Apple doesn’t sell many products — you can probably count most of them on your hands and feet.

But it’s hard to overstate the company’s scale and power. As the most valuable franchise in the world, Apple own more U.S. Treasury securities than many major countries, was the fourth-largest purchaser of solar power in 2016 as measured by megawatts, is the top retailer per square foot and even had a 140-acre wetland built in Oregon, in part to cool an Apple data center.

Then there’s the massive supply chain. Apple’s products are so intricate and require so many outside contributions that 36 publicly traded companies count on the iPhone maker for at least 10 percent of their revenue, according to FactSet.

That’s far more than the number of companies that rely on Google, Microsoft or Amazon, whose ecosystems have each been covered as part of a year-end CNBC series on tech giants and their growing dominance.

One of the biggest challenges of working with Apple is the high level of secrecy around its products. Not only does the company limit what suppliers can say about the relationship, but partners often don’t know Apple’s future plans for its phones, watches, computers and other devices. As a result, they can be blindsided by Apple’s decision to go another route or to even build rival technology itself.

Apple has a long history of demanding high levels of customization in its hardware, giving suppliers little choice but to focus on iPhones.

Investors in Imagination Technologies, which counts on Apple for 45 percent of revenue, know this story all too well. The stock plunged as much as 71 percent in a single day after an announcement that Apple would stop using its graphics processors. (The company was acquired by a private equity firm a few months later).

Apple had been working on its own technology to replace Imagination’s chips, presumably for some time. The company’s research and development efforts pointed to a potentially new revolutionary product, like a car. But Apple was actually developing processors and sensors, even hiring key Imagination staffers along the way.

InvenSense, a maker of motion sensors, relies on Apple for 40 percent of sales. In 2016, the company’s chief financial officer predicted a pullback from a mystery customer — presumed to be Apple. Investor’s Business Daily predicted sales would “topple” and within months InvenSense sold itself to a Japanese electronics company.

Japan Display, which gets 54 percent of sales from Apple, has become the latest to field questions from investors about whether it has been “shut out of Apple’s fortunes,” alongside Dialog Semiconductor (74 percent of revenue comes from Apple).

Speaking generally about Apple’s hardware suppliers, here’s what former Apple engineer Bruce Tognazzini told CNBC this week:

“What Apple does — and it’s a very deliberate strategy — is they line up enough components so that no matter how much sales run away, they are not going to run out of parts. And then, when they get to the point where they have a clearer picture of what the maximum number of sales will be, they cut back on their orders. This not only ensures they always have the parts they need, but it also ties up production capacity and keeps these companies from offering that capacity to other cell phone companies. So it’s kind of a double win for them.”

It’s not just smaller companies. Chipmaker Qualcomm gets 10 percent of revenue from Apple. After working harmoniously together for years, the two companies are in the midst of an exhaustive legal dispute over royalty payments, patents and contracts.

Qualcomm has many reasons to be concerned, including this one: As of Friday, Counterpoint Research estimates that Apple is now the top global smartphone system-on-a-chip provider — second only to Qualcomm.

Qualcomm declined to comment and Apple didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Hardware companies aren’t alone in tying their fortunes to Apple. Mobile game developers don’t have many places to go for distribution, with Apple and Google having largely cornered the market.

Apart from collaborations like Super Mario and Swift Playgrounds, Apple doesn’t stamp its name on too many games, turning instead to third-party developers to supply the entertainment that fills the App Store.

There’s plenty of money to be made. On Christmas day alone, consumers spent $158 million on mobile games, according to data from Sensor Tower. But gaming is also a hit-driven industry, fueled by fads like FarmVille, Pokemon Go and Flappy Bird.

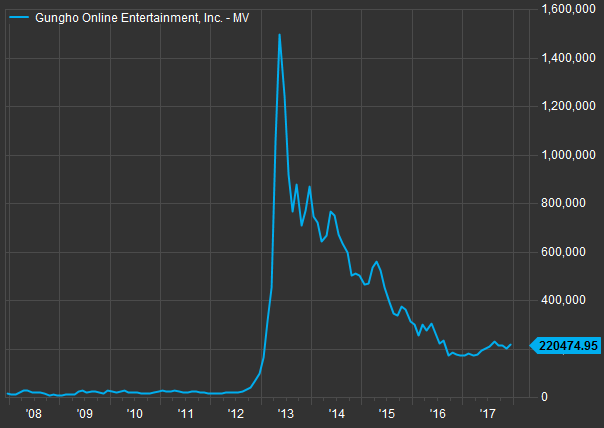

GungHo Online Entertainment, which gets 54 percent of its revenue from Apple, is a prime example of the risk.

Source: FactSet

Japanese tech mogul Masayoshi Son partnered with Apple to bring the iPhone to Japan in 2008, after practically banging down Steve Jobs’s door to propose a partnership with SoftBank. But it was Taizo Son, his brother, who founded GungHo (SoftBank owned a significant stake until 2016).

The Son brothers have a history of working together, dating back to launch of Yahoo Japan, and both men went on to become billionaires.

GungHo had been in the gaming business since 2002, but it was the launch 10 years later of “Puzzle & Dragons” on iOS that was the runaway success, becoming one of the world’s best-selling games.

But it didn’t last. GungHo’s sales and profits have slowed in recent years. After saying in 2014 that it wanted to be number one in mobile gaming, SoftBank abandoned that strategy last year.

“It’s (a) bit like running a bar,” one Japanese game maker told Bloomberg in 2015. “You’re always on, hustling to get the customers in and to keep them happy. Otherwise you have no business.”

Source: FactSet

Source: Tech CNBC

These 36 companies live and die by Apple