AT AN investor briefing in 2015, Masayoshi Son, chief executive of SoftBank, flashed up a picture of a goose. The company is like the bird of legend that produces golden eggs, he explained. In his quest to encourage more laying, Mr Son has taken SoftBank well beyond its telecoms business. The firm also manages the world’s largest tech-investment fund, the $100bn Vision Fund, which has a slew of wealthy backers, including Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund and Apple.

Using both the firm and the fund, Mr Son has acquired stakes in tech companies at a frenetic pace, by one count opening his chequebook once every four days on average in 2017. Such shopping sprees do not come cheap. SoftBank is one of Japan’s most highly leveraged companies, with debt exceeding ¥15trn ($139bn), not least because of its purchase in 2013 of a controlling stake in Sprint, an American mobilenetwork operator.

-

Are programs better than people at predicting reoffending?

-

How gender is (mis)represented in economics textbooks

-

Sri Lanka’s president is struggling to keep his promises of reform

-

Chechnya moves to silence Oyub Titiev, a courageous critic

-

The Bayeux tapestry is an intriguing symbol of post-Brexit co-operation

-

The rise and fall of bitcoin

News reports this week suggest SoftBank is now hatching a plan to raise ¥2trn by floating 30% of its Japanese telecoms business, SoftBank Corporation, on the stockmarket later this year. (The company says that listing is one of the options it is considering but no decision has yet been made.) If the IPO went ahead, it would be Japan’s largest since SoftBank’s rival, NTT DoCoMo, went public 20 years ago.

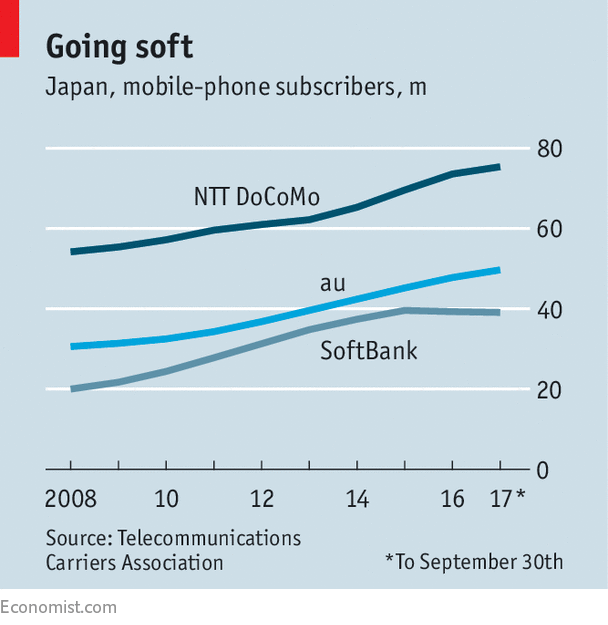

With 39m subscribers, SoftBank Corporation is the third-largest provider in Japan, catering to a quarter of the market. It is past the phase of straightforward growth. Prices came under government scrutiny in 2015, squeezing profits across the industry. SoftBank’s subscriber numbers have been flat; a new competitor, in the form of an e-commerce company, Rakuten, will further threaten market share. But the business still accounts for over two-thirds of the group’s operating profits.

Investors appeared to approve of the idea of a float, with SoftBank’s share price rising by 6% on the announcement. The IPO offers a way to raise capital without further straining the firm’s balance-sheet. But few expect that Mr Son will use the money actually to pay down much debt; some will probably go into topping up the Vision Fund, which has yet to close and which has raised $93bn of a planned $100bn. Mr Son has said before that he would like to run such a fund once every few years. The aim, Mr Son says, is to own bits of companies that will power the global race to develop ever more capable artificial intelligence. He has poured money into everything from driverless-vehicle technologies and e-commerce platforms to agricultural technology.

Mr Son may also be hoping that floating the telecoms business shrinks the discount on SoftBank’s shares. Its market capitalisation is less than the sum of its holdings—notably its 30% stake, worth $140bn, in Alibaba, a Chinese e-commerce giant. An IPO could make valuing the group easier, but it will remain a complicated structure. There is also a risk for minority investors in SoftBank Corporation, who could find themselves at odds with the majority-owner.

Even if investors in SoftBank approve of the idea, they will worry about whether the money will be well spent. With the Vision Fund, Mr Son is piling into a crowded tech market where valuations are frothy. And glittery though the investments may seem, not everything he touches turns to gold. His reputation as a dealmaker mainly rests on his early bet, in 1999, on Alibaba. Mr Son wants to plump the goose; shareholders can be forgiven for carefully inspecting the nest.

Source: economist

Masayoshi Son may raise yet more cash to pump into tech