WHEN you are the chief executive of a public company, the temptation to opt for a merger or acquisition is great indeed. Many such bosses may get a call every week or so from an investment banker eager to offer the kind of deal that is sure to boost profits.

Plenty of those calls are proving fruitful. In the first three quarters of 2017, just over $2.5trn-worth of transactions were agreed globally, according to Dealogic, a data provider. The total was virtually unchanged from the same period in 2016, but the number in Europe, the Middle East and Africa was up by 21%.

It is easy to understand why an executive opts for a deal. Buying another business looks like decisive action, and is a lot easier than coming up with a new, best-selling product. Furthermore, being the acquirer is far more appealing than being the prey; better to be the butcher than the cattle. A takeover may keep activist hedge funds off the management’s back for a while longer. And being in charge of a much bigger company is a more demanding task that will surely justify (ahem) a larger salary for the executives in charge.

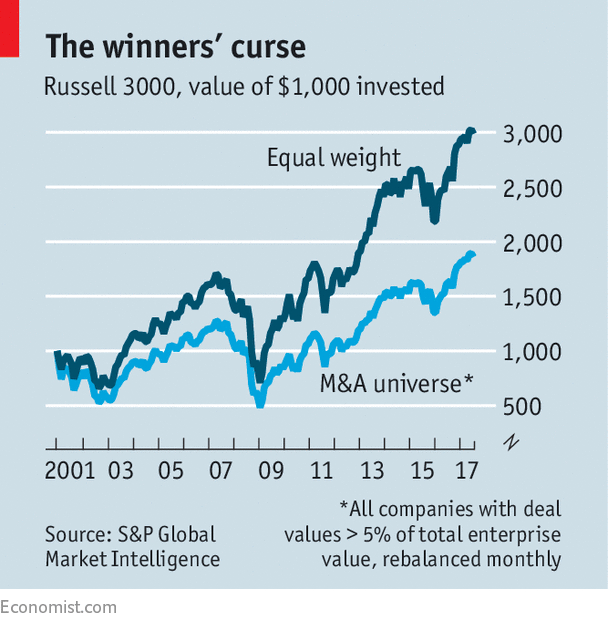

But these temptations, good and bad, should generally be resisted. S&P Global Market Intelligence, a research arm of the ratings agency, has updated a study on the impact of deals on the acquiring company’s share price. The study looked at M&A deals done by listed companies in America’s Russell 3000 index between January 2001 and August 2017; deals were only included if they cost more than 5% of the total enterprise value of the acquirer (5% of the equity value, for financial companies). The acquirers’ shares underperformed the market (see chart) and those of rival firms in the same industry.

That share-price performance was understandable, in the light of what tended to happen to the fundamentals of the acquiring company’s business. The study finds that, relative to the company’s peer group, net profit margins fall, as do the returns on capital and on equity; earnings per share grow less quickly; and both debt and interest expenses increase.

As the deal is done, however, the executives always sound bullish. Costs will be cut, the companies will benefit from selling a wide range of products and so on; a whole range of “synergies” will be achieved. Instead, the combined companies tend to suffer from clashes of culture and teething problems as systems prove hard to integrate. The AOL-Time Warner merger of 2000 is perhaps the most famous example of a dysfunctional deal; at the time, it was one of the biggest mergers in corporate history. Not every deal is that bad. But instead of two plus two equalling the promised five, all too often they add up to three-and-a-half.

Investors should look for a few useful warning signs ahead of a takeover. The faster the company was growing before the acquisition, the worse it tends to perform afterwards. Large deals perform less well than small ones. All-share deals tend to perform less well than cash offers. Yet, despite this, companies with a lot of cash on their balance-sheets tend to be bad at making acquisitions, perhaps because the money is too tempting for executives not to use. Like a Wall Street trader with his first bonus, they are tempted to spend the money on something flash.

Of course, not all deals underperform. So it is understandable that executives will tend to imagine themselves in that blessed minority that manages to make their acquisition a success. After all, without a degree of self-confidence, they would not have become chief executives in the first place. Fund managers who believe they can defy the odds and pick stocks that beat the market may also believe that they can distinguish the value-adding takeover deals from the rest.

The tough questions ought to be asked of, and by, the non-executive directors on acquiring-company boards. They should realise that executives like to build empires, and to be seen to be “doing something”; they should be the resident sceptics. Why should they believe this executive’s latest idea for a deal will be an exception to the rule?

Perhaps fewer deals will take place in any case. A report by Willis Towers Watson, an actuary, together with the Cass Business School, is more sanguine about the returns from mergers than S&P is, but suggests that political pressures will make it harder for deals to win approval from regulators. Rising populism means that governments may be less willing to let national champions be bought by foreign firms. Protectionism aside, this is one additional level of regulation that shareholders need not be too distressed about.

Source: economist

Mergers and acquisitions often disappoint