WHEN America’s unemployment was last as low as it has been recently, in early 2007, wages were growing by about 3.5% a year. Today wage growth seems stuck at about 2.5%. This puzzles economists. Some say the labour market is less healthy than the jobless rate suggests; others point to weak productivity growth or low inflation expectations. The latest idea is to blame retiring baby-boomers.

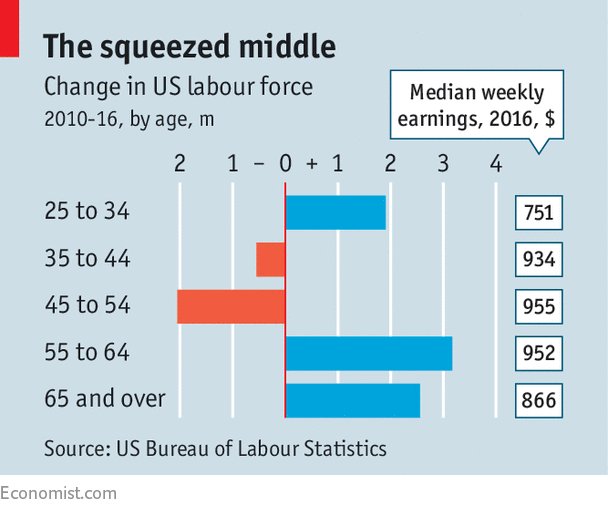

The thinking goes as follows. The average worker gains skills and seniority, and hence higher pay, over time. When he retires, his high-paying job will vanish unless a similarly-seasoned worker is waiting in the wings. A flurry of retirements could therefore put downward pressure on average wages, however well the economy does. The first baby-boomers began to hit retirement age around 2007, just as the financial crisis started. And since 2010, the first full year of the recovery, the number of middle-aged workers has shrunk considerably. They have been replaced partly by lower-earning youngsters (see chart).

-

Migration to Britain is falling

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

How America botches executions using lethal injections

-

How hip-hop is introducing children to coding and technology

-

Foreign reserves

-

Why Roger Taney’s statue was removed from Maryland’s state house

Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco think this could explain disappointing wage growth over that period. They split earnings growth into the portion caused by pay rises, and the portion caused by people joining or leaving the workforce. From mid-2012 until recently, changes to labour-force composition have reduced income growth by about two percentage points. By comparison, in early 2007 the drag was less than one percentage point. For those in work continuously, pay is rising just as fast as it was then.

Does that mean the labour market is running hot? Not so fast, says Adam Ozimek of Moody’s Analytics. He points out that the number of workers aged over 55 is growing, not shrinking, as a fraction of the workforce. What is more, statistically controlling for ageing barely changes estimates of aggregate wage growth, according to his model.

So what is going on? The San Francisco Fed’s researchers also note that many low earners have recently joined the labour force (such workers are usually the last to benefit from economic expansions). Growth in low-skilled jobs can hold back average wage growth. But this explanation does not imply that the labour market has fully recovered, because more people may yet be tempted to look for a job. In fact, Mr Ozimek denies there is a wage puzzle to begin with. Replace the unemployment rate, which counts only those who are seeking work, with the fraction of 25-to-54-year-olds who are jobless, and wage growth is exactly where you would expect it to be (at least according to Mr Ozimek’s preferred measure of pay and benefits).

Another problem with the ageing explanation is that it is not just wage growth that has been disappointing. Inflation, too, has been puzzlingly low this year: the core consumer-price index, which excludes food and energy, has undershot forecasts for five consecutive months. Ageing cannot easily explain low inflation. True, retiring baby-boomers reduce firms’ wage bills. But if older workers earn their high pay through high productivity then firms’ unit costs should not fall as retirements rise.

Ageing is too often overlooked as an explanation for economic trends—politicians routinely promise that the economy will grow as fast as it did before baby-boomers started retiring and the workforce began to shrink. Yet when it comes to wage growth, the effect of ageing is probably modest. Policymakers should not hide behind it. Despite low unemployment, the labour market is not yet simmering.

Source: economist

Does ageing explain America’s disappointing wage growth?