BESIDE a serene lake in Switzerland sits a modern glass building called the Cube. Wide-leafed tobacco plants grow in the lobby. In one room machines that can “smoke” more than a dozen cigarettes at a time dutifully puff away, measuring the chemicals that consumers would inhale. The research centre is run by Philip Morris International (PMI), which sells Marlboro and other brands around the world. The facility’s purpose is not to assess the risks of smoking, but to determine whether this huge cigarette-maker might get out of selling cigarettes altogether.

André Calantzopoulos, PMI’s chief executive, talks about moving to a “smoke-free future”, with the firm’s business comprised entirely of alternatives to cigarettes. “We are crystal clear where we are going as a company: we want to move out of cigarettes as soon as possible,” he says. Mr Calantzopoulos has the boldest goals in this regard, but he is not the only tobacco executive to tout a new direction. Nicandro Durante, chief executive of British American Tobacco (BAT), PMI’s main rival, says that investing in lower-risk products is a win for shareholders, consumers and society.

The idea that large tobacco companies might advance public health seems almost laughable. They still clash frequently with courts and regulators. It was only in November, after more than a decade of resistance, that companies began to comply with a landmark ruling from an American court in 2006 stating that they had worked for decades to deny the risks of smoking. Since November 26th firms have had, for example, to include wording in adverts that they “intentionally” designed smokes in a way that made them more addictive.

Yet the firms also make safer alternatives. E-cigarettes have been around for a while; a newer invention are products that heat tobacco without producing all the deadly stuff that comes from burning it. PMI sells one such “heat not burn” (HNB) product, called IQOS, in nearly three dozen countries, including Italy, Switzerland, Japan, Russia and South Africa. Britain’s Committee on Toxicity recently found that people using HNB products are exposed to between 50% and 90% fewer “harmful and potentially harmful” compounds compared with conventional cigarettes. Public Health England, a government agency, says there is a large amount of evidence that shows e-cigarettes, too, are much less harmful than smoking, by at least 95%.

Mr Calantzopoulos wants two-fifths of PMI’s revenue to come from IQOS, e-cigarettes and other safer products by 2025—and “hopefully much more”. Much will depend on regulators. In America, the world’s second-largest tobacco market after China, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) plans to begin a regulatory process to get companies to reduce nicotine in cigarettes, rendering them less addictive, while making it easier for the firms to introduce safer products.

Scott Gottlieb, the FDA’s commissioner, says that change may be the single most important step he can take to advance public health. Smoking kills more Americans than car crashes, murder and drugs combined. Early in 2018 PMI may get the FDA’s approval to sell IQOS in America. PMI would license the product to Altria, which sells Marlboro in America. A few months later IQOS may also become the first tobacco product the FDA allows to be advertised as less harmful than cigarettes (using a rule from 2009). PMI has submitted more than 2m pages of evidence to that end.

Puff adders

All this puts the tobacco industry and those who attack it in an odd position. Companies are developing products that could save millions of lives each year, while still making an addictive product that is known to cause fatal diseases. Next to the Cube stands a PMI factory that can make up to 17bn cigarettes a year. Anti-smoking campaigners, including Vera Luiza da Costa e Silva, who leads the implementation of the World Health Organisation’s anti-smoking treaty, are particularly dismayed by firms’ attempts to stymie anti-tobacco measures in poor and middle-income countries.

Tobacco-makers have sued countries or threatened litigation over their rules to limit conventional smoking. PMI, for example, argued that Uruguay’s graphic warnings on cigarette packages violated the terms of a trade deal (a judge decided against the firm in 2016). BAT has a case pending in Kenya against its anti-tobacco laws. Even if a country wins in the end, tobacco firms’ resistance means that anti-smoking policies are usually delayed, both in the sued country and in others wary of starting legal battles. Thousands of new smokers might light up in the meantime. Tobacco companies also fight the one measure that really curbs smoking: sudden spikes in tax levied on cigarettes.

