A YOUTUBE video featuring a woman sporting a gold watch and driving a convertible, which has been viewed online nearly 5m times. A social-media “influencer” with more than 11m followers on Instagram posting photos of herself wearing the same timepiece. A limited flash sale of the watch on Net-a-Porter, a website.

Purveyors of pricey jewellery and watches have been slow to embrace things digital. But last year’s social-media campaign to relaunch Panthère, a watch made by Cartier, a French jeweller, is evidence that they are waking up to the power of the online world. On January 22nd Richemont, a Swiss luxury conglomerate that counts Cartier among its brands, offered to buy the shares it does not already own in Yoox-Net-a-Porter group (YNAP), a leading luxury online retailer, for €2.7bn ($3.3bn). Although the deal still faces hurdles, it is likely to go ahead.

-

Five English teams are among the ten highest-earning football clubs

-

Remembering Ursula Le Guin, the true wizard of Earthsea

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

A severe case of “truth decay”

-

Britain’s statisticians are at war like never before

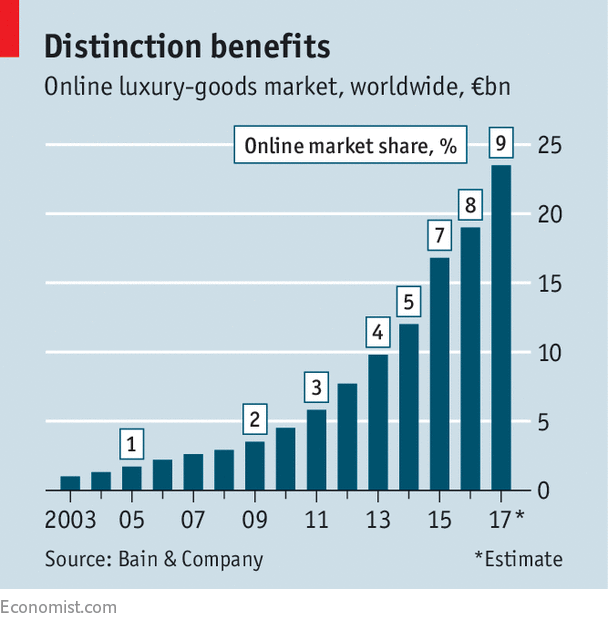

The days of double-digit growth in the luxury industry are gone—it grew by 5%, to €1.2trn, last year. Watches, in particular, have had a rough time. Chinese demand collapsed after an anti-corruption crackdown; inventory languished, unsold. Last year Richemont’s revenues dropped by 4%, to €10.6bn. But online sales of personal luxury goods have continued to rise: they now account for 9% of the total (see chart). Bain & Company, a consultancy, reckons that they will reach 25% by 2025.

Online sales of “hard luxury”, such as watches and jewellery, lag: they account for just 5% of digital revenues. But that is up from almost nothing a decade ago, and is predicted to reach between 10% and 15% by 2025. And even if purchases are made in physical stores, buying decisions are increasingly made online: 68% of millennials’ luxury purchases are “digitally influenced”, according to EY, a consultancy.

Small wonder that Richemont wants to expand its footprint online. Last year the group hired a chief technology officer, as part of a management restructuring which also did away with the role of CEO. It was an early investor in Net-a-Porter, which it merged in 2015 with Yoox, another e-commerce firm; it kept a 50% stake in YNAP, the resulting combination. The hope is that owning YNAP outright will allow Richemont to learn things about the online world that it could not with a stake alone. It would also increase the Swiss firm’s exposure to “soft luxury”, such as clothes and bags, a segment in which the firm has struggled, notes Melanie Floquet of JPMorgan Chase, a bank.

For YNAP itself, the deal promises added investment at a time of intensifying competition. Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH) has launched its own online platform, 24 Sèvres. Farfetch, another luxury e-tailer, is planning to float. Claudia D’Arpizio, a partner at Bain, suggests that Amazon, an online giant, could eventually disrupt the luxury market, too.

Not everybody is convinced a takeover of YNAP is needed. It is like buying an airline to go on holiday, says Luca Solca of Exane BNP Paribas, another bank. And the deal is not without risks. One is whether Federico Marchetti, YNAP’s boss, will indeed stay on once he has sold his 4% stake (he says he will). Ms Floquet also worries that the lack of a chief executive could lead to feuds within the management.

Such concerns do not seem to bother Johann Rupert, Richemont’s founder and chairman. In a statement on the offer he mentioned how, a century ago, Alberto Santos-Dumont, a famous aviator, complained to his friend, Louis Cartier, about the difficulty of checking his pocket watch while flying. Cartier listened, and—eureka!—the wristwatch was born. Full ownership of YNAP should, Mr Rupert seems to reckon, allow Richemont to listen to its customers, in person or not.

Source: economist

Richemont, the world’s second-biggest luxury firm, bets on digital