IT IS usually considered quaint to predict foreign-exchange movements by reference to whether currencies are dear or cheap. Metrics such as The Economist’s Big Mac index, a lighthearted guide to exchange rates, hint at how far currency values are out of whack. But they are often driven further out of kilter by capital flows, by fear and greed, by the interventions of policymakers, and so on.

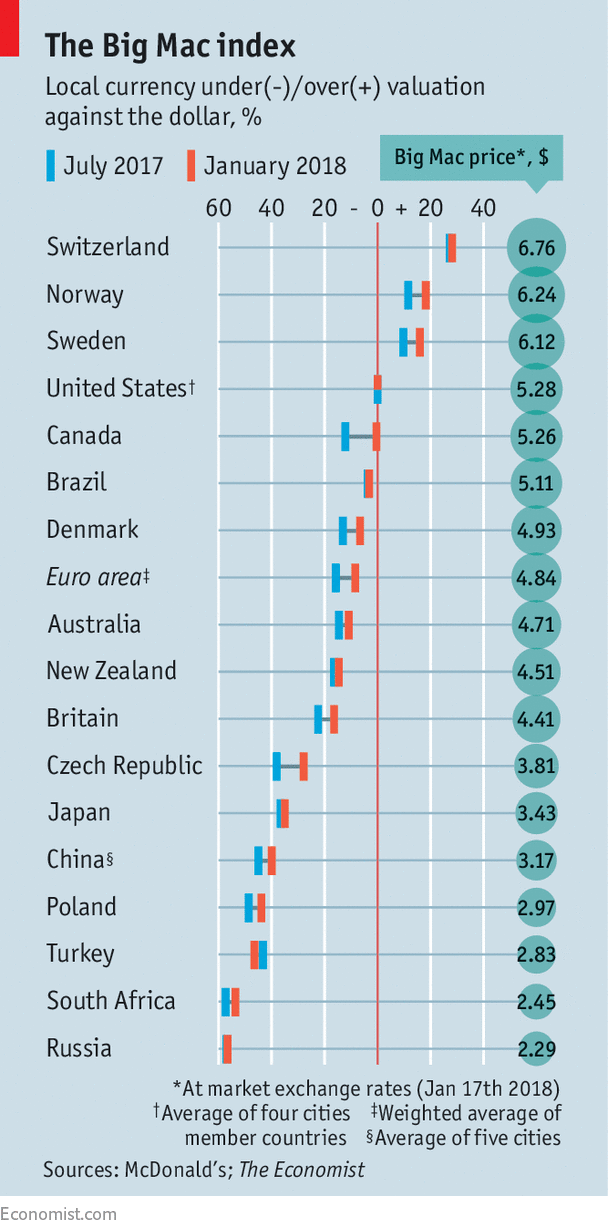

Since our last look at the index in July, cheap currencies have narrowed the valuation gap against the dollar—almost completely in case of the Canadian dollar (see chart). Fundamentals, such as fair value, seem (at last) to have greater sway in the foreign-exchange market.

-

Legacy airlines are facing new competitors on transatlantic routes

-

The Trump administration bars Haitians from visas for low-skilled work

-

Can a lawyer admit the guilt of a client who claims to be innocent?

-

Democrats pull off a surprise win in rural Wisconsin

-

Return of the Mac

-

A powerful dramatisation of the murder of Gianni Versace

The index is based on the idea of purchasing-power parity, which says exchange rates should move towards the level that would make the price of a basket of goods the same in different countries. Our basket contains only one item, but it is found in around 120 countries: a Big Mac hamburger. If the local cost of a Big Mac converted into dollars is above $5.28, the average price in four American cities, a currency is dear; if it is below that yardstick, it is cheap. The average cost of a Big Mac in the euro area (weighted by GDP) is €3.95, or $4.84 at the current exchange rate. That implies the euro is undervalued by 8.4% against the dollar, our benchmark. The last time we looked at burgernomics, it was almost 16% undervalued. The euro surged after Mario Draghi, boss of the European Central Bank, hinted at a conference in Sintra, Portugal, that the bank’s bond purchases might soon be curtailed. It was as if the foreign-exchange market suddenly woke up to how cheap it was.

Measured against a basket of currencies, the dollar still looks dear. Only in three countries (Switzerland, Norway and Sweden) do burgers cost more, based on current exchange rates. But that is not necessarily a sign that depreciation is overdue in these countries. The cost of a burger depends partly on untradable inputs, such as rent and wages, which are higher in the rich countries on the fringes of the euro zone. So the price of a meal may not be a good guide to how competitive a country is in markets for tradable goods. The Swiss and Norwegian currencies look dear, for instance, but both countries have big trade surpluses.

Among rich countries, only Britain’s and Japan’s currencies stand out as bargains. The pound is cheap for a reason— Brexit. But it might be harder for the yen to stay so cheap. The euro has shown that the merest hint of an end to easy monetary policy can prompt a sharp rally. The yen may have a similar “Sintra moment”, says Kit Juckes of Société Générale, a bank. For those who feel they have missed out on the euro at bargain-basement prices, there are other ways to bet on the burgeoning strength of the euro-zone economy. Poland and the Czech Republic have strong links to the euro area and robust GDP growth. The Polish zloty is undervalued by 44% against the dollar, and the Czech koruna by 28%.

The caveat that applies to Switzerland, Norway and Sweden applies in reverse to emerging markets, where rents and wages are lower than in the rich world. In general, currency gauges based on purchasing-power parity work best when comparing countries with similar income. That said, many emerging-market currencies do look cheap. The Russian rouble, for instance, is still 57% undervalued even after a big rally in the oil price. South Africa’s rand is almost as cheap. Eat hamburgers with Johannesburgers.

Source: economist

Our Big Mac index shows fundamentals now matter more in currency markets