THE security guards at the foot of Antilia, a 27-floor private residence in Mumbai, while away the days just as all bored Indians have been doing in recent months—watching movies on their phone. Using a mobile network to stream endless Bollywood epics would until recently have been an unthinkable luxury, even in the rich world. In India it now costs less than a cup of street-side chai.

Thank the tycoon lording it in the skyscraper’s upper reaches. As boss of Reliance Industries, Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man, has spent more than $25bn on building Jio, a state-of-the-art mobile-telecoms network. The delight of the guards at Antilia, and of the roughly 130m Indians who have signed up to the service since it launched in September 2016, is matched only by the misery of Mr Ambani’s rivals.

Jio’s rise is nothing short of spectacular. It took less than a year for it to be delivering more data than any other mobile network in the world—one billion billion bytes a month, it claims, or over half the data delivered by all American carriers put together. Less so when it comes to revenue: after giving away its services for seven months, it went on to charge customers a third of what other Indian operators do.

Nobody thinks Mr Ambani is about to relent after winning a mere 11% or so of the market, a figure that is creeping up by around half a percentage point each month. Perhaps to terrify the competition further, he has spoken of wanting half the market to himself by 2021. To that end, the general public this week got their hands on the JioPhone, the latest plank in the company’s growth push.

A crossover between an antique Nokia-style feature phone (these still make up most new handsets sold in India) and a smartphone, the device is bound to appeal to Antilia’s security guards. It is free: you only pay a 1,500 rupee ($23) deposit, refundable after three years. Then, for a mere 153 rupees a month, customers can consume unlimited calls and data. Though the screen is small and popular apps such as Facebook are not (yet) available, analysts at CLSA, a brokerage, expect around 100m JioPhones to be sold in the next 18 months.

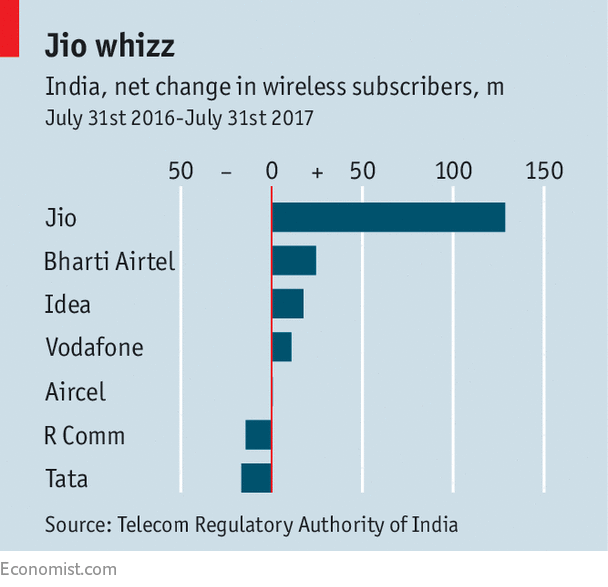

Jio’s gatecrashing of what was an orderly market has plunged its rivals into crisis. Some moan that regulators have bent over backwards to help Reliance, known for its ability to run rings around officials. Many operators are in precarious financial positions, having bet that rapid user growth would offset the high fixed costs of acquiring spectrum and building networks. Now that Jio has snagged 84% of the 153m net mobile-phone additions in the year to July (see chart), others must fight for the scraps. A key metric, average revenue per user, has cratered across the industry. What profits remain are insufficient to service large debt piles. Analysts at Credit Suisse, a bank, calculate that over half of around $40bn in loans to the industry sits with operators whose earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation cannot meet interest payments.

The government might get hit, too. Most lending to struggling telecom firms was by state-owned banks, whose long-overdue recapitalisation from public coffers will have to be bigger as a result. And the government itself is a creditor to telecoms companies, having agreed to spectrum bills being paid slowly over time. Against that, Mr Ambani’s bet is uniquely in sync with the current government’s ambitions. Jio launched its service with newspaper ads featuring a full-page portrait of the prime minister, Narendra Modi, dedicating its investment to his digital vision. And other services that need widespread internet adoption are clearly benefiting, from media-streaming to e-commerce.

Consolidation seems the order of the day for the rest of the industry. Having written €6.3bn ($6.9bn) off the value of its local subsidiary and shelved a likely share listing, Vodafone, the British-owned second-biggest player, is merging with Idea Cellular, the third-biggest. Reliance Communications, a smaller outfit once run by Mr Ambani (it ended up with his brother Anil after the family empire was split up in 2005) had been in talks with Aircel to combine, but the deal now seems to have fallen through. The smaller Reliance is flogging anything it can—from phone masts to its head office—in a bid to stay afloat.

Jio’s own financial position is hard to gauge. Its accounts are not separated from those of Reliance, whose profits generated in petrochemicals and oil exploration and drilling are funding the telecoms push. But even the most bullish analysts are struggling to figure out how Jio can provide a meaningful return to shareholders. Assuming it can double its existing customer base, it will still have sunk around $100 to acquire each new subscriber.

Investors are clearly impressed. They trust that Reliance’s increasing control over the fast-growing market for data will eventually allow it to raise prices. The firm’s shares are up by over 50% so far this year, having been flat for most of the past decade. At 60, Mr Ambani is staking his legacy on his new venture, the only major part of the Reliance empire he has created himself rather than inherited. Whatever he has in mind with Jio, he is not done yet.

Source: economist

Dirt-cheap mobile data is a thrill for Indian consumers