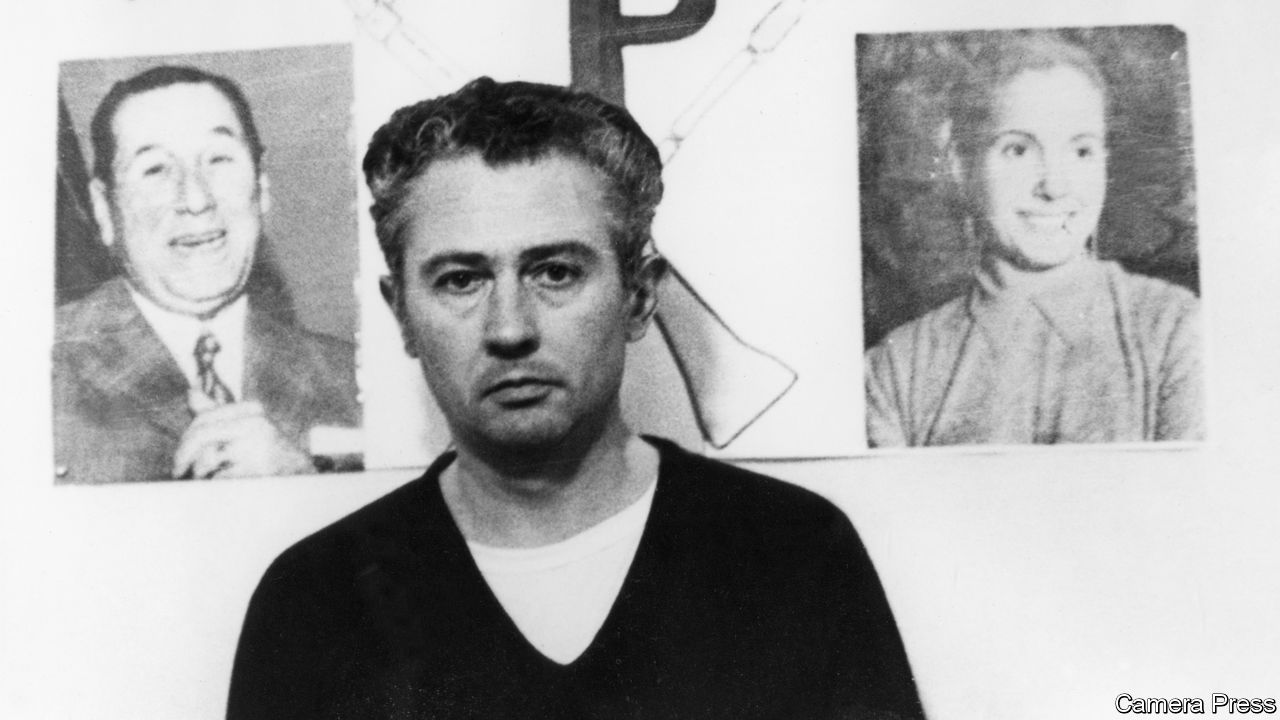

IN THE early 1970s, leftist guerrillas in Argentina discovered a lucrative new way to make money: kidnap millionaires. Panicking firms would agree to huge ransoms, more concerned with freeing their executives than driving down the fee. That was not just bad for businesses. It also became a textbook case of how poor negotiating can send future ransoms rocketing and attract new entrants to the kidnapping trade. In Argentina, this culminated in the payment of an undisclosed ransom in 1975 for the release of Juan Born, followed by a $60m ransom for his brother, Jorge. The latter figure, $275m in today’s money, is the highest ransom known in modern times.

One reason it marked a high point is the spread of kidnapping-and-ransom (K&R) insurance. This is involved in a minority of the $0.5bn-1.5bn thought to be paid out in ransoms each year, but the share is growing. Around three-quarters of Fortune 500 companies pay to cover some employees. Insurers reimburse the ransom and, at least as importantly, provide seasoned “crisis management” experts to help with negotiations. The best can get a ransom down to 10% of the initial demand. They can also calm criminals who may consider harming hostages to induce distraught relatives to pay up. In kidnappings motivated by money, a hostage’s risk of death during negotiations is 9% without K&R insurance, but just 2% with it, according to Anja Shortland, who is writing a book about kidnapping insurance. Kidnappers rarely know if a victim is insured.

-

“Heavenly Bodies” mixes metaphors at the Met

-

Olga Tokarczuk has finally found major recognition in English

-

Jordan Peterson on modern liberalism

-

Does the screen image of women need to change?

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

How California could split up

Even without blood spilled, kidnappings ruin lives. Victims are often traumatised. A ransom can wreck a family’s finances. Kidnappings also keep companies and charities out of places in need of investment and help. K&R insurance has evolved to lessen these harms. Coverage includes legal liability for companies and counselling for survivors. Many rich families in countries such as Nigeria and the Philippines also take out coverage. However, employees with K&R insurance are forbidden from finding out they have it, for fear of encouraging more kidnapping if word gets out. Insurance is usually invalidated if its existence is confirmed.

Raw deals and ordeals

On a sunny day in Mexico City, Carlos Seoane of Seoane Consulting Group, a crisis-management firm, recalls how his hands shook the first time he listened in on a negotiation as a trainee. Some 116 kidnappings later, that no longer happens, he says: “Now I am made of ice.” Mexico’s kidnappers once targeted the ultra-rich. In recent years the trade has “democratised” to strike the middle class too, he says.

Kidnappers may search for victims on dating platforms, asking questions that reveal whether they have any money. Mr Seoane recalls a case where kidnappers turned up at a pig farm and asked to buy 20 pigs. A man identified himself as the owner of the swine, and was immediately grabbed. Random kidnappings on impulse have become more common. So have “express” kidnappings, where the victim is whisked to a cash machine to withdraw money, and “virtual” ones, where people are tricked into thinking a relative has been nabbed. As is usual for crisis-management firms, Mr Seoane’s works exclusively with a single insurance provider.

Insured negotiations are almost always carried out by family members, with calls recorded and trained negotiators giving advice. In countries where kidnaps are common, the police are seldom involved. Kidnappers expect to receive a lower ransom than they originally demand. If a family agrees on a price too soon, most kidnappers sense the chance to up their demand. Paying more money does not make the hostage safer, says Mr Seoane.

If negotiators are not careful, they risk sending ransoms spiralling, as in Argentina. In many countries the media refrain from publishing information about the size of ransoms for fear of attracting more criminals to the business. The average ransom paid to free ships captured by Somali pirates doubled between 2009 and 2011. Paying out generous ransoms hits everyone in the insurance industry, and those they cover. It may lead insurers to attach conditions to coverage, such as employers imposing a curfew or a requirement to hire private security.

To prevent bad negotiations wrecking their business, insurers have clubbed together. All of the 20 or so who underwrite and reinsure K&R have syndicates in Lloyd’s, a marketplace for insurance in London, says Ms Shortland. Information-sharing between underwriters enables them to price K&R coverage in different parts of the world. If one crisis-management firm is negotiating irresponsibly, underwriters who employ them risk being kicked out of the Lloyd’s club, cutting off their access to pricing information.

The system has worked well. The cost of K&R insurance has fallen by half in the past decade, says one underwriter, bringing new customers into the market. But the popularity of K&R insurance itself could create a moral hazard. People in kidnapping hotspots may be targeted on the assumption that insurers will pay the ransom. Kidnappers would then have little reason to compromise.

Source: economist

How kidnapping insurance keeps a lid on ransom inflation