FOR years the cost of rights to broadcast major sports in America and Europe has trended in one direction—up. This gravity-defying law shapes the economics of modern sport: as television operators bid ever more substantial sums, teams take in more revenue and star-player salaries (and transfer fees) climb higher. In 2017 that trajectory continued as broadcasters splurged on rights for Champions League football matches for 2018-21.

This year gravity is reasserting itself. Top-flight football rights are out for tender in two major European leagues—England and Italy—and are expected to be put up for sale this year in France and Spain, too. Analysts expect relatively small increases in pay-outs (though Spain’s La Liga boss predicts a 30% rise)—and possibly a decline in Italy. “The happy days are over,” says Claire Enders of Enders Analysis, a research firm.

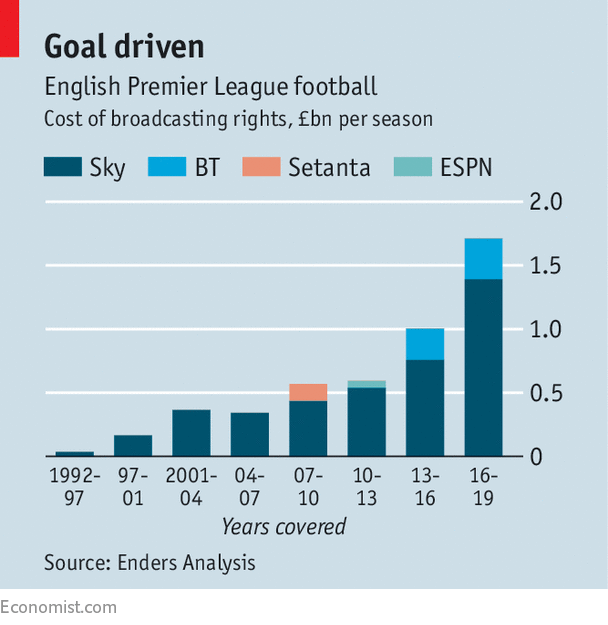

The chief problem is fundamental weakness at the bidding companies. In England, where bids for televising the Premier League for three years (from 2019) are due at the end of February, competition between BT and Sky Plc nearly trebled rights costs this decade to £1.7bn annually (see chart). But since the end of 2016 both have seen declines in subscribers to their high-priced packages, according to analyst estimates, as customers opt for cheaper internet-video services like Sky Now, Netflix and Amazon Prime. In December BT and Sky announced a cross-platform wholesaling agreement that will further depress bidding competition. (International TV rights sales will help boost the league’s coffers somewhat).

In France, Ligue 1 bosses had hoped for a significant bid from SFR, Altice’s French telecom business, to challenge market leader Canal+, owned by Vivendi, when they call for bids. The current contracts, worth €727m ($889m) annually, run to 2020. But Altice’s share price has lately plunged and the firm is selling assets; an expensive football bid looks unlikely.

In Italy, Mediaset Premium, one of two incumbent broadcasters (along with Sky), declined to bid for renewal last year, forcing Serie A to regroup for a new round of bidding, due by January 22nd. Mediaset, controlled by the Berlusconi family, has pledged to reduce football costs. Enders Analysis reckons it may go for a smaller package of games; Sky knows the market is soft. The league may struggle to match its current take of €990m per year.

In each market the value proposition of sport is in question. Football has been an important way to get consumers to sign up for TV bundles, yet high rights fees have dragged down earnings. Fans can get football highlights—ie, the goals—at no charge on social media, or watch pirated streams.

Might all that also portend trouble for the biggest sports media market, America? Disney’s sports channel, ESPN, has lost millions of subscribers in recent years due to cord-cutting (people dropping pay-TV). Viewership of pricey cable channels is in structural decline, as people spend more time on services like Netflix (or gawping at their phones). Live sport is still seen as a linchpin of pay-TV, a way to draw and keep customers, as it has been in Europe.

The appetite for sport in America is more diverse, which allows networks to build fuller schedules of fixtures, improving the appeal of pay-TV. The demand from viewers has been sufficient to sustain multiple bidders for rights, and to attract interest from new players such as Amazon. The contracts are longer, helping networks build long-term businesses (the next big rights renewal, for American professional football, is not until 2022). Still, Europe’s auctions suggest the economics of televised sport may slowly be recalibrated.

Source: economist

A weak market for football rights suggests a lower value for sport