DEREGULATION, along with tax cuts and trade reform, is one of the three pillars of President Donald Trump’s economic agenda. Republicans promise that, freed of red tape, American firms will invest more and unleash faster economic growth. And while Mr Trump has yet to unite his party around a major piece of legislation, the White House has plenty of sway over regulatory policy. For a start, the government agencies Mr Trump commands can regulate and deregulate on their own (subject only to the instructions that Congress has given them in the past). How much red tape have they managed to tear down since Mr Trump took office?

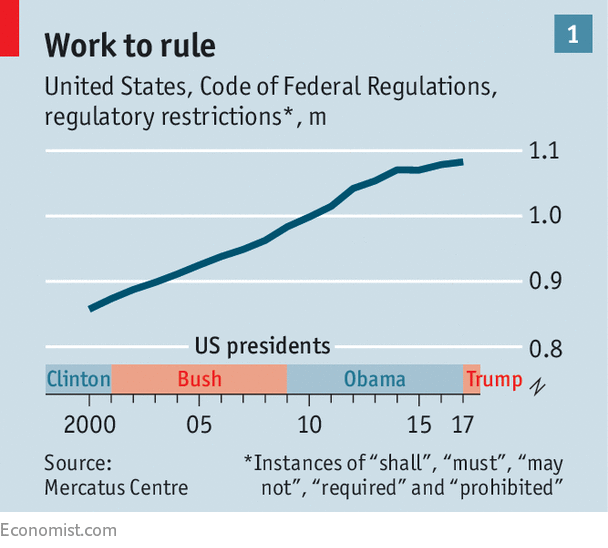

Regulation is difficult to measure precisely, but the long-term trend towards excessive rulemaking has been obvious. In 1970 there were about 400,000 prescriptive words such as “shall” or “must” in the code of federal regulations, according to the Mercatus Centre, a libertarian-leaning think-tank. Today there are 1.1m (see chart). Wonks of many stripes agree that this is far too many and that the rule book must be shortened. Agencies have rarely combed over old edicts to see whether they are worth keeping. The problem predated Barack Obama’s administration; both Republicans and Democrats have presided over regulatory expansions. That said, Mr Obama was an unusually prolific rule-writer, because for much of his presidency a hostile Congress meant that regulation was often his best tool.

-

Why malaria is spreading in Venezuela

-

More evidence for a link between Caesarean sections and obesity

-

Theresa May’s weakness at home is slowing down the Brexit talks

-

How “regularising” undocumented immigrants brings benefits

-

Raila Odinga takes a gamble by threatening to boycott Kenya’s election

-

Explaining the Finnish love of tango

Against this backdrop, the impact of the Trump administration has been dramatic. The flow of new rules is suddenly a dribble. Since Mr Trump was inaugurated the number of regulatory restrictions has grown at about two-fifths of the usual speed. In the last year of the Obama administration, the federal government wrote 527 regulations deemed “significant”. Mr Trump’s bureaucrats have penned only 118. And even that number is artificially high, because many of those edicts served only to delay or weaken Mr Obama’s rules. Examples of genuinely new regulations are few and far between. The White House has acknowledged only one—a rule aimed at reducing the amount of mercury dentists discharge into sewers, which went into effect in July.

Mr Trump has slowed rulemaking in two main ways. First, on coming to office, he ordered government agencies not to impose any net new regulatory costs on companies, regardless of the benefits of doing so, and said that in order to write any new rules they would have to repeal two old ones. Because it takes time to unearth and discard dud rules, the practical effect of this has been to put a brake on new issuance.

Second, Mr Trump has signed 14 bills stopping rules that were issued late in the Obama administration, and were therefore still subject to review by Congress, from going into effect. Not only were those regulations blocked (by means of the Congressional Review Act, or CRA); agencies will never again be able to write replacements that are “substantially the same” without lawmakers’ express approval. Before 2017, Congress had exercised its power to review regulations only once: in 2001, after George W. Bush came to office, it blocked a set of standards for chairs and desks aimed at stopping office workers getting back pain.

Yet wielding CRA as a deregulatory weapon has its limits, for Congress can review only rules issued during its previous 60 days in session. Tackling the bedrock of regulation is far harder. Three approaches are possible: later implementation of newish rules, looser enforcement of existing ones, and formal rollbacks of others.

