SEVENTH time lucky? Minutes of the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) policy meeting in July, published on September 26th, showed that the central bank had, for the sixth time since 2013, pushed back the date at which it expected prices to meet its 2% inflation target—to the fiscal year ending in March 2020.

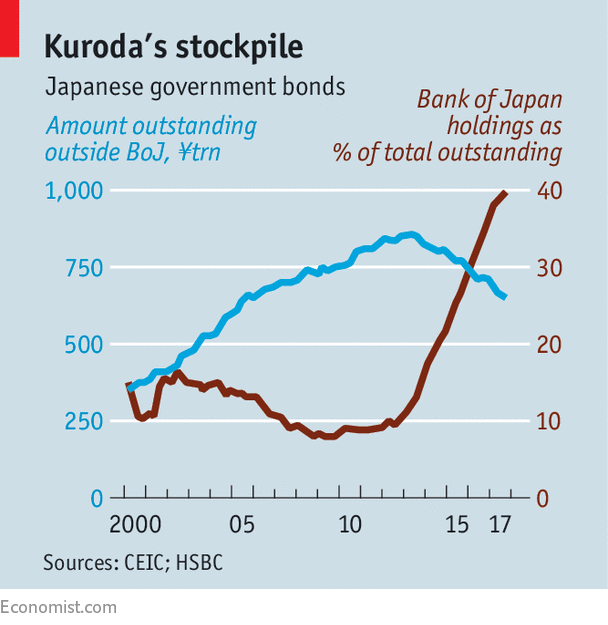

Four-and-a-half years since Haruhiko Kuroda took office as governor and embarked on an unprecedented experiment in quantitative easing (QE), the bank is still far from its goal. It has swept up 40% of Japanese government bonds and a whopping 71% of exchange-traded funds. The bank’s balance-sheet has tripled. It is now roughly the size of the American Federal Reserve’s.

-

Sotheby’s launches a new prize for cutting-edge curators

-

Why does Google look different in Europe?

-

Jeremy Corbyn’s Brighton speech marks the surrender of Labour’s moderates

-

The water crisis in Flint, Michigan has had terrible consequences for residents’ health

-

Saudi Arabia will finally allow women to drive

-

Why a Labour government might mean a fall in sterling

Yet, despite his apparent failure, and despite a snap general election, Mr Kuroda may yet stay for another five years when his term runs out next April. If not, most of his likely successors are signed up to the same reflationary policy. At least one member of the bank’s board gave warning at its most recent policy meeting on September 20th-21st that the measures it has taken are insufficient to stoke the desired inflation. These include keeping short-term interest rates negative, at about -0.1%, and ten-year government-bond yields at around zero. Soon, however, debate might turn to the feasibility of the 2% target.

Many countries would be happy to have Japan’s problems, says Masamichi Adachi of JPMorgan Securities: full employment, soaring corporate profits and the third-longest economic expansion since the second world war. But with government reforms faltering, the BoJ’s role as custodian of “Abenomics” (the policies of the prime minister, Shinzo Abe), seems assured. A labour crunch may at last be working where government badgering of Japanese companies to pay workers more has failed. In a speech this week, Mr Kuroda pointed to rising wages as a reason to hope inflation will pick up. Firms, he said, have been absorbing the cost to keep prices low, but will not be able to do so for ever.

Not all share his optimism. Monetary easing is failing in one of its aims, says Sayuri Shirai, a former BoJ board member: to foster risk-taking corporate behaviour. Instead, the amount of cash hoarded by Japan’s companies has grown by about ¥50trn ($443bn) over the past five years and exceeds ¥210trn, a record.

With sluggish investment and demand, Mr Kuroda’s monetary blitzkrieg will continue. The risk, says Ms Shirai, is that monetary policy has become a crutch for the entire economy. Leaning on the central bank, some companies are reducing efforts to boost productivity and improve governance, she says. And, by becoming the largest shareholder in several companies, the bank is distorting the pricing function of the market, adds Nicholas Benes, of the Board Director Training Institute of Japan.

Mr Kuroda stunned the markets with QE in 2013 and has continued to surprise since with a string of policy innovations. But nobody, says Mr Adachi, can see when the BoJ will start to reduce its asset purchases, let alone trim its balance-sheet. Perhaps never. For all the problems its easy-money policy brings, many think it more costly to ditch it than to keep on digging.

Source: economist

The Bank of Japan sticks to its guns