ANGLERS love a record catch. Fish farmers, too. So when a salmon bred and raised near this village at the head of a Norwegian fjord was pulled out of captivity earlier this year weighing a sumo-sized 17kg, it was cause for jubilation. “It was fantastic,” says Einar Wathne, head of aquaculture at Cargill, the world’s biggest food-trading firm. Not only was it produced in 15 months, one-fifth faster than usual, it also looked and tasted good. Mr Wathne’s Norwegian colleagues celebrated by eating it sashimi-style shortly after its slaughter.

Cargill is a company usually associated with big boots rather than waders. America’s largest private company has built a reputation after 152 years of existence as middleman to the world, connecting farmers with buyers of human and animal food everywhere. Through a trading network that spans 70 countries (and that includes scores of ports, terminals, grain and meat-processing plants and cargo ships), it supplies information and finance to farmers, influences what they produce based on the needs of its food-industry customers, and connects the two.

-

Whatever she may say, Theresa May won’t fight the next election

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

The roots of Afghanistan’s tribal tensions

-

Donald Trump’s shutdown threat intrudes on Virginia’s governor race

-

Immigrants boost America’s birth rate

Its purchase of EWOS, a Norwegian fish-food company, in 2015 for $1.5bn was its first big foray into aquaculture. It was the second-biggest acquisition in Cargill’s history. That made it quite a splash for David MacLennan, Cargill’s chief executive since 2013, who took over the company just as a dozen fat years in the agriculture industry had drawn to a close. He is now fishing for future sources of growth.

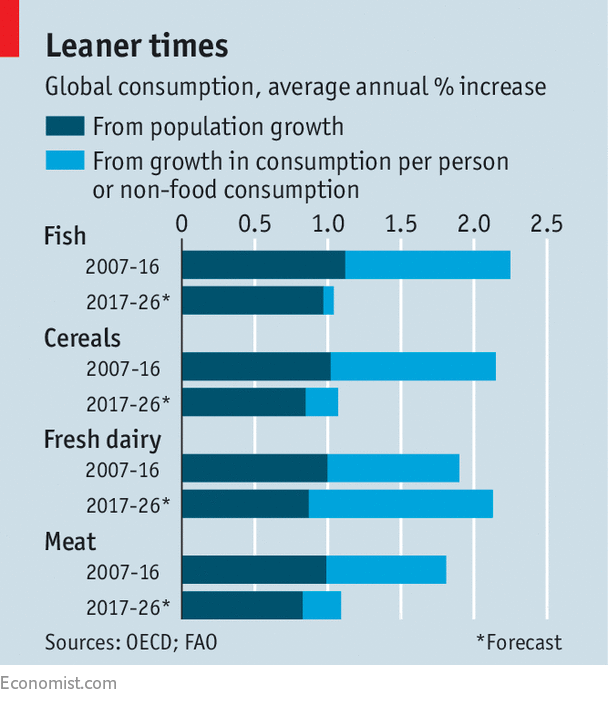

The firm’s foray into the salmon business should help in two ways. First, it is part of Cargill’s attempt to expand into higher-value markets. One of its traditional mainstays, the trading of bulk agricultural commodities, has struggled since the end, in around 2013, of a China-led commodities supercycle. The firm has also suffered from a recent slump in demand for grains for biofuels. Consumption of farmed fish across the world has boomed, meanwhile, partly at the expense of beef, pork and other meats. Fish feed is its highest-cost component, and more efficient ways of feeding are key to the salmon industry’s growth.

Second, Cargill can learn via the salmon-feeding business how to deal with increasingly picky consumers. Mr Wathne notes that salmon is a “premium” product, so consumers want to know not just where it came from, but where what it is fed on comes from. Fishermen of wild salmon, a well-connected bunch, are keen to turn public opinion against the farmed kind. That battle could make Cargill better at handling traceability in more established parts of its food business, such as meats.

Cargill faces a particularly hard task building trust with increasingly information-hungry consumers. To its critics the company epitomises the faceless character of “Big Agriculture”, with boots that trample on the environment, animal welfare, and on small farmers. “I recognise that we are big, and because we are privately owned and because we are primarily business-to-business…it is harder to have that transparency,” says Mr MacLennan. “We want to be more well known.”

Some of his eight predecessors would have spluttered over his idea of more disclosure, which involves wider use of social media, more interviews and more engagement with NGOs. Since generations of Cargill and MacMillan families built the company up from a regional grain trader, born in Iowa in 1865, into a global giant, it has kept out of the limelight, preferring to leave that to the customers whose branded products it provides ingredients for, such as McDonald’s Chicken McNuggets and Danone’s baby formula. Its taste for privacy has not always served it well; the title of a book published in 1995, “Invisible Giant”, sums up Cargill’s sinister reputation in the eyes of anti-globalists. “In the absence of information people will make up their own story,” Mr MacLennan says.

