There is no set definition of a market melt-up. But it’s fair to say that we’re in one, or close.

If a melt-up is a sharp upward acceleration in stock prices from already-high levels with few pauses or pullbacks along the way and a rush of public enthusiasm, that roughly describes today’s market.

When some market watchers started talking about the chance of a melt-up to come a few months ago — cited in a column here back in October — some of the responses were, effectively, “Hasn’t 2017 been one big melt-up?”

No, the steady rally for most of last year was too well-behaved along too gentle a slope. The action since then has been more of a melt.

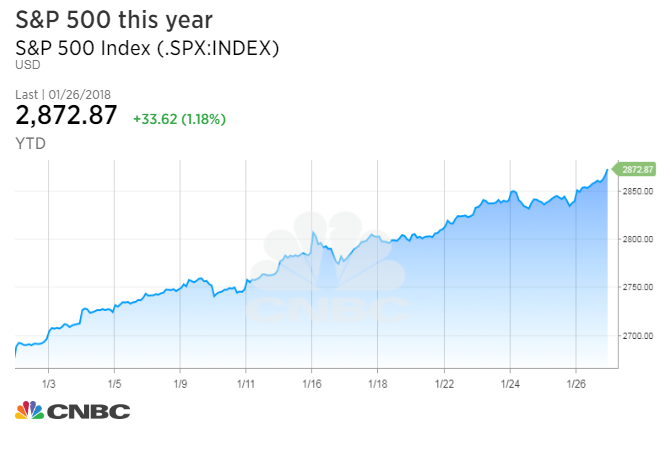

The S&P 500 is up 7.5 percent over 18 trading sessions so far in 2018, up more than 18 percent in five months, 26 percent from a year ago, 38 percent since the November 2016 election and nearly 50 percent from two years ago.

Naturally, Wall Street market strategists are trying to define a melt-up using some statistical standard, because that’s what they do, and because their fund manager clients keep asking, “Is this the melt-up?”

Chris Verrone of Strategas Research Partners suggests the threshold for a melt-up is a six-month rally that ranks in the top five percent of all such periods — right now that means a 21 percent surge. Not quite yet, but if the S&P adds about 3 percent in the next three weeks, it will qualify.

Jeff de Graaf at Renaissance Macro Research sets a slightly higher bar: Up 50 percent over 18 months. The market’s not there yet, but another 9 percent rise by the end of April would check off that box.

And Tom Lee of FundStrat says the market has already gone “parabolic” in January, accelerating to a 7-percent monthly rally pace from 2 percent per month the prior four months and 1.24-percent a month from January through August. Lee counts only six prior years when January went nearly vertical as this one has.

Source: Fundstrat

It probably makes sense to note that describing a market move as a melt-up is not a put-down. Some bullish investors bristle at the term, feeling that it implies something artificial or fleeting or unmoored from reality,

Really, melt-up just describes the pace and persistence of a rally at a time when the price appreciation seems to be feeding on itself. Think of it as the obverse of a market meltdown: There are almost always solid underlying fundamental reasons for a nasty market decline, but when the bad news and fear become saturating and the market’s scary freefall itself begets more selling, that’s the meltdown, or downside overshoot phase.

The thing is, meltdowns are more concentrated moments of panicky liquidation and tend not to last long; a melt-up can be a more prolonged phase of good economic news and swelling risk appetites feeding on themselves.

Studies of what happens after a melt-up phase demands that investors try to achieve F. Scott Fitzgerald’s definition of a first-rate intelligence: “The ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”

The first idea is that the stock market is comically, almost grotesquely extended to the upside after this near-ceaseless ascent as speculative behavior is heating up and valuation support is waning. The laws of financial physics say this can’t persist for much longer.

The second idea is that whenever the market has behaved like this in the past, it reflected abiding underlying strength and there was almost always substantial further upside ahead – often with tough downside shakeouts along the way though.

Market stat keepers tell us the S&P 500 has almost never been as “overbought” as it is today, in terms of the angle of its climb relative to a longer-term trend. This month, the S&P 500 has been compounding at a 125-percent annualized rate. Analysts’ pace of increased-earnings revisions is nearly off the charts, usually a sign that improving fundamentals are getting fully priced in.

Ned Davis Research’s crowd sentiment poll never showed more collective bullishness. The S&P is in its longest streak without a 3 percent pullback, near the longest run without even a 1 percent dip and has gone 99 days without as much as a 0.6 percent daily loss – by far a record.

The careful investor who’s looking at all of these superlatives and rare extremes then asks what typically happens next? And the answer comes back, “Usually more gains for a while, often with a choppier ride.”

This is what the melt-up chroniclers such as Lee and Verrone and all the rest repeatedly find in the historical record: Even if we’ve seen the peaks in market momentum, investor optimism, investor fund flows and upside earnings revisions, the indexes themselves have rarely topped for good until some time and distance afterward.

Retail stock-fund inflows are near a record level and online-brokerage volumes as a percentage of total market activity has gone vertical this year. This is the “all-in, things-are-good-and everyone-knows-it” period, the makings of a bull-market “overshoot.”

Bespoke Investment Group suggests any slight tremor from here could feel like a scary quake: “The longer we go without experiencing any declines of significance, it’s going to make the eventual decline feel exponentially worse when it finally happens…This means emotions will run extra high the next time a drop occurs, which could precipitate more selling than usual.”

All global asset markets are at some relative or absolute extreme: The dollar at multi-year lows, oil and bond yields exceeding the top of long-standing ranges, credit spreads near all-time tight levels and the valuation of stock to bond valuations at a seven-year high.

Even if the melt-up carries higher and the first reversal isn’t likely to be the “big one,” these markets could get more interesting soon.

Source: Investment Cnbc

Pros call the stock market's parabolic up move this year a 'melt-up' and they think it can keep going