A DAY before the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) voted to rescind “net neutrality” regulations designed to ensure that internet-service providers do nothing to favour some types of online content over others, Ajit Pai, its chairman, tweeted a short video reassuring Americans. “You can still post photos of cute animals,” he says in it, posing with a dog. He also wields a light sabre, which prompted Mark Hamill, the actor who portrays Luke Skywalker in the “Star Wars” films, to criticise Mr Pai on Twitter for siding with giant corporations. Ted Cruz, a Republican senator, then asserted in Mr Pai’s defence that Darth Vader supported government regulation of the web; further jabs followed.

It made for a silly treatment of an arcane subject. But net neutrality is a serious business. The state of New York’s attorney-general said he would lead a multi-state suit against the FCC; in Congress Democrats and Republicans are expected to propose competing bills on the subject in 2018. Broadband and wireless companies such as AT&T responded to fears about their increased power by questioning whether internet firms like Google have too much. Google, Facebook, Amazon and other platform companies in turn put out statements in support of an open internet. So rather than end the struggle over how the internet is regulated in America, the FCC’s vote has intensified it.

-

Nationalism: further reading

-

The Economist’s playlist of national anthems

-

Foreign reserves

-

The Las Vegas Golden Knights are hitting hockey’s jackpot

-

Ryanair stops Christmas strikes, but at a cost

-

At 50, “The Graduate” still has much to say about youth

It may be years before it becomes clear what is at stake. The FCC’s action, taken on December 14th in a 3-2 vote with Republican members forming the majority, rolls back regulations adopted by the same body in 2015 when Democrats were in charge. The old rules were designed to ensure that all content online would be treated equally by companies such as Comcast and AT&T. These would be prevented from slowing down or “throttling” a service like Netflix and instead giving priority to another competing service.

Democratic officials, consumer activists and big internet firms argue that consumers will now experience different internets based on which broadband or wireless provider they use. If a service pays for faster access on a provider, which is called “paid prioritisation”, more consumers may see it; if another service does not pay, consumers may not come across it. Many cite the case of AT&T, which is trying to buy Time Warner, warning that HBO, a premium cable channel, could in future get into a “fast lane”. Some critics go much further, arguing that internet providers will in effect censor content they do not like.

Republicans note that if internet providers abuse their power, they will be punished by another regulatory body, the Federal Trade Commission (though its scope for taking action is much narrower than the FCC’s). The telecoms giants also argue that freeing them from regulation will encourage much-needed investment in broadband and wireless infrastructure.

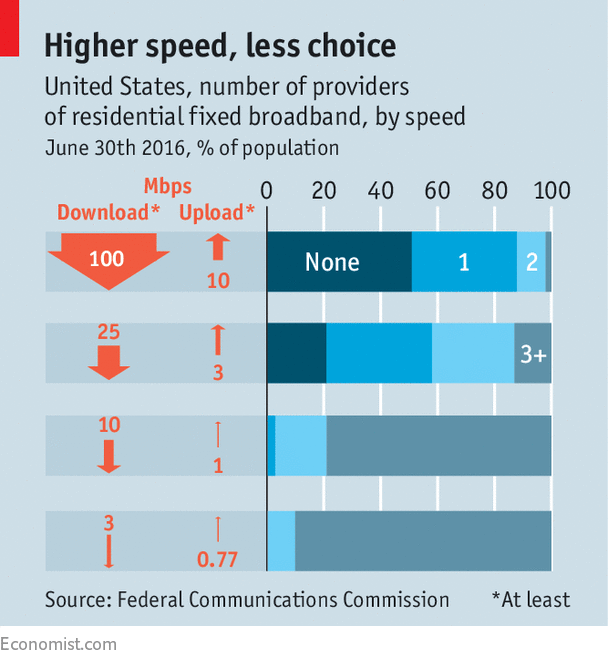

In the short run, says Kevin Werbach, a former FCC lawyer who backs net neutrality regulation, firms such as AT&T and Verizon “get that there’s this backlash so the industry is not going to intentionally be so stupid as to realise the worst fears that are out there.” If they are caught throttling rival services, they will rile consumers. If they raise prices on popular ones, they will lose customers (where there is a choice, that is—many broadband providers enjoy regional monopolies; see chart). If they move quickly to build “fast lanes” or “slow lanes”, they will hand ammunition to Democrats in Congress who support tough regulation. For now, then, telecoms giants are likely to concentrate on ensuring that, if Congress does legislate on the issue, softer regulations prevail.

Source: economist

A vote on “net neutrality” has intensified a battle over the internet’s future