GENERAL MOTORS reveals barn-sized truck at Detroit motor show. What else is new, you might now ask. But the launch on January 20th of the Chevrolet Silverado, a pickup that will go on sale at the end of the year, highlights a surprising turnaround for America’s largest carmaker.

The good news is not just the Silverado’s outsized margins, which are important for a firm that relies heavily on trucks—after Mary Barra, GM’s boss, gave an ebullient performance at an investors’ conference that coincided with the motor show, the release of GM’s quarterly results on February 6th are likely to include record profits. It is also that the money thrown off by vehicles such as the Silverado will help the firm navigate the tricky terrain that lies ahead of all the world’s big carmakers.

-

Some hotels charge visitors for bad reviews

-

Paul Romer quits after an embarrassing row

-

Music will miss irascible, unpredictable and prolific Mark E. Smith

-

Five English teams are among the ten highest-earning football clubs

-

Remembering Ursula Le Guin, the true wizard of Earthsea

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

One task is to ensure that their current business of selling vehicles with internal-combustion engines stays healthy. At the same time, they must prepare for a future of electric and autonomous cars (EVs and AVs), which threaten to up-end business models that have endured for a century.

Not so long ago, GM and its peers seemed to be on a path to extinction. Technology firms such as Alphabet, Uber and other pushy newcomers had started a race to develop software that would control driverless cars and to offer ride-hailing and ride-sharing services that are expected to thrive at the expense of car ownership. In April 2017 GM’s market value was overhauled by Tesla’s, a firm that makes just tens of thousands of flashy EVs a year, compared with the millions of vehicles rolling off GM’s production lines.

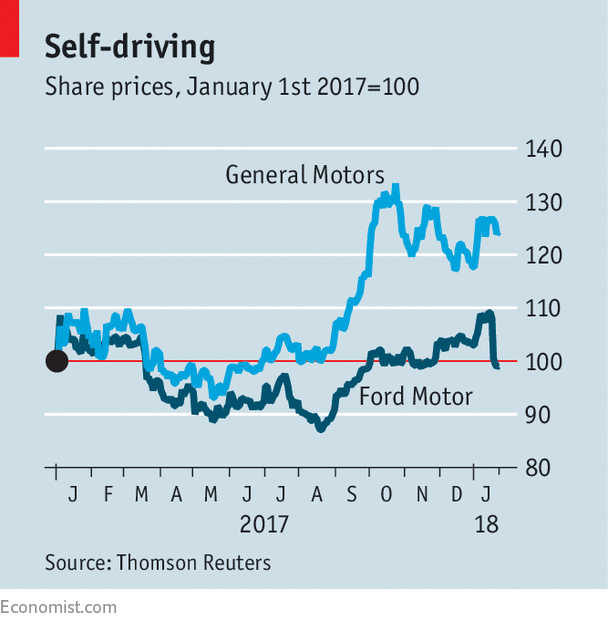

Sentiment has changed dramatically. Since April GM’s share price has surged by 28%, giving the firm back the lead. By contrast, Tesla has struggled with the nuts-and-bolts of carmaking. Production-line problems have hampered a big roll out of its mass-market Model 3. Analysts at Barclays, a bank, say that GM is more “evolving mammal than…dying dinosaur”.

One reason for the reversal of fortunes is that GM has convinced investors that its current business is in fine fettle. The cash generated by the Silverado and a range of new pickups will help pay for big investments in EVs and AVs. It does not hurt GM’s case that Ford, its main rival in Detroit, is struggling (see chart). Jim Hackett, a new boss brought in because of his technology know-how, oversaw a lacklustre relaunch in October that was sketchy on Ford’s vision for the future of transport services. On January 24th the firm reported disappointing quarterly results, dashing hopes for quick improvement.

In contrast, GM is already well on the way to reshaping itself. For starters, it has diverted resources to where it is a market leader. It has got rid of unprofitable businesses around the world, a process that culminated in a decision last March to sell Opel, its loss-making European carmaker, to France’s PSA. At the same time, GM has invested heavily in new pickups, such as the Silverado.