Make America wait again

The first tactic, delay, is being used with abandon. For example, the Labour Department is trying to stave off parts of a new “fiduciary rule”, which requires investment advisers always to work in the best interests of their clients. (This requirement, like many seemingly simple rules, has somehow spawned hundreds of pages of legalese.) The fiduciary rule came into partial effect in June, but the administration is trying to postpone enactment of the remainder, which would give the edict teeth, by 18 months, to July 2019.

Delays do not always work. When Scott Pruitt, a sceptic on climate change who heads the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), tried to put off a regulation aimed at curbing emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, from oil and gas wells, a federal court found the decision to be “unreasonable”, and blocked it. “I can’t tell you how illegal that proposal was,” says Bill Pedersen, an environmental lawyer.

The second method—enforcing rules lightly, if at all—can be implemented through handy budget cuts. For example, Mr Pruitt has proposed slimming the agency’s budget by almost a third, though the idea met a frosty reception in Congress.

But it is the final approach, rescinding a regulation altogether, that is the trickiest to pull off. The EPA hopes to repeal the two main Obama-era environmental regulations: the Clean Power Plan, aimed at reducing carbon-dioxide emissions from power plants, and the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) rule, which expanded the scope of federal regulation of waterways. Neither has ever come into effect, because both have been delayed by lawsuits brought by states and affected firms. Some such challenges to Obama-era rules have ended successfully. A court in August struck down a Labour Department rule that greatly expanded the number of workers eligible for overtime pay.

Unless courts invalidate a regulation, though, undoing it is “like turning a battleship around”, says Steven Silverman, a lawyer who worked at the EPA for almost four decades. Agencies must start a fresh regulatory process, consult interested parties and show why their old cost-benefit analysis was wrong—a procedure itself vulnerable to legal challenges. While those play out, the Democrats could win back the White House and change course again.

For now, the administration’s tactic has been to try to stall the court cases, to keep the rules from taking effect, while they prepare replacements. But the administration may eventually have to convince judges that Mr Obama’s numbers were wrong. That will be easier in some cases than in others. Mr Obama’s administration often cast around for additional benefits to justify new rules. Sometimes, its methods were unprecedented. For example, the administration included the boon to foreign countries when totting up the value of reducing carbon emissions. The proposal to withdraw the Clean Power Plan, which was released on October 10th, shows that Mr Trump’s regulators have ditched that calculation. They have also taken a harder stand on so-called “co-benefits”, the positive side-effects of regulations.

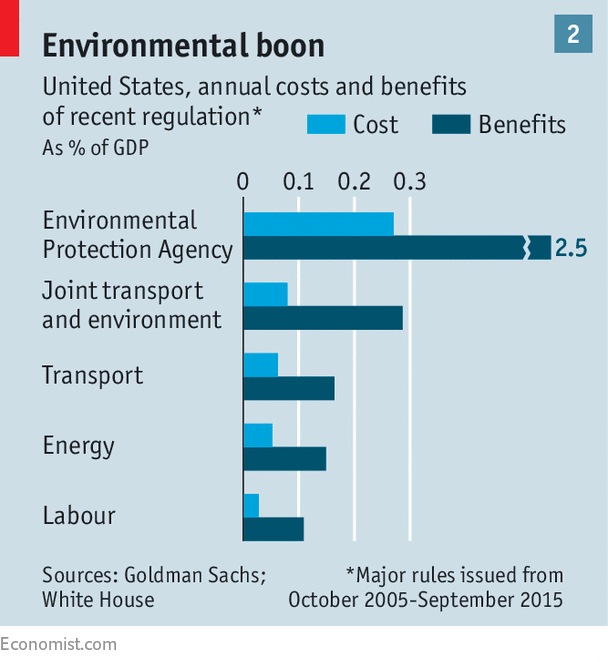

The question is how fast the Trump administration will run in the exact opposite direction. The White House is focused on reducing costs to companies; wider benefits barely seem to enter its thinking. This particularly threatens environmental regulations, which tend to have the biggest costs, but also the largest benefits (see chart 2). In reassessing the economic impact of WOTUS, the EPA took just a few short sentences to dispense with at least $300m in annual benefits to wetlands that had been included in the agency’s 2015 analysis. The Clean Power Plan replacement disregards entirely the effect that cutting carbon would have on reducing other noxious emissions that cause premature deaths—an omission that will surely invite a legal challenge.

