FOR millennia, man has broken rocks. Whether with pickaxe or dynamite, their own or animal muscle, in a digger or a diesel truck, thick-necked miners have been at the centre of an industry that supplies the raw materials for almost all industrial activity. Making mining more profitable has long involved squeezing out more tonnes of metal per ounce of brawn. Now robots, not man, are settling themselves into the driving seat.

Rio Tinto, one of the world’s largest mining firms, is leading that transformation in its vast iron-ore operations in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. It is putting its faith in driverless trucks and unmanned drilling rigs and trains, overseeing them from the office equivalent of armchairs about 1,000km (625 miles) south, in Perth. Jean-Sébastien Jacques, Rio’s chief executive, says it is ten years ahead of mining rivals in autonomous technology. For him and for Simon Thompson, a new chairman appointed on December 4th, the question is how much such technology can tame another ancient feature of mining: the boom-and-bust cycle.

-

Supervisors declare global bank-capital standards completed

-

Donald Trump’s Jerusalem move sparks Christian disputes

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

What the Yugoslav war-crimes tribunal achieved

-

Democrats take a strong line on sexual misconduct in Congress

On a visit to Rio’s Hope Downs 4 mine in the Pilbara, it is eerie at first to watch 300-tonne trucks speeding uphill in a cloud of red dust with no one in the cab. Then it becomes endearing, as you watch supersized robotic mammoths so safety-obsessed that when sagebrush blows in their way, they judder to a halt.

As for the mine’s managers, they are struck by the silence; there is no longer a steady stream of banter across drivers’ two-way radios. They also welcome the productivity gains. Over a 12-hour period, they say, manned trucks are competitive, but over 24 hours and longer, the absence of coffee breaks, fatigue and driver changeovers begins to tell. The autonomous trucks stop only once a day for refuelling. “Then you pat them on the bum and out they go again,” one says. He adds that the workforce at the mine is already about one-third lower as a result of automation. The 76 autonomous vehicles in Rio’s 400-strong truck fleet in the Pilbara are an estimated 15% cheaper to run than the rest.

Two hours’ flight away, at Rio’s operations centre in Perth, engineers remotely control the equipment with screens and computers. “You have to blow dust in their faces to make them feel like they’re in the Pilbara, otherwise it’s too comfortable,” quips an executive, as he oversees desk-bound employees operating two of Rio’s six autonomous rigs digging into the Pilbara rock. Rio’s boss of iron ore, Chris Salisbury, says that autonomy enables drilling to run for almost a third longer on average than with manned rigs, and to churn through 10% more metres per hour. The extra data collected helps the firm to evaluate the quality of the ore for further digging.

Next year Rio hopes to win regulatory approval to run the world’s first driverless trains along 1,700km of track between its 16 iron-ore mines and four ports in the Pilbara. It completed a 100km test run in September. According to Mr Salisbury, autonomy can provide a 6% improvement in average speed, and the elimination of three driver-changes in each 40-hour period. This may sound small, but it adds up. Trains will also run closer together, adding more to the system at any one time.

Although Rio introduced its first driverless trucks almost a decade ago, the move to autonomy has been slow, involving finicky fine-tuning with suppliers. Mr Jacques says technological improvements will provide only a third of the $5bn in additional free cashflow, chiefly from its iron-ore and aluminium operations, which Rio intends to generate over the next five years. But from 2021 onwards he expects new technologies, and autonomy in particular, to be a bigger driver of returns. By then Rio intends to start iron-ore production at Koodaideri in the Pilbara, which it says will be the first mine designed to be “intelligent”, at a cost of $2.2bn.

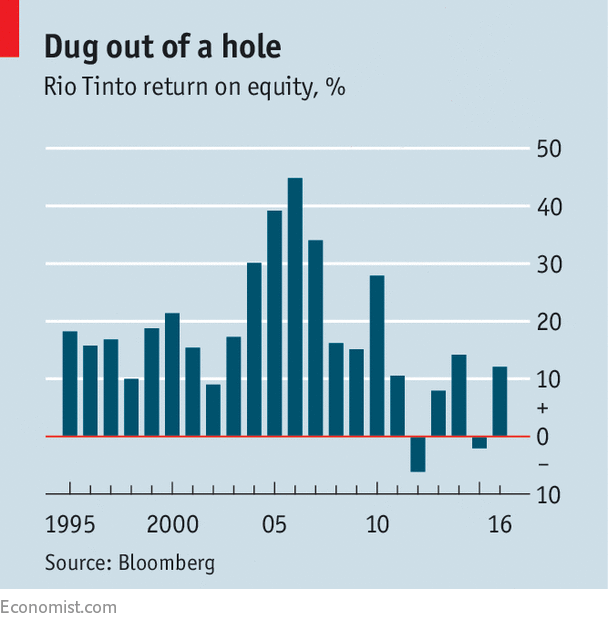

Rio also intends to squeeze out higher returns with more disciplined spending and improved quality. For investors a focus on the bottom line is reassuring—especially as much of Rio’s spare cash is being returned to shareholders in the form of dividends, or being used to de-leverage the balance-sheet. It also makes a change. Under previous management, Rio’s splurges on overpriced assets, such as Alcan, a Canadian aluminium company, in 2007 during the China supercycle, and Riversdale, a coal mine in Mozambique, in 2011, clobbered returns (see chart).

In a sign of their concern, some big shareholders railed against the possibility that Sir Mick Davis, a dealmaking supremo who once led Xstrata, another mining company (and who is now the chief executive of Britain’s Conservative Party), would be named as chairman. Mr Thompson, a financier and former executive at Anglo-American, another mining rival, is seen as a more conservative choice.

His first big task will be to deal with the legacy of Rio’s spendthrift era. In October America’s Securities and Exchange Commission charged the firm, its former boss, Tom Albanese, and another former executive with fraud. It alleged that they failed to disclose the loss of value of the Mozambique transaction to Rio’s board, its auditor or investors, and also released misleading financial statements shortly before raising debt in America. (Rio and its ex-employees deny the charges.)

These headaches aside, the firm’s core mining business is in comparatively good shape. China’s demand for the high-grade iron ore that is a speciality of Rio’s Pilbara operations is buoyant; iron ore accounts for about two-thirds of its earnings. Aluminium demand is also likely to grow briskly, thanks in part to demand for lighter cars. Mr Jacques insists that Rio will not make overpriced acquisitions even to secure prized battery minerals such as lithium. The future may be driverless, but steadier hands appear to be on the wheel.

Source: economist

Rio Tinto puts its faith in driverless trucks, trains and drilling rigs