickly grown from just 10% of the secondary market in 2012 to over one-third this year, according to estimates from Credit Suisse, a bank (see chart). Some such deals offer liquidity to investors during a fund’s “normal” lifetime. For instance, when many investors want to sell out of a fund early, a manager may solicit offers from buyers through a tender process, often getting investors a better price, as in a 2015 deal by Palamon Capital Partners, a British firm. A variant is a “stapled” deal where a firm ties a secondary-market sale to a primary fundraising. In June, Lexington, a secondary investor, bought out €1.2bn ($1.4bn) from investors in a 2012 fund of BC Partners, a London-based firm, while committing €600m to that firm’s newest fund.

Perhaps the greatest novelty of GP-led deals, however, has been to ease the ten-year straitjacket. Private-equity managers often reckon they could make a better return by holding some assets for longer. But investors usually want their money back as promised, and are reluctant to stick around for much more than an additional year or two. GP-led fund restructurings and spin-outs try to close this gap.

The restructuring market had a rocky start in around 2011. Some of the earliest deals involved poorly performing managers with no plans to set up any new funds. Investors were understandably unhappy at being stuck in “zombie funds”, or even being asked to chip in more.

But as the market has grown, restructuring and spin-out deals have become a way to provide investors with the liquidity they want, while allowing assets to be managed for longer. The deals now nearly always involve new capital, usually from specialist investors in the private-equity secondary market, such as HarbourVest or Neuberger Berman. So existing investors can be offered choices ranging from cashing out to staying put to investing more.

Such deals are not necessarily just for strugglers, but have become a tool for fund managers to pursue other goals. For instance, Investindustrial, a firm focused on southern Europe, in March 2017 put some assets into a new fund, largely because it expected better returns from managing its prize asset, PortAventura, a Spanish theme park, for longer. In 2016, Bridgepoint, a British private-equity firm, sold several smaller firms from its 2005 fund to a new fund, as it wanted to focus its efforts on a few investments, such as its crown jewel, Pret A Manger, a sandwich chain, which it wished to take public.

The recent boom has been in part cyclical. In private equity’s core markets of Europe and America, where investors expect continued growth, secondary stakes are selling on average at just a 5% discount to their net asset value, making restructurings look attractive. In South America, by contrast, where the economic outlook is cloudier, the going discount is about 30%, and negotiations over several GP-led restructurings have collapsed.

David Atterbury of HarbourVest, however, argues that GP-led deals are far from a temporary phenomenon: investors prize the liquidity they bring, and managers appreciate the newfound flexibility. Credit Suisse reckons private-equity secondary transactions may approach $40bn this year. But according to Preqin, a data provider, private-equity assets stood at nearly $2.6trn worldwide at the end of 2016. The new market has plenty of room to grow.

Source: economist

The private-equity business learns to be more flexible