QIN SHIHUANG was the emperor who first unified China, through bloody conquest more than two millennia ago. Known for starting the Great Wall and burying scholars alive, he has a new claim to fame: the central bank has drawn on his construction of a national road system to help explain its new monetary system. In a report on August 11th, the People’s Bank of China seized on an idiom derived from his road-building experience: it had “shaved off mountain peaks and filled valleys” in managing liquidity.

The modernisation of monetary policy is in its own way a monumental project for China. Over the past two decades, the central bank’s conduct of policy had two defining features. It focused on the quantity, not the price, of money. And it relied on inflows of foreign cash to generate new money. Both features are now slowly changing, bringing China closer to the norm in developed markets, an essential transition for an increasingly complex economy.

-

Robert Pattinson has put his teen heartthrob roles behind him

-

Steve Bannon is ousted as the president’s chief strategist

-

Islamist terrorism in Catalonia leaves the Spanish wondering why

-

A year on from Brexit

-

The misplaced arguments against Black Lives Matter

-

Donald Trump blusters, Latin America shrugs

Start with interest rates. These used to be of secondary importance in China. Regulators instead used quotas to dictate how much banks lent and in effect fixed their deposit and lending rates. This made sense when China was in the early stages of moving away from a planned economy. Crude targets were still needed. But as a bigger, rowdier financial system took shape, these targets became less relevant. With the emergence of a large bond market, myriad non-bank lenders and new investment options for savers, banks now face more competition for deposits and in building up their loan books.

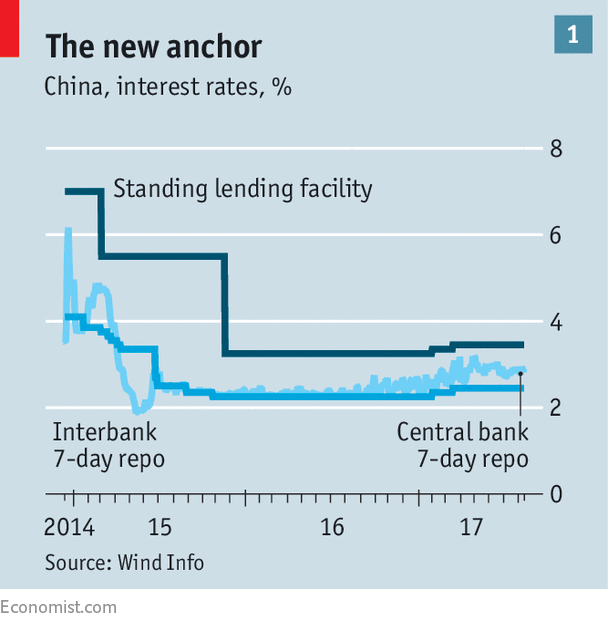

Seeing this, the central bank in late 2015 gave banks freedom, in theory, to set their own lending and deposit rates. It also eliminated mandatory loan-to-deposit ratios and put less stress on credit quotas. However, this opened a gap. It had relinquished its former controls without new ones in place. The answer has been to create a policy rate, much like benchmark short-term interest rates in America and Europe. The central bank has tried to create an equivalent anchor in China’s financial system: the seven-day “repo” rate (the bond-repurchase rate at which it lends to banks).

To do so it has established a band around the seven-day rate, with a lower bound for lending to banks flush with cash and an upper bound for those in need. To cap rates at the upper bound, the central bank also started accepting a wider array of collateral. Since mid-2015 this has worked. The central bank has kept the seven-day rate within the corridor and nudged it up as the economy has gathered pace (see chart 1). On August 15th, in its annual review of China’s economy, the IMF passed a tentative verdict: “The conduct of monetary policy increasingly resembles a standard interest-rate-based framework.”

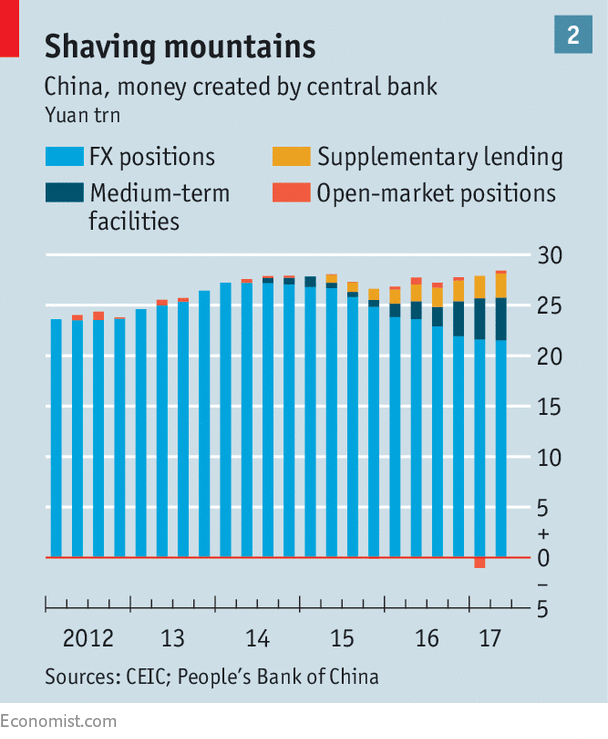

Complementing this shift has been the central bank’s creation of a range of liquidity-management tools. Since 2013 it has opened a baffling plethora of new lending windows: short-term liquidity operations, standing lending facilities, medium-term lending facilities and pledged supplementary lending. All added up to the same thing: conduits to inject cash at different rates and for different durations or, by letting them expire, to withdraw cash.

Their importance has been clear over the past two years as capital outflows eroded the value of China’s foreign-exchange reserves. This placed pressure on domestic liquidity, since China had relied on cash inflows to generate money growth (issuing new yuan to buy up the dollars streaming in). After initial hiccups, the central bank more than made up for the loss of dollars at home by using its various tools (see chart 2). As a result, it has been better able to manage cash levels on a daily basis. High volatility in money-market rates, once a regular occurrence, has all but vanished, hence the central bank’s conceit that, in a Qin-like manner, it has shaved off mountain peaks and filled valleys.

Nevertheless, both policy shifts are works in progress. With state-owned banks and companies still counting on government support in the event of trouble, interest rates have less signalling value than in a freer market. The central bank, for its part, continues to use administrative controls to influence lenders. And its success in managing liquidity has been greatly helped by China’s tightened grip on its capital account over the past year. Without that, money growth at home might have fuelled more capital outflows. It is, in other words, a gradual approach to reform, in which sense the invocation of China’s first emperor is unfortunate. His rule was transformative but violent and short-lived. Slower monetary-policy shifts, in contrast, have much to recommend them.

Source: economist

China modernises its monetary policy