ON OCTOBER 18TH, President Xi Jinping will preside in Beijing over the most important political event in five years. At the Communist Party’s 19th congress much will be made of the triumphs achieved in nearly four decades of reform and opening up. So expect a glossing over of one part of that process where progress has largely stalled: the “internationalisation” of China’s currency, the yuan.

This seems odd. Just a year ago, the yuan became the fifth currency in the basket that forms the IMF’s Special Drawing Right (SDR). This marked, in the words of Zhou Xiaochuan, China’s central-bank governor, in a recent interview with Caijing, a financial magazine, “historic progress”. Symbolically, China’s monetary system had been awarded the IMF’s seal of approval. A further boost to prestige was the announcement in June this year that some Chinese shares would be included in two stockmarket benchmarks from MSCI.

-

In “Rest”, Charlotte Gainsbourg explores the sharp edges of grief

-

Taxing the rich

-

The rise of the podcast adaptation

-

Why malaria is spreading in Venezuela

-

Donald Trump’s latest travel ban faces fresh lawsuits

-

How “regularising” undocumented immigrants brings benefits

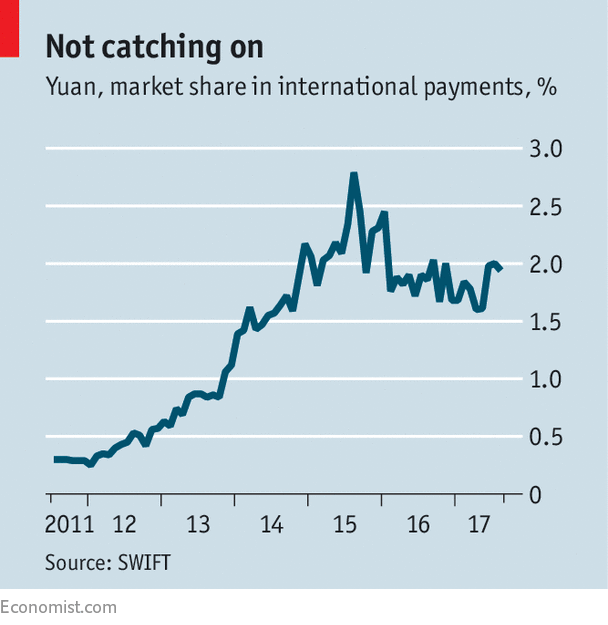

Yet the yuan’s international reach has in fact fallen in the past two years. It has regained its ranking as the world’s fifth most active for international payments, after slipping to sixth in 2016. But its share of this market has slipped from 2.8% in August 2015 to 1.9% now (see chart). Use of the yuan in global bond markets over this period has fallen by half, as companies have instead raised funds within China. In Hong Kong, the largest offshore market, yuan deposits have plunged by 47% from their peak in December 2014. Of the foreign-exchange reserves held by the world’s governments, just 1.1% are in yuan, compared with 64% for the dollar.

The constraints on the internationalisation of the currency are largely self-imposed—and in many cases predated admission to the SDR. A minor devaluation of the yuan in August 2015, intended to make the currency more flexible, was botched. This led to speculation about further falls in the yuan’s value, and forced the central bank to tighten capital controls and spend foreign-exchange reserves to prop it up.

Since January this year, China’s reserves have been growing again. But stringent capital controls remain in place. In his interview Mr Zhou called for a renewed drive to free up China’s financial system, citing a “troika” of targets: increased foreign trade and investment; a more market-based exchange rate; and a relaxation of capital controls. He said there was a “time window” for this. If missed, the cost of reform would be higher in the future.

Few observers, however, take Mr Zhou’s comments as official policy. In office since 2002, he is expected to be replaced next year. He represents one side of a continuing debate. In September two capital-control rules were indeed eased, but foreign traders tended to share the view of Mitul Kotecha of Barclays, that the move was purely cosmetic. In the words of Eswar Prasad, an economist at Cornell University and author of “Gaining Currency”, a book about the yuan, “what the government giveth, the government can taketh away.” Most foreign investors are all too aware of that.

So the currency’s international advance is unlikely to resume soon. More likely is a gradual opening of yuan markets. One avenue is to standardise systems such as the China International Payment System, which processes cross-border payments. Another is to expand the Bond Connect and Stock Connect programmes that link Chinese markets to Hong Kong. A third involves China’s intense diplomatic drive to push its “Belt and Road Initiative”, involving massive investments in infrastructure to boost transport, trade and investment links between China and Central Asia, Europe and Africa.

However, David Woo of Bank of America Merrill Lynch argues that none of this is likely to lead to a big surge in foreign holdings of Chinese financial assets. That will depend on the liberalising measures Mr Zhou is advocating, as indeed does the future shape of the Chinese economy. “There isn’t a single country,” Mr Zhou argued, “that can achieve an open economy with strict foreign-exchange controls.”

But his apparent belief that measures already taken, such as joining the SDR basket, have set the yuan on a remorseless path towards internationalisation has been contradicted by the experience of the past two years. The party’s watchword remains “stability”. And whatever the benefits of capital-account liberalisation, it would bring a measure of unpredictability. In a battle between openness and control, Mr Xi is likely to favour control.

Source: economist

The internationalisation of China’s currency has stalled