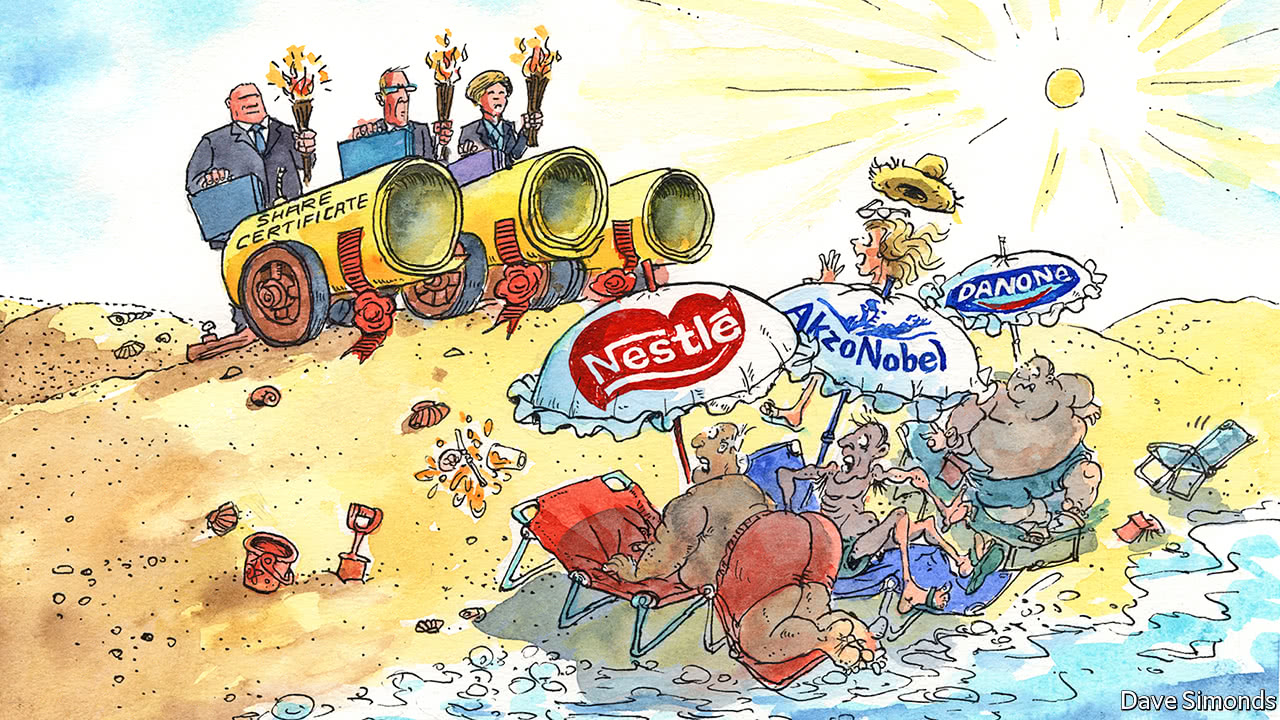

LEAVE it to the Americans to besiege European companies in August, when the entire continent is on holiday. It emerged this month that Corvex Management, an American hedge fund, had built up a $400m position in Danone, a French food giant. AkzoNobel, a Dutch paints-and-chemicals firm which has been under heavy fire from Elliott Advisors, a subsidiary of another American activist fund, agreed to appoint three new directors to its board. An even bigger skirmish is under way in Switzerland, where Third Point, an American fund run by Daniel Loeb, is seeking to shake up Nestlé, the world’s biggest food company. Ulf Mark Schneider, Nestlé’s new boss, is under pressure to present bold plans to investors in September.

Such tussles used to be relatively rare in Europe. But shareholder activism is on the rise, with restive investors demanding corporate overhauls. Armand Grumberg, a mergers lawyer in Paris, last year counted 70 such campaigns in continental Europe. He expects this year to be even livelier. “It is the new normal,” he says.

