IN JUST a few short years Spotify has evolved from bête noir of some of the world’s most prominent recording artists to perhaps their greatest benefactor. The Swedish company transformed the way people listen to music, and got them used to paying for it again after digital piracy had crippled sales. Global revenues from music streaming, which Spotify dominates with 70m subscribers, more than tripled in three years, to an estimated $10.8bn last year, for the first time surpassing digital and physical sales of songs and albums.

But if it is earning billions for others, Spotify is losing money for itself—with an operating loss of nearly $400m in 2016—because it pays out at least 70% of its revenues to the industry, mostly in royalties. As it prepares for a “direct” listing on the New York Stock Exchange (see article) it must convince investors that it has a path to profitability. Some reckon it can find one, but only at the expense of the labels it has enriched: by paying them less in royalties; by getting them (and others) to pay for promotions and data services; and even by competing with them directly, by making its own deals with artists. In other words, Spotify may only be able to make money by reshaping the industry yet again.

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

Why commodity prices are surging

-

Why a judge’s injunction on DACA is unlikely to stand

-

Teenagers are becoming much lonelier

-

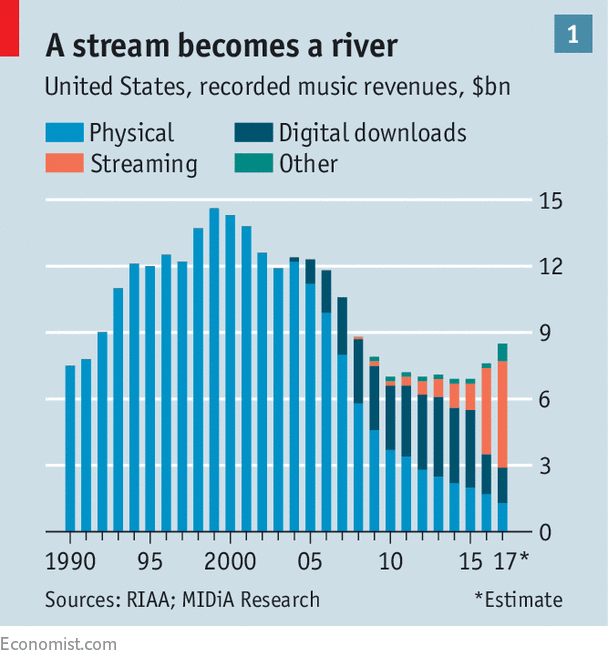

The Supreme Court considers the scope of automobile privacy

The economics of recorded music had shifted twice in the internet era before streaming came along, first owing to illegal file-sharing services such as Napster, then because of iTunes from Apple, which broke up the album. Retail music sales in America plunged by almost half, from a peak of $14.6bn in 1999 to a low of $6.7bn in 2014 (see chart 1). Spotify, which had launched its streaming application in 2008, was only a minor source of revenue but a major target of artists who believed they would never make money earning a fraction of a penny per song streamed.

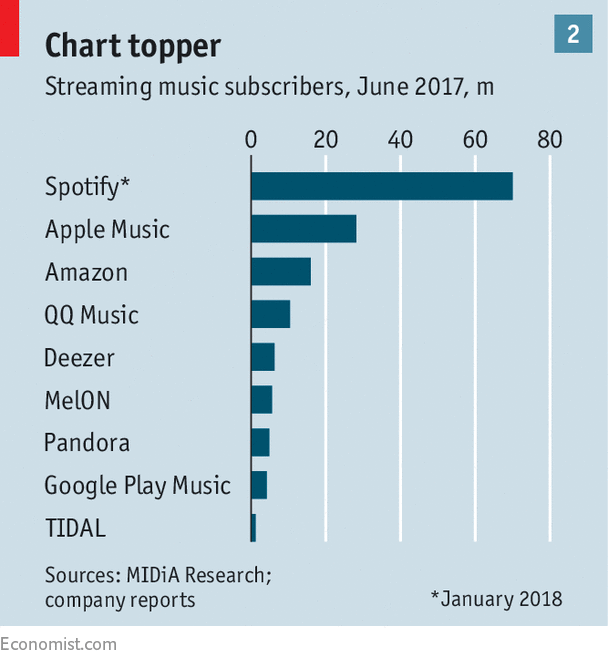

But Daniel Ek, the founder of Spotify (pictured), has long argued that the virtues of streaming would be manifest only when it achieved scale. That has begun to happen. In addition to Spotify’s subscribers who pay $10 a month (at least 70m more use its ad-supported free service), Apple Music has 30m subscribers and other music services have at least 70m more, according to MIDiA Research, a consultancy (see chart 2). Songs from the most popular artists now routinely surpass 1bn streams on subscription services—“Shape of You” by Ed Sheeran was Spotify’s top track in 2017 as of early December, with 1.4bn streams. On average a billion streams on subscription services brings in about $7m for big labels, with perhaps $1m of that going to the artists. Another pot of money goes to songwriters and composers.

