REVIVING the original Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade deal between 12 countries around the Pacific Rim, is technically impossible. To go into force, members making up at least 85% of their combined GDP had to ratify it. Three days into his presidency, Donald Trump announced that America was out. With 60% of members’ GDP gone, that deal was doomed.

But on November 11th, another began to rise in its place, crowned with a tongue-twisting new name: the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Ministers from its 11 members issued a joint statement saying that they had agreed on its core elements, and that it demonstrated their “firm commitment to open markets”. The political symbolism was powerful. As America retreats, others will lead instead.

-

What Buddhism teaches about peace and war

-

Transcript: An interview with Doug Jones

-

The Trump tax cuts fall far short of Ronald Reagan’s reforms

-

Wine-making existed at least 500 years earlier than previously known

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

The CPTPP is still far from finished, however. This inconvenient truth is unsurprising. Resuscitating the deal without its biggest member was always going to be hard. Without America, uncomfortable concessions made in the old TPP can seem less worthwhile. But any attempt at a full renegotiation risked the entire deal unravelling. If countries used the opportunity to grab new concessions in their pet areas, others could make counterclaims and talks could descend into a protectionist mess.

The few unresolved areas reflect these challenges. Malaysia wants more time to adjust to rules governing its state-owned enterprises. Brunei wants a more lenient approach to its coal industry. And Vietnam, which stood to gain most from extra access to the American clothing market, wants more time before it could face sanctions for violating the pact’s labour laws.

Trade ministers from Mexico and Canada had a particularly tricky task, given their involvement in trade negotiations with the Americans about the North-American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Anything Mexico and Canada conceded in the TPP could then be unusable as a bargaining chip in separate talks with Mr Trump. The talks took a dramatic turn on November 10th when it seemed as though agreement had been reached, only for the Canadians to backtrack. (According to Wendy Cutler, an American negotiator of the TPP, such tactics are not unusual.) The Canucks want better access to the Japanese vehicle market and worry that a CPTPP agreement on cars will complicate the politics of NAFTA negotiations; they also want more freedom to force companies to develop Canadian cultural content.

For their part, Japanese negotiators were keen to create an incentive for America to join the CPTPP in the future. Some of the original rules could benefit America even outside the pact, blunting its incentive to rejoin. But ditching too many of them might cause the benefits of the original to be lost.

Aside from the areas still under discussion, the ministerial statement listed 20 carve-outs from the original pact. Rules that gave special treatment to express shipments, a sop to American companies like DHL and Federal Express, will be suspended. So will protection for intellectual property, also fought for fiercely by American negotiators. (If America did want to rejoin, then in theory it could negotiate these clauses back into force.) Contentious rules allowing investors to take governments to court have been narrowed in scope. States can force investors to sign agreements waiving their right to sue under the CPTPP.

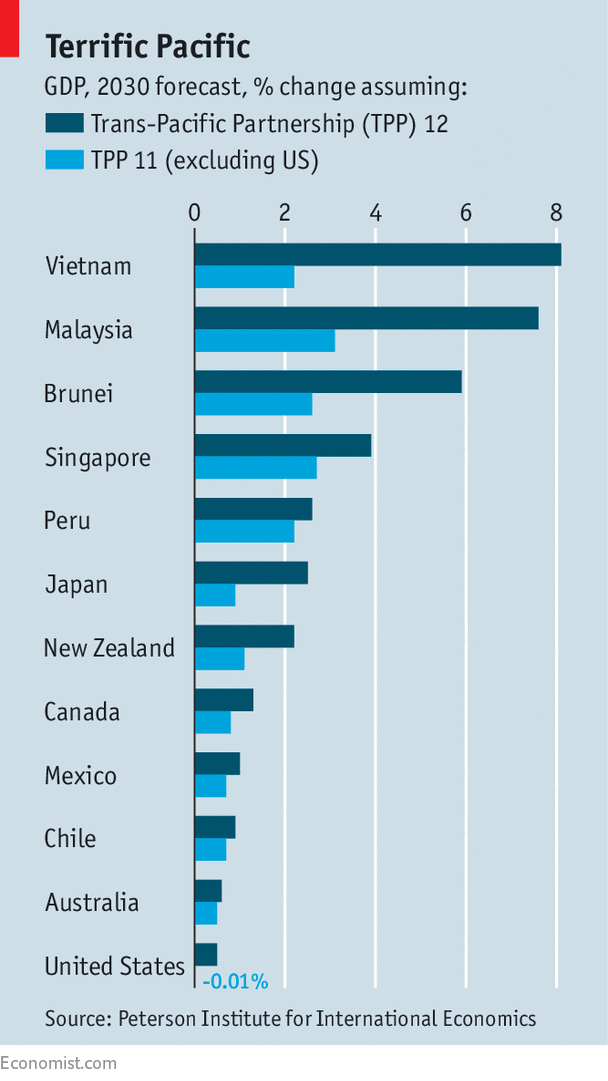

Despite these difficulties, so far the CPTPP looks impressively similar to its parent. It seems the new deal will preserve the market access agreed upon in the TPP. And although differences remain, they do not seem like show-stoppers. America’s absence reduces the economic gains from the agreement but does not eliminate them (see chart). Giving up on the pact would squander years of talks as well as the opportunity to upgrade existing trade deals and spur economic reforms. The plan is to finalise a CPTPP deal in the first quarter of 2018. Even if America has rejected its own rules, others still see value in them.

Source: economist

Who needs America?