Yet in other areas the administration seems more thoughtful than zealous. Take financial deregulation. In January Mr Trump made a crude promise to “do a big number” on Dodd-Frank, Mr Obama’s financial law, which has spawned thousands of pages of associated rules. Yet the two reports the Treasury has published on the subject have been detailed and rigorous. The first, on banking, contained a variety of relatively moderate proposals, such as raising the threshold above which banks must carry out “stress tests” from $10bn of assets to $50bn, and excluding cash and Treasury securities when calculating banks’ leverage.

The second report, released on October 6th, concerns capital markets. Equity markets do not seem to be doing their job well, it says, as seen by a fall in the number of public companies, possibly because of regulatory complexity. But elsewhere it warns of the risks that Dodd-Frank funnelled towards so-called “clearing houses”, such as LCH.Clearnet and Intercontinental Exchange. The Treasury argues that clearing houses should be subject to “heightened regulatory and supervisory scrutiny”.

Those are not the words of an administration bent on wanton financial deregulation. Instead, figures such as Jay Clayton, the new chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and Randal Quarles, whom the Senate confirmed on October 5th as the Federal Reserve’s vice-chairman for (bank) supervision, are likely to prune existing regulatory structures. In September the Fed and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) gave a taste of what is to come. They said banks may now be allowed to refile their “living wills”, which set out how they could be dissolved in a crisis, every two years rather than annually, so long as their business had not changed materially. This is hardly revolutionary, yet it is important to banks.

Some rulemaking is beyond the administration’s reach. On October 5th the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) said it would require payday lenders, who offer short-term loans at very high interest rates, to carry out new affordability checks before advancing credit. The agency will also limit lenders’ access to borrowers’ bank accounts. The CFPB can keep regulating in defiance of Mr Trump because—like the SEC—it is independent, meaning the president cannot dismiss its leadership without good reason.

Alternative facts

There can be little doubt that fewer federal regulations are in place today than would have been were Hillary Clinton president. But until many more rules face the chop, companies are unlikely to benefit all that much. Few mentioned deregulation in their second-quarter earnings calls this summer. When economists at Goldman Sachs, a bank, surveyed their stock-pickers in May, regulation was not considered the key policy issue in a single sector. Analysts emphasised tax reform instead.

The exceptions were watchers of technology, media and telecoms firms, who emphasised the importance of antitrust regulation. The Trump administration’s attitude towards consolidation in those industries, most notably a proposed merger between AT&T , a wireless giant, and Time Warner, a content empire, is unclear. Internet service providers (ISPs) would also get a boost if the Federal Communications Commission succeeds in loosening Obama-era rules on “net neutrality” (the principle that different sorts of web traffic should be treated equally).

Despite the lack of much true deregulation, the new approach in Washington does seem to have boosted business confidence. The “tone” of federal regulators has changed, notes one senior Wall Street executive, and slowing the flow of new rules has reduced regulatory uncertainty. Parts of Main Street agree: the percentage of small firms reporting regulation as their biggest concern has fallen slightly, from 20% a year ago to 16% today. Another sign, perhaps, is that the overall optimism of small businesses surged after the election to close to an all-time high, and has yet to fall back much.

Whether deregulation translates into faster economic growth will only become clear over time. The range of estimates regarding how much regulation affects growth is wide, while the quantity of evidence is thin. Economists at the White House point to a study by Mercatus which argues that if regulations had been frozen at their 1980 level, growth would have been 0.8 percentage points higher per year. Critics say that this actually implies a rather small growth effect, given that Mr Trump is taking aim at a relatively small number of Obama-era rules. The study also seems, implausibly, to blame regulation for a fall in investment after the financial crisis.

Ultimately, whether or not such claims are put to the test depends on whether the Republicans keep the White House in 2020. If they do, Mr Trump will have time to overcome the inevitable legal challenges to his agenda. America would probably see a large-scale deregulatory experiment. If they do not, the current period will look more like a regulatory hiatus than the beginning of a reversal.

Source: economist

An assessment of the White House’s progress on deregulation