With a big and widening lead over its competitors, Spotify has quickly become the industry’s most important distributor. Redburn, a research firm, estimates that in the first quarter of 2017 Spotify accounted for 17% of the $5bn in revenues taken by record labels, and its share is growing. That gives it several points of leverage that could help it turn around its operating losses.

Spotify’s most obvious power is its ability to make stars via its playlists and recommendation algorithms, much as radio DJs used routinely to do with simple airplay. Spotify has more than 2bn playlists; most of them are made by users themselves, but Spotify’s own curated lists attract millions of followers. Redburn reckons that up to 20% of streams are via one of Spotify’s own playlists. AWAL, an independent label run by Kobalt, a music-services company, says that getting on a Spotify playlist boosts a music act’s streams by 50% to 100%. Spotify would have to be careful how to monetise this clout, lest it be suspected of charging for a place on its playlists. But last year it did begin testing “sponsored songs” on its free service.

Another source of power for Spotify is its granular data on listening habits, ranging from where songs are listened to most and at what times, to what other acts a certain song’s listeners will also tend to like. Spotify provides a lot of data at no charge to industry players, some of which either it must do (for calculating royalty payments) or considers wise to do.

Mr Ek says making data freely available helps artists use the platform better, which in turn benefits Spotify. Its data are already used by labels, artists, promoters and ticket sellers in planning album releases, artist collaborations and concert tours. But analysts believe that, as Spotify gets bigger, it can do far more with its data and extract a good price—from promoters of live events, say, as well as ticket sellers.

The streaming service’s most intriguing point of leverage is that it could use these advantages to become a recorded-music label itself, working directly with artists. Matthew Ball, an analyst, argues that Spotify is sure to start cutting deals with artists in which it pays an upfront guarantee and promises a percentage of streaming revenue that is much smaller than it pays labels, but far more than artists get now.

The maths for these sorts of deals may be simplest for established artists, for whom performance is most predictable (though many will use their clout to get better deals with their existing labels). But with its data and playlist advantages Spotify can identify, elevate and theoretically sign contracts with up-and-coming artists, too. The channels that the labels knew so well, such as radio and record stores, have diminished in importance: “Breaking artists is one of the most important things labels do but it is becoming harder than ever,” says Mark Mulligan of MIDiA.

Becoming a label will not happen soon, partly because it would infuriate the incumbents who supply most music. But the growth of Spotify’s core business has come at a cost that is hard to ignore. Its royalty payments are a built-in, large expense. (Some rights-holders are clamouring for even more; in December Wixen Music Publishing sued Spotify for $1.6bn.) Competition from other paid streaming services mean it is hard for it to raise its own prices. To fund itself Spotify raised $1bn in debt in 2016 under terms that allowed two of the lenders, TPG, a private-equity group, and Dragoneer, a hedge fund, to convert to equity at a discount that increased with time, making an early public listing desirable. As long as its losses mount, it will seek other ways to turn a profit.

That threat gives the labels an incentive to accept lower royalty payments from Spotify. They have another reason, too: Alphabet’s YouTube, a source of free listening for perhaps more than 1bn people a month, which generates far less in royalties than subscription streaming. By helping Spotify, the industry helps itself.

Spotify has indeed negotiated reductions in royalty payments in the past year, beginning with Universal Music Group, a division of Vivendi and the largest supplier of music to the service, which reportedly agreed to be paid 52% of revenues, down from 55%. Spotify struck similar deals with the other two big labels, Warner Music Group and Sony Music.

Still, big-label bosses have long been conflicted about the company that changed their industry (and in which they each have a small equity stake). Early on they were sceptical about whether Spotify would make them much money. Now they may worry they are creating a future rival, much as the Hollywood studios licensed their content to Netflix. For the first time in 20 years the music industry is growing strongly. The fight for who comes out on top may have only just begun.

Source: economist

Having rescued recorded music, Spotify may upend the industry again