WHEN Heathrow airport opened, in 1946, the only retail facilities were a bar with chintz armchairs and a small newsagent’s. The first terminal was a tent, a far cry from the four halls, resembling vast shopping malls, at the London airport today. Retail spending per passenger is the highest of any airport. This summer’s consumer crazes include Harry Potter wands and cactus-shaped lilos.

Heathrow’s journey from waiting room to retail paradise is the story of many airports. Before the 1980s, most income came from airlines’ landing and passenger-handling charges. Then “non-aeronautical” revenue—from shops, airport parking, car rental and so on—rose to around two-fifths of their revenues, of $152bn worldwide in 2015. But amid signs that non-aeronautical income is peaking, especially in mature aviation markets such as North America and Europe, the industry fears for its business model.

-

The ACLU stands up for an alt-right author’s freedom of speech

-

Ryanair drops plans to serve Ukraine

-

British university rankings

-

British university rankings methodology

-

“A Ghost Story” is an enigmatic look at loss

-

How Donald Trump may be making life easier for one violent street gang

When airports were state-owned, and run not for profit but for the benefit of the local flag-carrier, such ancillary income was less important. Airports in Asia, Africa and the Middle East still operate like this. Globally, two-thirds lose money; the share is 75% in China and 90% in India. But most airports in Europe and the Americas have to pay their own way.

Britain led the way with privatisation in the 1980s. Canada leased its major airports to private-sector entities in 1994, and is now considering whether to sell them completely. Squeezed state budgets in America mean that most publicly owned airports are managed by arms-length organisations that must break even. And a wave of privatisation is sweeping Europe, where nearly half of terminal capacity is now owned by the private sector. France’s main airports in Paris are still partly in state hands, but Emmanuel Macron, the president, aims to sell the rest. Latin American countries are following closely behind.

Their timing may be off. Although passenger numbers are still booming—growing worldwide by 6.3% last year, according to IATA, an airline-industry group—non-aeronautical revenues per person are falling across North America and Europe, a trend that is offsetting some of the rise in aeronautical revenues from higher passenger numbers.

On the retail side, some temporary factors are at work, such as a crackdown on corruption by Xi Jinping, China’s president, which has crimped sales of luxury items to high-spending Chinese. Extra security checks introduced after a run of terror attacks have cut passengers’ shopping time, and that may change in future.

Yet there are structural causes too. Tyler Brûlé, an airport-design guru and editor-in-chief of Monocle, a British magazine, notes that the duplication of nearly identical duty-free and luxury-goods outlets at airports across the world has left many passengers unexcited by the range of items on offer. The demographics of regular flyers, which have shifted towards people with less money to spare, have not helped. At the start of the year, Aéroports de Paris, Frankfurt airport and Schiphol airport, in Amsterdam, announced drops in spending per passenger in 2016 of around 4-8%.

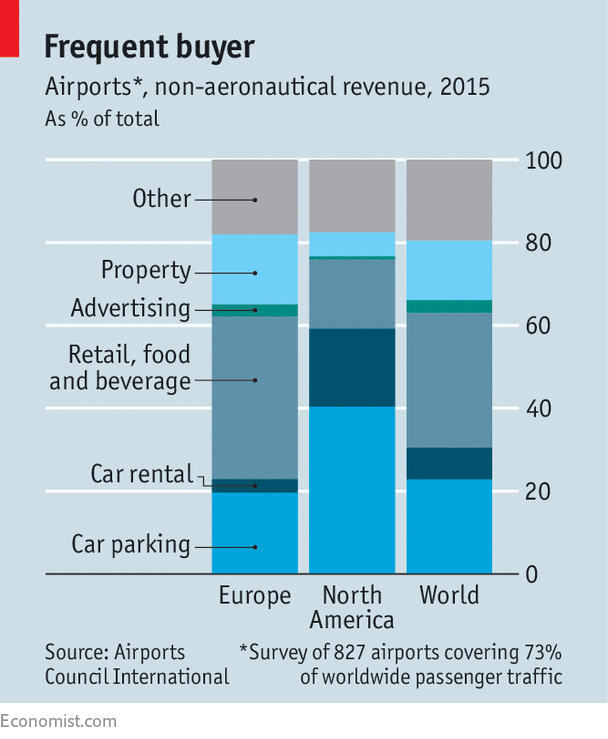

Under even greater threat, especially in North America, is income from car parks, which makes up two-fifths of non-aeronautical revenues across the continent, and car-rental concessions, which brings in a further one-fifth. At European airports the shares are 20% and 3% respectively (see chart). These businesses are being disrupted by ride-hailing apps, mainly Uber and Lyft, which make travel by taxi more affordable compared with renting or parking a car at the airport. In the past year, revenues from parking have fallen short of forecast budgets by up to a tenth, airport managers say, and next year they expect worse results. Many airports at first tried to ban Uber’s and Lyft’s cars from their taxi ranks, but drivers found a way round it, in some cases picking up rides from nearby houses. Now more are allowing Uber and Lyft to use their facilities.

The likely direction of new technology and environmental regulation will continue to sap revenue from parking and car hire, reckons Francois-Xavier Delenclos of BCG, a consultancy. Because airports must meet local air-pollution targets, they will discourage passengers from using cars with internal combustion engines. Heathrow, for instance, wants the share of passengers using public transport to reach the airport to increase from 41% to 55% by 2040; many American airports have similar targets. Even the adoption of electric self-driving cars will offer little respite. After dropping off passengers, they will be able to take themselves home.

Revenues are stagnating just when airports in America and Europe need more cash to expand, to cope with demand for flights. Without expansion beyond current plans, by 2035, 19 of Europe’s biggest airports will be as congested as Heathrow today, which operates at full capacity, according to Olivier Jankovec, director-general of ACI Europe, a trade group in Brussels. In America the Federal Aviation Administration, a regulator, estimates that congestion and delays at the country’s airports cost the economy $22bn in 2012. This will rise to $34bn in 2020 and $63bn by 2040 if capacity is not increased. Meanwhile, the cost of airport construction is rising more than twice as fast as general inflation, mainly due to rising costs of specialised labour.

For those tramping through airports, this is bad news. Without space for extra airlines, established carriers can raise their fares without fear of new competitors moving in. Neither are incumbent airlines keen to foot the bill for expansion. IAG, an Anglo-Spanish group, is fighting plans to levy higher landing fees on its airlines, including British Airways, to pay for new runways at Heathrow and in Dublin. Expect to see more battles like this, for lilos and duty-free Smirnoff vodka cannot pay for all the terminals and runways that America and Europe need.

Source: economist

Airline profits: ready to depart