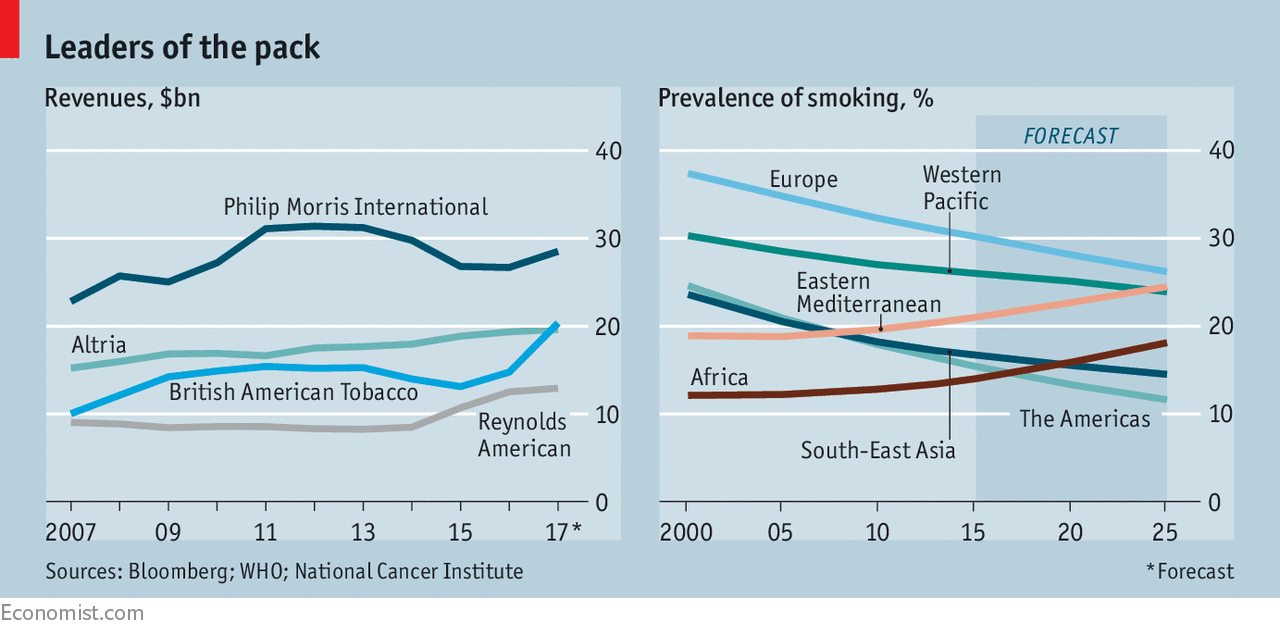

The business case for conventional cigarettes is clear. They remain wildly profitable. Matthew Grainger, an analyst at Morgan Stanley, estimates that the average profit margin on a premium cigarette can reach about 80%. Nor has the impact of regulation been all bad for the tobacco industry. In countries where advertising is banned, large companies save on marketing costs and young brands find it harder to challenge them. As smoking rates decline in much of the West, firms have been able to raise prices for cigarettes in rich countries while promoting smoking elsewhere.

New smoking products also promise to benefit Big Tobacco. The giants were late entrants to the e-cigarette market but caught up quickly by buying up popular brands and launching their own products. They now have around four-fifths of the market. E-cigarette sales doubled between 2014 and 2016, though still make up under 5% of total tobacco revenues. New products are also harder for rivals to replicate than conventional cigarettes. BAT points to $2.5bn of investments in new, lower-risk products since 2011; PMI has invested more than $3bn since 2008. Big companies also have the resources to seek regulatory approval for new products whereas smaller firms may struggle to do so.

How regulators around the world actually treat these products varies. The FDA is signalling receptiveness. Indeed, its proposed approach must set tobacco executives’ pulses racing, because the more restrictive part of the FDA’s plan, to reduce nicotine in combustible cigarettes, will take years to implement. That gives them time to continue making money from old products as they build up their less harmful business. The FDA has not finalised its rules, but they will probably include a phased restriction on nicotine: lowering levels too quickly might just boost the black market for cigarettes.

Outside America the industry faces a mishmash of conflicting rules. In Britain the Royal College of Physicians has said that e-cigarettes are a sensible, promising way to help smokers quit. Other regulators fear that e-cigarettes and tobacco-heating products will make the habit of puffing at a stick more normal again and serve as a first step for people to become addicted to real cigarettes. In 2016 a group within the World Health Organisation invited those who had signed its anti-tobacco treaty to “prohibit or restrict” e-cigarettes.

PMI hopes to influence the debate. In September the firm announced it would give $80m a year for the next 12 years to a new foundation to research ways to speed the shift away from tobacco, including through the use of lower-risk products. It has been met with scepticism. According to Dr da Costa e Silva, the foundation is part of a “long-established and sinister pattern of corporate chicanery”. “I recognise that we have a deficit of credibility and trust,” says Mr Calantzopoulos. “I’m not asking people to believe me—I’m asking them to verify what we are doing, including the science we produce.”

Part of the difficulty in judging the merits of alternatives to cigarettes, says Matthew Myers of the Campaign For Tobacco-Free Kids, an American anti-tobacco group, is that their traits vary wildly. A bubble-gum flavoured e-cigarette may attract younger users, for instance; an e-cigarette with too little nicotine will not sate a conventional smoker, so will not help him quit. Studies that group all e-cigarettes together may therefore be misguided.

Burning questions

To date most discussion has centred on e-cigarettes, but tobacco-heating products such as IQOS may eventually be a bigger market. PMI says that heating tobacco produces a sensation that many current smokers find more pleasing than an e-cigarette, but which is less dangerous than a real smoke. The company argues that IQOS and its successors will therefore be more effective than e-cigarettes in helping people snuff out their conventional smokes. In Japan, where about a third of men smoke, by the end of 2016, 70% of IQOS users had switched from conventional cigarettes and were using IQOS alone.

This debate is occurring against a changing landscape in the tobacco industry itself. In July BAT paid more than $49bn to acquire Reynolds American, America’s second-biggest tobacco company after Altria. Scale gives tobacco firms the ability to expand margins on conventional products, as well as more money to invest in new ones and sprawling legal teams to deal with shifting regulations. In buying Reynolds, BAT won access both to the American market and to Reynolds’ portfolio of e-cigarettes. The deal raised no concerns among antitrust regulators. Now many investment analysts expect PMI to buy Altria, which sells PMI’s portfolio of brands in America.

It was in part to quarantine its business from American litigation that PMI split from Altria. But that risk is fading. A merger would let PMI collect the full margins from IQOS in America and better compete against a beefed-up BAT. Mr Calantzopoulos denies that any such deal is in the offing. But investors in the firm may be in favour of one. If it happens, the world’s biggest multinational tobacco companies seem poised to save many consumers in future, kill millions of them in the meantime and, through multibillion-dollar mergers, become even more powerful. Put that in your pipe and smoke it.

Source: economist

Combustible cigarettes kill millions a year. Can Big Tobacco save them?