THE port city of Kobe, on the southern side of Japan’s main island, is known for luxury beef from pampered cattle, fine sake and precision engineering. Its reputation for the last of those products took a blow on October 8th when one of its oldest industrial firms, Kobe Steel, admitted that that it had falsified data on many of its aluminium, copper and steel products. By October 11th, the company’s shares had fallen by a third, reducing its market value by ¥180bn ($1.6bn).

Kobe Steel has admitted to falsification over the past year relating to large quantities of four types of material; 19,300 tonnes of aluminium sheets and poles; 19,400 aluminium components; 2,200 tonnes of copper products and an unspecified amount of iron powder that was supplied to over 200 customers. These items were certified as having properties—such as a level of tensile strength, meaning stiffness—that they did not in fact possess.

-

Taxing the rich

-

The rise of the podcast adaptation

-

Why malaria is spreading in Venezuela

-

Donald Trump’s latest travel ban faces fresh lawsuits

-

How “regularising” undocumented immigrants brings benefits

-

Explaining the Finnish love of tango

No deaths or accidents have yet resulted, but the firm’s products are used by a long list of household names in Japan and overseas. Companies ranging from Boeing, Ford and GM of America to Hitachi, Nissan, Toyota and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries of Japan are rushing to examine their products’ safety. Mitsubishi has already said that affected steel was used in an H-2A rocket that safely launched a global-positioning satellite into orbit on October 10th.

Replacing the faulty metal sold may initially cost Kobe Steel just ¥15bn, according to J.P. Morgan, a bank. Yet taking into account the need to idle and repair any affected cars and planes, the overall cost could soar. More revelations may be on the way, for Kobe Steel admits that its current problems stretch back at least a decade.

The news has come at the worst possible moment. Like the rest of its industry in the rich world, Kobe Steel has been hit by a flood of cheap aluminium and steel imports. In 2016 it lost ¥23bn. In order to compete, mills will have to produce the sort of high-tech steel for cars, planes and trains that still commands premium prices, says Wolfgang Eder of Voestalpine, one of the few steel firms in Europe that is still profitable. Kobe Steel has lately switched its focus to higher-tech metals, but if it cannot guarantee their quality it will be in trouble.

The firm’s stumble is the latest in a long list of scandals for Japan’s once-bright corporate stars. Earlier this month Nissan was obliged to recall 1.2m cars after finding that unqualified inspectors had been conducting safety checks. In June, Takata, a maker of faulty airbags linked to 18 deaths worldwide, declared bankruptcy after being hit by a whirlwind of lawsuits. Last year, the bosses of Suzuki and Mitsubishi, two Japanese carmakers, resigned after their firms were found to have falsified fuel-consumption data on their vehicles. And between 2009 and 2011, Toyota, another carmaker, recalled 9m cars equipped with dangerous accelerator pedals.

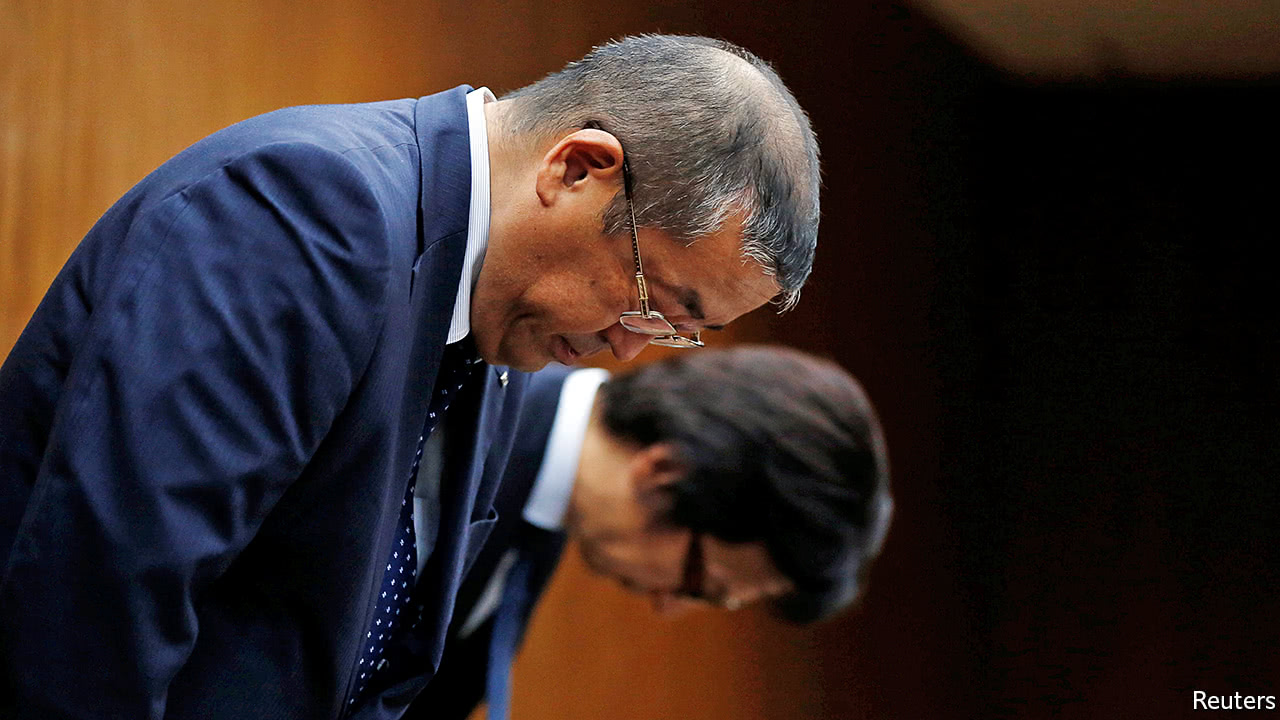

Such scandals are not unique to Japan. Volkswagen, a German carmaker, has been caught falsifying emissions data. Reckitt Benckiser, a British firm, sold cleaning products linked to the deaths of over 90 people in South Korea from 2011 onwards. But it is obvious that Japanese firms have not learned the lessons from recent scandals, says Toshiaki Oguchi of Governance for Owners Japan, a corporate-governance lobby group. A recurring theme is a lack of transparent leadership and a tendency to paper over problems. Japanese workers are ethical, he says, but tend to hide wrongdoing rather than confront management. Kobe Steel ignored at least one whistleblower who sounded the alarm over its substandard metal. Its president and chief executive, Hiroya Kawasaki, has promised to lead an internal probe.

His company’s woes add urgency to efforts to improve corporate governance in Japan. Shinzo Abe, the prime minister (who worked at the steel group before going into politics) has introduced a new stewardship code but “has not really had the stomach for a more serious fight over things like holding management more accountable,” says Tobias Harris of Teneo Intelligence, a risk consultancy. Scandals leave Japanese companies vulnerable to foreign takeovers. Takata, for instance, was snapped up by Chinese interests soon after it went bust.

Source: economist

Kobe Steel admits falsifying data on 20,000 tonnes of metal