FOR a moment it seemed China was reverting to Maoist economic management. On the sidelines of the Communist Party congress this month, an official told Xi Jinping that her village distillery sells baijiu, a potent spirit, for 99 yuan ($15) a bottle. Mr Xi, China’s most powerful leader since Mao, remarked that this seemed a bit dear. The chastened official thanked him and pledged to follow his guidance. But Mr Xi gestured her to stop. “This is a market decision,” he chuckled. “Don’t cut the price to 30 yuan just because I said so.” The audience, perhaps relieved that Mr Xi had no intention of dictating the price of booze, broke into laughter.

This rare spot of levity at the dreary five-yearly congress was telling. The occasion cemented Mr Xi’s unrivalled position at China’s apex. For companies, the question is what he will do with it. His vision can seem ominous. “North, south, east and west—the party is leader of all,” he intoned in a speech laying out his plans.

-

Fears that Xi Jinping is bad for private enterprise are overblown

-

Zaryadye Park in Moscow is an architectural triumph

-

The financial markets are not the whole economy

-

Congestion in London is driving people off the buses

-

Scott Pruitt seeks to weaken independent scientific review at the EPA

-

South Korea’s soaring minimum wage

On his watch the party has already reasserted control over state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and sought influence in private ones. It has called on entrepreneurs to be patriotic. And regulators have cowed swashbuckling businessmen, from Wang Jianlin, a property mogul formerly China’s richest man, to Wu Xiaohui, an insurance magnate who fancied himself the next Warren Buffett.

It might seem as if Mr Xi is turning the screws on private enterprise. But “socialism with Chinese characteristics” has long had a contradiction at its heart. Across much of the economy, Communist officials preside over rumbustious capitalism. Mr Xi’s pledge of a “new era” probably means more of the same rather than a relapse to central planning.

Take the clampdown on moguls. Regulators have chosen four of China’s most acquisitive companies for extra scrutiny: Anbang, an insurance firm; HNA, an aviation-to-tourism group; Wanda, a property developer; and Fosun, an industrial conglomerate. As a result, their frenetic overseas investments have slowed sharply this year. Wanda has sold many hotel assets. Anbang’s founder has been detained.

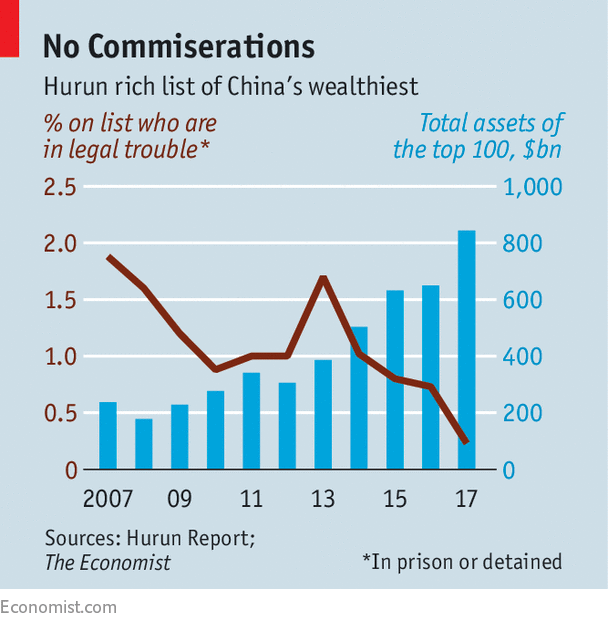

Yet this is not the assault on entrepreneurs that some make it out to be. Of the 2,130 people on the Hurun rich list, a guide to China’s ultra-wealthy, just five fell foul of the law last year (see chart). By comparison, Mr Xi’s anti-corruption campaign has ensnared nearly 10% of the party’s 205-member central committee in five years.

Restrictions on the four high-flying companies are best seen as a by-product of stricter financial regulation, says Joe Ngai of McKinsey, a consultancy. Belatedly, officials have taken a hard line on risky funding, especially for overseas acquisitions. At the same time, the fortunes of tycoons with businesses geared to the domestic market—in tech, property or manufacturing—have soared. Wealth on the Harun list has more than doubled under Mr Xi.

Another concern is tightened control of the technology sector. The Wall Street Journal reported this month that internet regulators might take 1% stakes in social-media giants, including Youku, Alibaba’s YouTube-like platform, and Weibo, China’s answer to Twitter. But the government already has a good handle on its tech superstars. None can get far in China if it angers the party or turns down data requests from state security. And they already serve up party-pleasing products. Some are lighthearted, like Tencent’s game for WeChat, its ubiquitous mobile app, letting users compete in “applauding” Mr Xi’s speech by tapping their phone screens. Others look more sinister, such as techniques to monitor users, which can help authorities keep tabs on citizens.

The notion that Mr Xi is stifling innovation is belied by a flourishing of enterprise. Only America has more, and more valuable, startups. Media focused on the party instruction for entrepreneurs to be patriotic, but the directive mostly spelled out how the government can support them. Gary Liu, president of the China Financial Reform Institute, says the real message is that entrepreneurs are vital to the economy.

A final concern is Mr Xi’s wish to strengthen the party’s clout in the corporate sector. Hundreds of listed SOEs have amended their articles of association since he took office, vowing to consult party committees on big decisions. The regulator which oversees tech companies last year ordered them to improve their “party building” activities. The party wants members to be placed in more important jobs. Tencent now employs some 7,000 party members, or 23% of its staff; it says that 60% of them are in key roles.

But this is not entirely new. After mass closures of SOEs in the 1990s, officials pressed private firms to set up party organisations. As far back as 1999 nearly a fifth of foreign-backed companies had one. There is scant evidence that party cells have tried to sway firms’ big decisions. Companies may not like them but the cells do not hurt business. Industrial profits averaged nearly 10% of GDP during Mr Xi’s first five-year term, the highest since China’s economic reforms began four decades ago.

The party could yet use its cells as beachheads for more control. Regulation of tech firms may get more intrusive. Feeling vulnerable, many of China’s wealthiest entrepreneurs hold foreign passports. But the party knows that a healthy economy needs a vibrant private sector. Perhaps the biggest risk is that, even if Mr Xi means well, the accumulation of so much power in one leader can itself have a chilling effect. A few days after his baijiu remark, the distiller announced that it would sell a new blend at 30 yuan a bottle.

Source: economist

Fears that Xi Jinping is bad for private enterprise are overblown