Cadillac, GM’s premium brand, may look like an exception to this happy rule. Sales of just 350,000 cars in 2017 puts it far behind its German rivals. Yet sales have doubled since 2010 and it has grown faster than any of them in recent years. Although the firm does not disclose the information, analysts at Morgan Stanley reckon that Cadillac could be worth $13bn, around 20% of GM’s current value. Johan de Nysschen, Cadillac’s boss, admits he runs a “challenger brand”, but sniffs an opportunity. The upheaval created as carmakers grapple with new business models means that “everyone has to start again”.

The most important reason for GM’s comeback, though, is its success in convincing investors that it is a leader not just among established carmakers, but among tech firms, too. It has rapidly accelerated from the position of an also-ran in the field of autonomous vehicles to apparent leader. A scorecard issued annually by Navigant, a consultancy, puts GM ahead of the AV pack of carmakers and tech firms, with Alphabet’s Waymo in second place.

That GM is ahead of Silicon Valley’s risk-takers may seem surprising. But earlier investments, which were once looked on with scepticism, seem to be paying off. Alan Batey, GM’s president for North America, points to the manufacturing of mass-market long-range EVs, where the firm has a lead. The Chevy Bolt, the world’s first such vehicle, has been on sale for over a year, beating Tesla’s Model 3 and the new Nissan LEAF to market.

The Bolt is supposed to be the basis for an ambitious autonomous ride-sharing business. On January 12th GM announced the latest version of its Cruise AV, a Bolt-based robotaxi without a steering wheel or pedals. GM plans to use it to launch a commercial scheme in several cities, starting next year. Rival tech firms and carmakers are only running, or are planning to launch, small test projects.

Revenge of the robotaxis

When GM paid $1bn in 2016 for Cruise, an artificial-intelligence startup, many analysts wondered whether it was throwing away money. But the marriage of cutting-edge technology and large-scale manufacturing seems to be paying off. The carmaker has learned to be more nimble; Cruise has picked up how to make its fiddly technology robust enough for the open road. As a result, GM can now mass-produce self-driving cars, says Dan Ammann, second-in-command to Ms Barra. Scale will help steeply to reduce the cost of sensors, which are the key components of an AV.

The firm is being rewarded because, unlike other carmakers, it has assembled all the parts of the puzzle you need to build new transport services, says Stephanie Brinley of IHS Markit, a consultancy. But even if GM is no longer a dinosaur, risks remain. In particular, it may be too bullish in its estimate of the market for robotaxis and it may be placing too much faith in the benefits of being the first to market.

The company expects demand to expand quickly. Costs of ride-hailing services, it predicts, will fall from $2.50 a mile now to about $1 as the main expense—the driver—is eliminated. In America alone it would be able to tap a market worth around $1.6trn a year (representing three-quarters of all miles travelled) as drivers are lured from their cars to robotaxis. But what Mr Ammann calls this “very big business opportunity” comes with an inconvenient corollary. As car buyers become car users, GM’s legacy business supplying vehicles to drive will decline accordingly.

Critics think that GM may have accelerated too swiftly and that it will have to endure years of losses before robotaxis take off. Even if things move fast, points out Berenberg, another bank, GM may not be the one to benefit. The main constraint in growing a ride-hailing business now is acquiring drivers. But when these are eliminated, capital will be the only limit. And that could mean huge fleets of robotaxis chasing passengers, forcing prices down. Riders may then choose a brand they recognise, such as Uber and Lyft, rather than Maven, GM’s ride-hailing business.

If so, being first would confer little advantage. And yet, if carmakers do not want to accept their fate passively, they have little choice but to remodel themselves. The outsized Silverado and the sensor-packed Cruise AV show that GM has the present in hand—and that it is at least doing its best to safeguard its future.

Source: economist

GM takes an unexpected lead in the race to develop autonomous vehicles