-

Samsung’s boss is sentenced to prison

-

Courts repeatedly chastise Texas for voting-rights violations

-

Thailand’s former prime minister, Yingluck Shinawatra, may have fled

-

Appalling behaviour on London’s Tube

-

Construction’s productivity puzzle

-

The Vatican’s secretary of state visits Moscow for the first time in 19 years

The surge in activism has several causes. As American activist funds jostle to find targets at home, some are seeking less well-trodden hunting grounds abroad. Relatively cheap European firms are tempting prey. Many Americans also see continental models of corporate governance as ripe for disruption. Americans (and Britons) think that boards must prioritise shareholders’ interests; Europeans, backed by courts, insist boards should also take the interests of staff, creditors and suppliers into account.

It is not just Americans who have sprung into action. A London-based group, The Children’s Investment Fund, recently led a successful campaign to urge Safran, a French maker of aeronautical parts, to lower its offer price for Zodiac, a poorly run French producer of aeroplane seats and toilets. On the other side of the deal, a French fund called CIAM had invested in Zodiac and sought the Safran takeover.

CIAM’s profile has risen in recent years. In 2013 it opposed a sale of Club Med, a tourism company in which it held a stake; that allowed a Chinese buyer, Fosun International, to step in with a higher bid. CIAM also campaigned for Disney to pay more to minority investors in Euro Disney, a subsidiary that was taken private in June. Anne-Sophie d’Andlau of CIAM calls such activism “new in France”, but says the trend is picking up. Activists previously struggled even to meet asset managers, for instance in Paris, says Ms d’Andlau. Now investors listen when she explains an idea.

In Germany a new corporate-governance code, modelled on a British one, is emboldening activists, too: the latest version says that institutional investors “are expected to exercise their ownership rights actively”. Cevian Capital, a big Swedish activist group, has built up a holding in ThyssenKrupp, a German steelmaker. Knight Vinke, yet another active investor, has been trying to dismantle E.ON, a German energy conglomerate. A German-led investment fund, Active Ownership Capital (AOC), last year built a 7% stake in Stada, a maker of generic drugs near Frankfurt, eventually forcing changes to its board, managers and strategy. AOC was vindicated this month: two private-equity firms said on August 18th that they had acquired enough shares to complete a €4.1bn ($4.8bn) takeover of Stada. It will be Europe’s biggest such deal in four years.

Many more campaigns are conducted behind the scenes, as funds work amicably with companies. For instance, the founders of Teleios Capital Partners, a Switzerland-based activist fund, say that in the past three years they have urged shake-ups at about two dozen companies. Of these, only three turned sufficiently adversarial to draw public attention.

Some fights do inevitably spill into the open. When they do, Europeans usually try to avoid the rough-and-tumble approach associated with their American peers; it is crucial not to be seen as “aggressive” or like “cowboy Americans”, sniff local activists. A cautious approach makes it easier to win backing from other investors. Teleios recently set its sights on Kongsberg Automotive, a big, lumbering Norwegian car-parts maker. Founders of Teleios describe being chided at first in Norway, for example by local pension funds, for using methods “that were not how things were done”. By laying out detailed plans for Kongsberg and showing “humility”, they won enough allies to support big changes.

If activists find Europe more fertile ground than they once did, they still face difficulties.In many countries corporate-governance rules remain a thicket. In the Netherlands foundations control some companies and may appoint directors or issue new stock. In Germany two tiers of boards govern firms, so an investor might win a seat on a supervisory board yet find no influence over a management board. In France long-term shareholders can claim double voting rights.

Yet investors familiar with European ways can also benefit from such peculiarities. Kay Bommer of DIRK, a lobby group that represents over 300 listed companies in Germany, says that some clever activists try to exploit differences of opinion between supervisory and management boards of German firms. In France, activists with long-term horizons can make use of double voting rights themselves.

Ms d’Andlau says her fund has no shortage of tempting targets, especially among firms worth €1bn-5bn in Germany, Italy, Spain and Switzerland. AOC sees “around 1,000” possible targets in Germany, Scandinavia and the Benelux countries. European bosses may be on holiday, but they cannot properly relax.

Source: economist

Investor activism is surging in continental Europe