THE new app for an upmarket British department store certainly looks the part. Released on Google Play, a shop for Android software, on September 5th, it has the right logo, the correct vibrant colour and offers fashionable clothes and accessories. But the app is not authorised by the brand, is littered with pop-up ads and is painfully slow (furious users gave it one-star ratings). Its developer, Style Apps, has also launched apps for other clothing brands that are household names in America.

Such fake apps are designed by crafty developers to trick inattentive users. Google and Apple police their app stores but many impostors get through. In third-party app stores, unofficial platforms run by someone other than the two tech giants, the problem is even worse. Users are tricked in two ways. Some apps fill a gap in the market. Selfridges, a chain of British fashion stores, for instance, has a legitimate app for Apple devices but not for Android ones. RadioShack, an American electronics retailer that filed for bankruptcy in February 2015, has a website but not an official app. Three imitation apps have by now sprouted under the shop’s name.

-

Taxing the rich

-

The rise of the podcast adaptation

-

Why malaria is spreading in Venezuela

-

Donald Trump’s latest travel ban faces fresh lawsuits

-

How “regularising” undocumented immigrants brings benefits

-

Explaining the Finnish love of tango

Other developers simply copy an existing app and hope users will fail to notice. The Economist found that half of the 50 top-selling apps in Google Play had fakes. These included ones with tweaked names (“MyGoogleTranslate” rather than “Google Translate”) and a bogus Netflix app that uses a weird Halloween-themed font for the logo. Google says it is reviewing these apps and will take action where necessary.

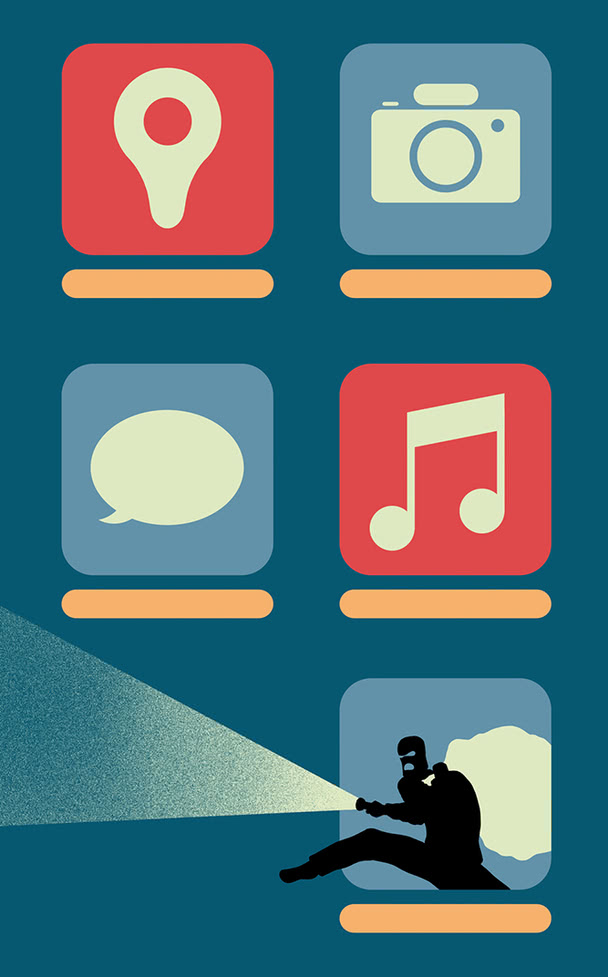

Fake apps are often stuffed with malicious code. Academics from a research group, SerVal, at the University of Luxembourg, estimate that around a fifth of all Android app-based malware is hidden in fake apps. The malware facilitates various money-making schemes. The most egregious are designed to steal the passwords that unlock users’ bank accounts. But it is more common for scams to profit from ordinary advertising, particularly on Android devices, says Eliran Sapir of Apptopia, a tech firm. Adverts in the smartphone’s web browser get quietly replaced by similar ones chosen by the fake-app developer.

Another money-spinner is to mine cryptocurrencies. Analysts at Trend Micro, a cybersecurity firm, in 2014 discovered that copies of Football Manager Handheld, a smartphone game, and TuneIn Radio, an audio app, contained malicious software that mined cryptocurrencies, the proceeds of which were probably funneled to the developers. This still goes on. It does not harm users directly, but researchers warn that such “vampire” apps drain phone batteries.

Developers can make much more money with fake apps than through legitimate means, reckons Mr Sapir. On dark-web forums, hackers and small-time digital advertisers offer developers around $1 per user per year to inject their apps with malicious code. In theory, a single app with 15,000 users (about a tenth of all apps have this many) could bring in roughly $1,250 per month. Most legitimate apps make about $1,000 per month, according to a survey from InMobi, a mobile-advertising company.

Fake-app developers are also quick to catch onto the latest trends. When Pokémon Go, a smartphone app based on a video game, became popular in July 2016, developers released a walk-through guide to the game which flooded smartphones with advertising. The guide was downloaded over 500,000 times. But the pickings are richest in retail, and especially in the autumn when fake-app developers are gearing up for spending binges during sales around Thanksgiving and Christmas, says Chris Mason of Branding Brand, a tech firm. Shoppers, beware.

Source: economist

Crafty app developers are ripping off big-name brands