SOUTH AFRICA’S stockmarket has Naspers largely to thank for its recent record highs. Shares in the media and internet group have soared by 45% this year; even before then it was Africa’s most valuable firm. So recent unrest among shareholders in Naspers might seem unwarranted. But in the days before its annual general meeting in Cape Town on August 25th, noisy debate erupted, chiefly about executive pay. Many investors reckon that Bob van Dijk, its boss, is being rewarded for success that he did little to create.

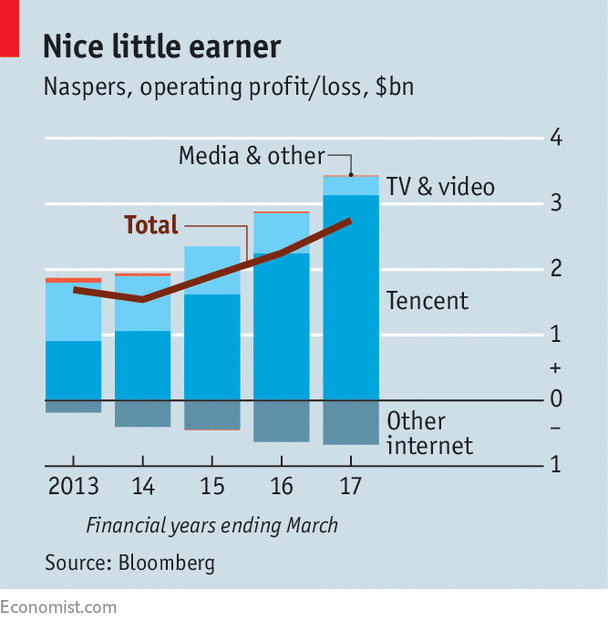

The source of good fortune for Naspers lies about 7,000 miles (11,265km) away. In 2001 Koos Bekker, Mr van Dijk’s predecessor, made a brilliant investment of $32m in a little-known Chinese technology firm called Tencent. Today its 33% stake is worth $130bn, as measured by Tencent’s value on the Hong Kong stock exchange; that dwarfs the $100bn valuation of Naspers itself on the Johannesburg stock exchange. Shares in the latter rise and fall on news from Hong Kong. In its last financial year, the firm’s share of profits from its Tencent holding in effect represented all of the group’s trading profits; the “rump” of the business, which Mr van Dijk has control over, lost money (see chart).

-

Whatever she may say, Theresa May won’t fight the next election

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

The roots of Afghanistan’s tribal tensions

-

Donald Trump’s shutdown threat intrudes on Virginia’s governor race

-

Immigrants boost America’s birth rate

So shareholders are dismayed that last year Mr van Dijk got a raise of 32%, to $2.2m. They say it is hard to see how much he is being rewarded for his own performance, and how much for that of Tencent. Although 79% of votes at the AGM were cast in favour of the pay policy, most are thought to have come from unlisted shares with special voting rights. Some of those shares are indirectly linked to company directors. Allan Gray, an influential asset manager, warned before the AGM that the pay policy was not aligned with shareholders’ interests. The majority of ordinary investors may have voted against. Mr Bekker, now the group’s chairman, swatted away any concerns. He compared corporate governance to star footballers washing their hands after going to the toilet: a nice idea, but less important than recruiting the best players for the team.

Shareholders have grumbled about pay at Naspers before, to no avail. The latest spat is more vocal and reflects deeper concern about its progress after two decades of reinvention. In the 1990s its prospects were uncertain. Founded in 1915 as Nasionale Pers (“National Press”), an Afrikaner nationalist publishing house, it was initially slow to acknowledge its long-time support of apartheid. With its roots in newspapers, it then had to adapt to the digital age. Mr Bekker refashioned it around new media, expanding its pay-TV business across Africa and investing in budding tech firms around the world.

Many of those investments have been slow to pay off. It was not long ago—the start of 2016—that Naspers was worth more than its Tencent stake but it is now worth less. The gap is widening. That may be because investors think Tencent’s shares, up by 70% since the start of the year, are overvalued, or because foreign capital is fleeing South Africa’s turbulent politics. But some see it as a sign that investors are losing patience with Naspers. Its e-commerce division posted trading losses of $731m last year. “The market has become increasingly disillusioned with the ability of management to pull rabbits out of the hat,” says Mark Ingham, an independent analyst.

Even the firm’s popular pay-television service, which has 12m subscribers across Africa, is struggling, because of tumbling local currencies that make buying American content more expensive, and fiercer competition from firms such as Netflix and StarTimes, a Chinese rival.

And yet the group may still defy the doubters over time. Its online classified-ads businesses, under brands such as OLX and letgo, together have 330m monthly users in 40 countries. Sean Ashton of Anchor Capital, which owns Naspers shares, optimistically reckons that total profits in the “rump” could soon grow faster than Tencent’s profits (which rose by 42% in 2016).

Although the Tencent effect draws criticism, it also means that Naspers has more money to experiment. At the AGM, Mr Bekker rejected the idea that Naspers should sell its Tencent stake and give a short-term boost to shareholders. It could be hard to find a buyer, and the Chinese government would probably want a say. For at least a while longer, the firm’s profits look sure to be made in China.

Source: economist

Naspers comes under fire for free-riding on Tencent