Corporate debt is at its highest level relative to U.S. GDP since the financial crisis , and while not now a concern, that mountain of corporate IOUs could quickly turn into a heap of worry under the right circumstances.

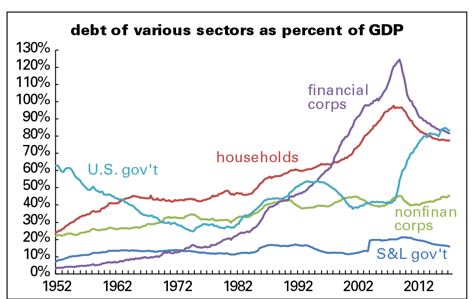

Fueled by low interest rates and strong investor appetite, debt of nonfinancial companies has increased at a rapid clip, to $8.7 trillion, and is equal to more than 45 percent of GDP, according to David Ader, chief macro strategist at Informa Financial Intelligence.

According to the Federal Reserve, nonfinancial corporate debt outstanding has grown by $1 trillion in two years.

“Everything is fine until it isn’t,” Ader said. “We don’t need to worry about that until we’re in a slowdown and profit declines.”

Low rates have encouraged companies to borrow, but instead of using the money to expand, they have used it to boost their share prices, he said.

Source: Informa Financial Intelligence

The corporate debt market has been in the spotlight after this month’s sell-off in high-yield bonds triggered concerns the riskiest issues may be sending a warning to the broader markets, including the much bigger investment-grade debt market and stocks.

The high-yield market is different from the investment-grade market in that it reacts more as a risk market, like stocks.

Strategists look at the sell-off as mostly a correction, centered on certain sectors in the riskiest part of the credit market. Telecom and health-care junk bonds were the hardest hit, as investors pulled a near-record $6.8 billionfrom high-yield funds in the week through last Wednesday.

“We’re keeping an eye on it but it looks like it was one of those typical productive corrections, rather than the beginning of the end,” said Robert Tipp, chief investment strategist and head of global bonds and foreign exchange at PGIM Fixed Income.

With a growing economy and strong profit picture, there is little concern now about the overall corporate debt market, which so far is not reflecting overly aggressive borrowing against inflated assets, Tipp added. Companies have a lot of cash on hand, and “against that you can find cases of credits that are extended but you can also find a lot of pretty presentable credits.”

Investment-grade corporate debt is closing in on a record for 2017, with $1.274 trillion in issuance year to date, versus last year’s total $1.286 trillion, according to Informa Global Markets.

The new issue market was active Monday, with five investment-grade and six high-yield issues expected to price. The average estimate for this week’s investment-grade issuance was $7 billion, reflecting a lighter holiday week volume, but that could turn out to be higher, according to Chris Reich, senior analyst at Informa Global Markets.

High-yield debt issuance so far this year totals $240.9 billion, higher than 2016’s $217.1 billion but lower than prior years, which peaked at $336 billion in 2012, according to Informa.

Rick Rieder, BlackRock’s global chief investment officer of fixed income, said he is not concerned about the leverage but warns there’s something reminiscent of previous crises.

“The only thing I would say that is concerning — there is some rhyming nature to the fact there are no covenants in deals anymore and structure doesn’t matter anymore,” he said. “That does give you some pause. I’m not worried about the leverage. It’s not going to be a 2018 dynamic. I am worried about longer term that some of the lack of covenants or collateral or structure,” he said.

There are major changes underway that could, in theory, slow the amount of issuance. One is the tax law proposal that would treat foreign profits differently and no longer encourage corporations to keep money overseas. Some major companies have issued debt against their foreign cash to buy back stock or pay out bigger dividends, said Ader.

Another change is the proposal to restrict the amount of corporate debt interest a company could write off. Strategists say the law affects mostly the most indebted companies in the high-yield market.

Source: Liscio Report

The overall fixed income market will also feel the effects of global central banks moving away from easy policies. The Fed, expected to raise rates at its December meeting, has also forecast three rate hikes for next year. It is also expected to actively reduce the amount of purchases it is making in the Treasury and mortgage markets. The European Central Bank is also paring back its purchases of debt.

Andrew Brenner, global head of emerging markets, fixed income at National Alliance, said he thinks the sell-off in high yield could be over for now, but it may come back in the beginning of next year as the European Central Bank begins to wind down its bond purchases and the Fed looks set to raise interest rates.

“It’s not different this time. The leverage is a problem, but the leverage is not a problem right away because interest rates are very low,” he said. “It makes sense for corporates to do this.”

Tipp said the new Fed, expected to be led by Trump nominee Jerome Powell, may not be as aggressive as some believe, or even as hawkish as it’s been in the final year of Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s tenure.

“The markets have taken it in stride,” Tipp said. “If the economy keeps cruising along, but they don’t get the inflation number to hike, it could be a very good year for the market.”

Economic expansion is not showing signs of nearing an end, but once in a while the markets will take a pause. Disruptions could come if tax cuts and the resulting stimulus don’t happen, or if the market is derailed by the Fed or the ECB, or even by some political event, he said. “That’s when you have a correction.”

Source: cnbc economy

The debt time bomb that keeps growing and now equals nearly half of US GDP