Private ownership has given Cargill room to take a long-term view, but had also enabled management to get away with subpar performance in a business with 150,000 employees and revenues of $110bn. Before Mr MacLennan and his finance chief, Marcel Smits, launched a management reshuffle and streamlined the company in 2015, its weak returns would have been a red rag to an activist investor had it been a public company, says Bill Densmore of Fitch, a ratings agency.

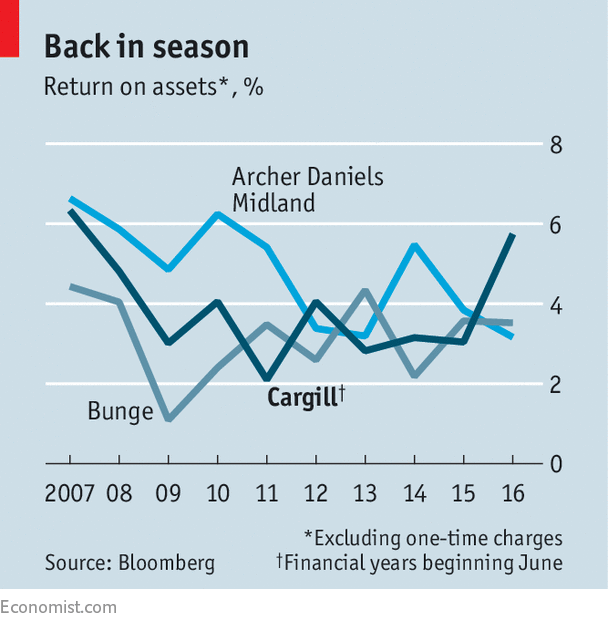

The cost-cutting that has ensued, and a recent upswing in demand for American meat that particularly favoured Cargill, has pushed returns higher than those of its main listed rivals, Archer Daniels Midland and Bunge (see chart ). Yet Craig Pirrong, an expert on trading companies at the University of Houston, says private ownership constrains Cargill’s ability to raise capital to invest in fixed assets as it expands and moves upmarket. Mr MacLennan says he has sought since 2013 to introduce “a bit of more of a public-company culture”. He stresses, though, that there is “no intention of going public”.

The big traders largely squandered the commodities boom of the past decade. Returns languished despite an unprecedented surge in demand for agricultural products, such as cereals, chicken and fish. In that time, Mr MacLennan says, farmers invested in new soil-mapping technologies to improve yields, better seeds and more storage facilities. An ability to hold on to grain until market conditions are favourable has given farmers clout in their relationship with the traders. New entrants, such as China’s own trading powerhouse, COFCO, and Glencore, an Anglo-Swiss firm, are also making the competition more cut-throat. Meanwhile, a series of bountiful harvests in North and South America in recent years has produced record stocks of grain, reducing prices.

To diversify Cargill’s sources of revenue, Mr MacLennan has sold $2bn-worth of assets since 2015, such as a second-tier American pork business, and invested $3.5bn in more value-added products, such as cooked meats, branded chicken, animal nutrition and food ingredients. Some current and former Cargill employees think such investments may be opportunistic, rather than enduring. If supply disruptions—bad weather, say, or a trade war between America and China—raised the volatility of food prices again, they expect Cargill to pour its capital back into bulk commodities. Though remaining committed to agriculture, Mr MacLennan rejects that idea. “If we were to do that, it would be a failure,” he says.

Moving closer to the consumer brings new sources of complexity. These include understanding widespread public rejection of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Though Cargill handles huge cargoes of GM corn and soyabeans, it has recently had some of its non-GM ingredients certified by an NGO which verifies that food is not bioengineered. This has angered the pro-GMO farmers that it serves.

Cargill is also making bets on early-stage technology. In August it took a share in a “meatless-meat” company, Memphis Meats, that produces beef, chicken and duck out of the cells of living animals, rather than from carcasses. This represents a potential insurgency against the conventional meat industry. Cargill is also co-investing with Calysta, a Silicon Valley startup, in a factory costing up to $500m that will produce up to 200,000 tonnes of fish food, known as FeedKind, made out of bacteria fed on methane. It is a novel approach to reducing the amount of freshly caught seafood, such as anchovies, in fish food, but is untested at scale.

Like counterparts facing upheaval in other industries, Cargill worries that the supply of food from farm to table is being disrupted. As Richard Payne of Accenture, a consultancy, puts it, the threat for traders is that farmers at one end of the supply chain use more technology to handle their own pricing, financing and logistics, and retailers at the other end of the chain, under pressure from tech-led firms such as Amazon, squeeze food manufacturers and their suppliers. Still, one-and-a-half centuries of business has taught Cargill not to get caught in the middle.

Source: economist

Cargill, an intensely private firm, sheds light on the food chain