FINANCIAL markets are supposed to be the font of all wisdom, weighing up the information available and condensing it into a set of prices. Investors are presumed to have an insight into the future—falling bond yields are seen as a sign that the economy is slowing, for example.

But are investors that clever when it comes to politics? Gambling markets show how they assess political risk. They expected the Remain campaign to win the Brexit referendum and Hillary Clinton to become America’s president, and were proved wrong. Indeed, on Brexit, the mass of gamblers (the general public, in other words) backed Leave, but the odds were skewed by some wealthy punters who favoured Remain. Those rich gamblers were probably people who trade in financial markets; the plunge in the pound after the result suggests that most investors were caught on the hop.

-

The ACLU stands up for an alt-right author’s freedom of speech

-

Ryanair drops plans to serve Ukraine

-

British university rankings

-

British university rankings methodology

-

“A Ghost Story” is an enigmatic look at loss

-

How Donald Trump may be making life easier for one violent street gang

Before the presidential election, most people on Wall Street to whom Buttonwood spoke thought that a victory for Donald Trump would be bad for the markets. But as the results came in, there was a sudden change of tone and both the dollar and equities rallied.

With the American stockmarket repeatedly reaching new highs (as Mr Trump is fond of pointing out), it may look as if this post-election mood change was prescient. But not really. The rationale for the “Trump bump” was that the administration would quickly pass a stimulus package in the form of tax cuts and infrastructure spending. This would cause economic growth to accelerate (good for equities); in turn, this would prompt the Federal Reserve to push up interest rates (good for the dollar).

But the stimulus plan has yet to be put in place, and is nowhere near passing Congress. American GDP grew by around 0.3% in the first quarter and just over 0.6% in the second; the more recent figure is not bad, but only in line with the euro zone’s growth in the same period. In June the IMF trimmed its forecast for American growth in 2017 to 2.1%, and predicted the same figure for 2018.

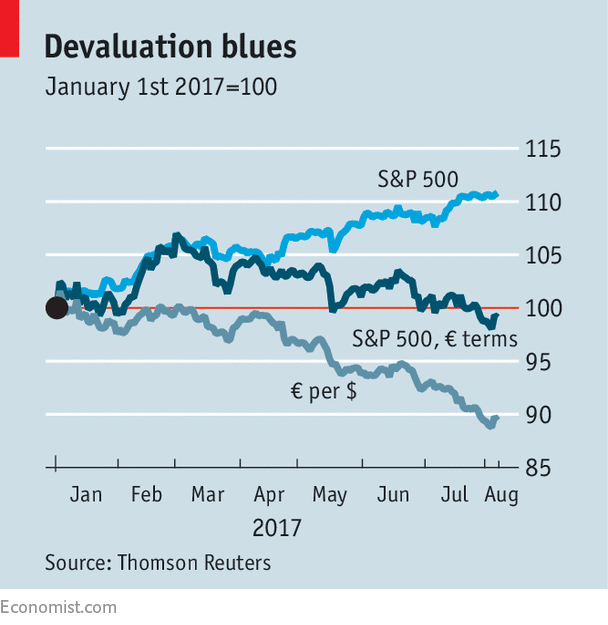

The result is that the dollar has been losing ground against the euro for much of the year, and is now lower than before Mr Trump took office. That is not just because of events in America, of course: the euro zone has seen growth pick up and political risk decline since Emmanuel Macron was elected president of France.

This currency shift puts the stockmarket rally in context. In dollar terms, euro-zone equities have easily outperformed Wall Street this year. Or, to put it another way, in euro terms American equities have fallen (see chart).

American investors won’t mind about that; they are still enjoying strong gains. But some of those returns are the result of a weaker currency, which means that the foreign earnings of multinationals are worth more in dollars. And the strongest-performing sector of the year has been technology, which tends to benefit from global, rather than purely domestic, growth. The yield on the ten-year Treasury bond is lower than it was at the start of the year—a sign that hopes of faster growth have cooled. In short, the stockmarket may be up, but not for the reasons that investors had expected.

Furthermore, it seemed even at the start of the year that investors were naively optimistic about the administration’s agenda. As a candidate, Mr Trump did not have a very detailed economic plan, nor the range of high-powered advisers that most nominees tend to accumulate. As well as promising to cut taxes, he also threatened to introduce protectionist policies directed against Mexico, China and other countries. If those policies had been pushed through (and they may still be), the stockmarket would have taken a severe hit.

It may be that, when it comes to politics, wishful thinking plays a large part for investors. Brexit creates risks for financial companies that are based in London, so it was tempting for those involved to think that it would not happen. The Republican agenda promised tax cuts for the better-off in America, as well as financial deregulation. Both would be good news for the denizens of Wall Street, so it is not surprising that they hoped their dreams would come true.

But it is a mistake to think that investors know something about politics that everyone else does not. Before elections, they must simply rely on the opinion polls. And analysing corporate balance-sheets is a lot easier than making sense of the policy pronouncements of elected officials—especially when a leader is as unpredictable as Mr Trump.

Source: economist

Investors are not great at predicting politics