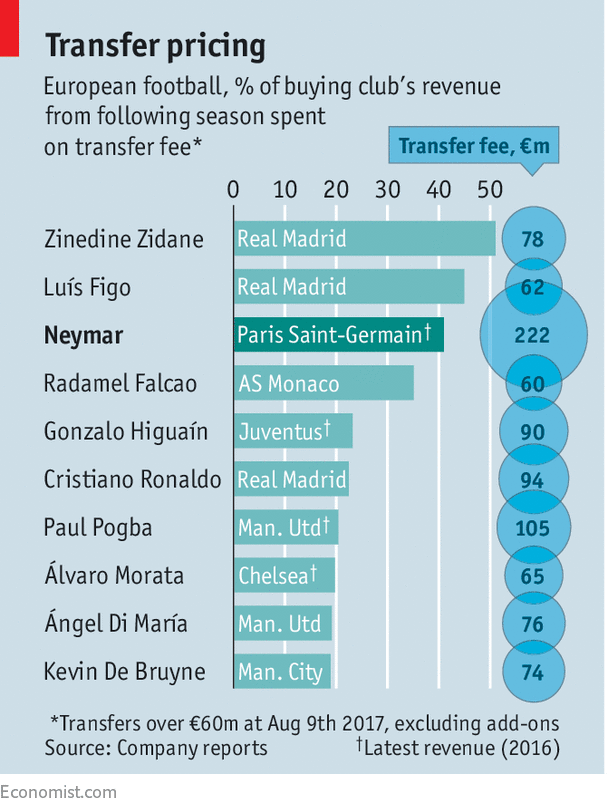

FOR football clubs, August is often the costliest month, when they make vast bids for each other’s players. This year has been particularly lavish. On August 3rd Paris Saint-Germain (PSG), a French team, signed Neymar da Silva Santos Júnior, a Brazilian forward, from Barcelona for €222m ($264m), more than double the previous record price for a footballer.

With three weeks of the transfer “window” left, teams in Europe’s “big five” leagues—the top divisions in England, Spain, Germany, Italy and France—have paid €3.2bn, just short of the record of €3.4bn set last year. The €179m splurged by Manchester City, an English club, on defenders outstrips 47 countries’ defence budgets. Arsène Wenger, a veteran manager of Arsenal, a London team, and an economics graduate, describes the modern transfer market as “beyond calculation and beyond rationality”.

-

The ACLU stands up for an alt-right author’s freedom of speech

-

Ryanair drops plans to serve Ukraine

-

British university rankings

-

British university rankings methodology

-

“A Ghost Story” is an enigmatic look at loss

-

How Donald Trump may be making life easier for one violent street gang

Neymar, as he is known, will cost PSG’s owners, a branch of Qatar’s sovereign-wealth fund, about €500m over five years. In the betting markets, his arrival has boosted PSG’s implied chances of winning the Champions League, Europe’s most coveted club competition—but only from around 5.5% to about 9%. And prize money and ticket sales alone struggle to generate enough revenue to recoup such an outlay.

That does not make Neymar a bad investment. The goals he scores may matter less than the gloss he lends to the club’s brand and the sponsors he will lure. He earns more from endorsements than any footballer except Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi. Some 59% of PSG’s revenue of €520m last year was commercial (ie, other than ticket sales and broadcasting fees), more than any other club in the big five leagues. Neymar has more followers on Instagram, a social network, than does Nike, his main sponsor and the provider of PSG’s kit, for which privilege it pays €24m a year. Neymar’s popularity will help PSG when this deal is renegotiated. Nike has already agreed to pay Barcelona €155m a season from 2018.

PSG’s owners are confident of breaking even, though they could afford a loss. Qatar has been spending €420m a week preparing for the 2022 World Cup, and the signing of Neymar is a message that the otherwise embattled country remains strong and rich. The danger is to PSG, since under “financial fair play” rules, teams are punished if they fail to limit their losses. In 2014 the club was fined for violating these. Another failure to balance the books could mean a ban from the Champions League.

Such spending caps irk billionaire owners, but they have helped prevent the inflation of a transfer-fee bubble. The rapid rise is a result of European football’s expanding fan base. In the English Premier League, football’s richest, average net spending on players per club has stayed roughly constant, hovering at around 15% of revenue since the 1990s, according to the 21st Club, a football consultancy.

As long as clubs’ revenues keep growing, the transfer boom is likely to persist. Broadcasting revenue, the game’s first big injection of cash in the 1990s, has become, in the internet era, the weakest link. British television audiences for live games have dipped as some fans opt for illegal streaming sites or free highlights. Zach Fuller, a media analyst, reckons that signing a sponsorship magnet like Neymar is a hedge against volatility in that market.

Audiences are more robust elsewhere: around 100m Chinese viewers tune into the biggest games. Manchester United are the most popular team on Chinese social media, despite qualifying for the Champions League only twice in the past four seasons. They have overtaken Real Madrid, who have won the trophy three times in the same period, as the world’s most prosperous club. If Neymar unlocks new markets as well as defences, then PSG may have backed a winner.

Source: economist

Why the world’s best footballers are cheaper than they seem