THOSE of a cynical bent might think Tom Stuker a glutton for punishment. Over the years, Mr Stuker has flown more than 18m miles (29m kilometres) on United Airlines, a carrier not always renowned for treating its passengers tenderly. Mr Stuker may possess the world’s most impressive frequent-flyer account. Over the past half-decade he has averaged over 1m miles a year with United.

Mr Stuker is extreme in his devotion. But engendering customer loyalty is something that nearly all firms strive for. Most fail. The average American household belongs to 28 loyalty schemes. The country is home to 3.8bn scheme memberships in total, according to Colloquy, a research firm, up from 2.6bn in 2012. More than half of these accounts go unused.

-

Why Stephen King’s novels still resonate

-

Are Americans sacrificing food and clothing to pay their taxes?

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

Why “affordable housing” in Africa is rarely affordable

-

What effect is Donald Trump really having on American tourism?

Frequent-flyer programmes, introduced in the 1970s, were the first examples of modern loyalty schemes. They proved to be a clever bit of marketing. Flyers value plane seats highly, so a free one feels like a substantial reward. But airlines can give away unsold berths at little incremental cost, because the jet would fly whether they are filled or not. Air miles are also sold to third parties, such as credit-card firms, which then use them to reward their own customers. For airlines, profit margins on frequent-flyer programmes can be 30-40%, says Pranay Jhunjhunwala of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), a consultancy, compared with 10% on flights in general.

Schemes like these are an example of “earn and burn” rewards, in which customers are rewarded for their purchases at a flat rate, whether a free flight for every 20,000 miles flown or a complimentary mochaccino for every nine swigged. According to Capgemini, another consultancy, nearly all firms with a loyalty scheme use this model.

Because they are so easy to implement, they are often used defensively. Many firms start a programme only because their competitors have one, says Steve Grout of Collinson Group, a loyalty consultancy. But they are so common that they end up generating little fidelity. Often “the market returns to stasis,” argued Lena-Marie Rehnen of the Ludwig-Maximilians University in a paper published in 2016. Some 77% of earn-and-burn schemes fail in one way or another within the first two years, according to Capgemini.

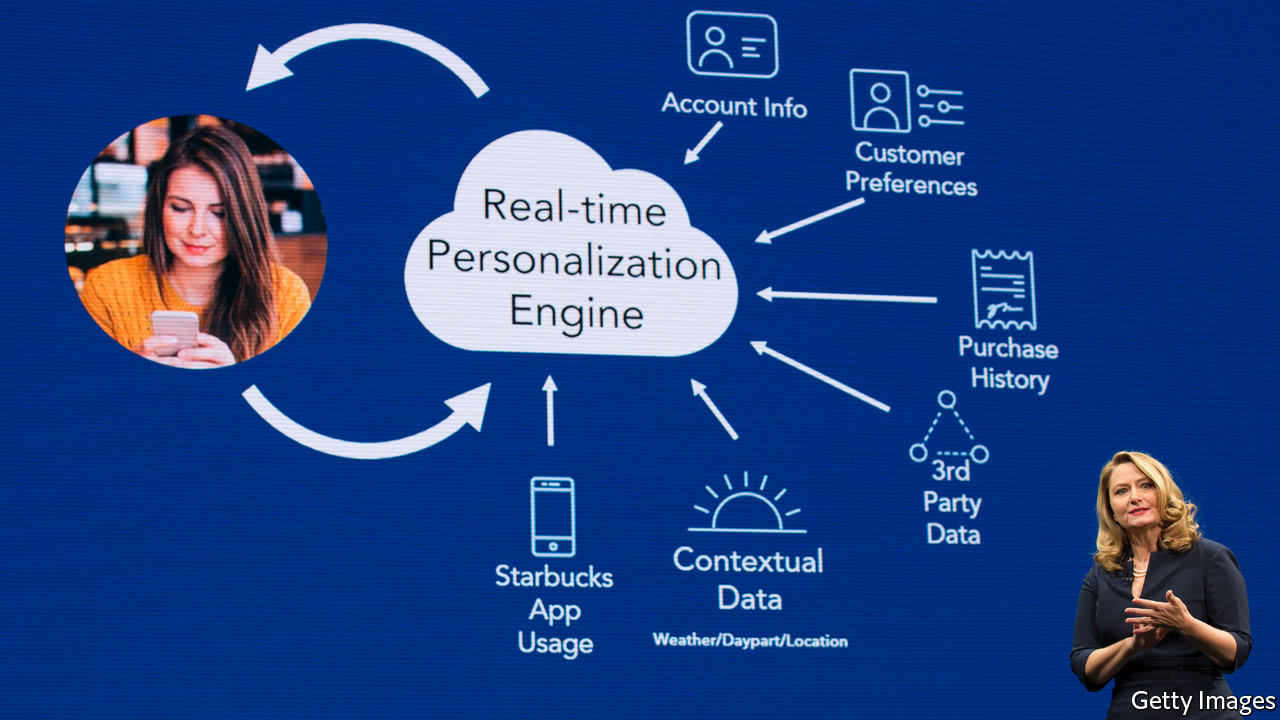

The best programmes, in contrast, get highly personal. Customers of Starbucks, for example, are encouraged to pay for their daily dose of caffeine using a smartphone app, which they pre-load with cash. (An estimated $1.2bn is deposited in Starbucks’s loyalty account.) This allows the firm to harvest reams of data on its patrons, including what they drink, at which stores and at what time of day—perhaps even whether it is sunny or raining when they choose a particular beverage. This information is then used to target members of the scheme with individual offers.

If that sounds a touch intrusive, Starbucks’s customers do not seem to mind. In its latest results in July, the firm boasted 13.3m active members. Over a third of its sales in America come through its reward programme. Customers tend to be happier handing over personal information when they get personalised offers in return, says Javier Anta, another BCG consultant. Some 97% of purchases at Kroger, an American grocery firm, are reported to be made by loyalty-card holders, who receive individual offers based on their shopping habits. Such data can be among the most valuable things a firm owns. When Caesars Entertainment, a casino group, went bankrupt in 2015, auditors valued its loyalty database at $1bn, more even than its property on the Las Vegas strip.

If data are the grist for the loyalty mill, then you might assume that the online giants would be running the best schemes. Yet this is not necessarily the case. Take Amazon. “Their philosophy is not good,” says one loyalty consultant (who asked not to be identified). “The amount they spend on promotions is insane.” Rather than offering across-the-board discounts, he says, Amazon would be much better served by designing and targeting customised promotions for particular shoppers as part of a loyalty scheme.

As Starbucks has shown, many advances in the loyalty industry are driven by mobile technology. For a start, it allows firms to use location information to send well-targeted, real-time offers. And storing scores of cards in an e-wallet, rather than having to wedge them into a purse, encourages shoppers to use them. A quarter of people who abandoned schemes did so because they did not offer a smartphone app, according to Colloquy. Smartphones are also increasing the number of ways in which customers can garner rewards. Some restaurants, for example, offer points for those posting photos of their meals on Instagram, or for “checking in” on Facebook. The only limit, it seems, will be customers’ desire to protect privacy.

Airlines, for their part, have been slow to keep up. Still, they have the odd card up their sleeves. In 2011, after Mr Stuker passed the 10m-mile mark, United Airlines named one of its jumbo jets after him. Even Starbucks would struggle to match that level of personalisation.

Source: economist

Mobile technology is revamping loyalty schemes