THERE may have been a “Trump bump” in the stockmarket but the opposite has been true in currency markets. The dollar has steadily weakened and the administration does not seem too concerned about it. Steven Mnuchin, the Treasury secretary, said this week that

Obviously a weaker dollar is good for us as it relates to trade and opportunities.

-

The buck drops here

-

Why the genome of wheat is so massive

-

Northern Ireland notches up a year without a government

-

Donald Trump’s travel ban heads back to the Supreme Court

-

Sequencing the world

-

The Donald versus Davos Man

He qualified his remarks by saying a strong dollar reflects a strong US economy. Leaving aside his clear confusion (so does the dollar’s weakness mean the US economy is weak?), it is rare for any Treasury secretary to welcome a fall in the greenback.

Paul O’Neill, who held the position under George W. Bush, declared that

I believe in a strong dollar, and if I decide to to shift that stance I will hire out the Yankee Stadium and some rousing brass bands, and announce that change in policy to the whole world.

There are many reasons why politicians like to speak about a strong dollar. A decline in the currency tends to push up import prices, and thus inflation. The US has a big fiscal deficit, which it has to finance from abroad; foreigners won’t be keen on buying fixed-income securities in a declining currency. Ten-year Treasury bonds now yield 2.64%, up 15 basis points in the last month; the five-year yield is up half a percentage point in the last year.

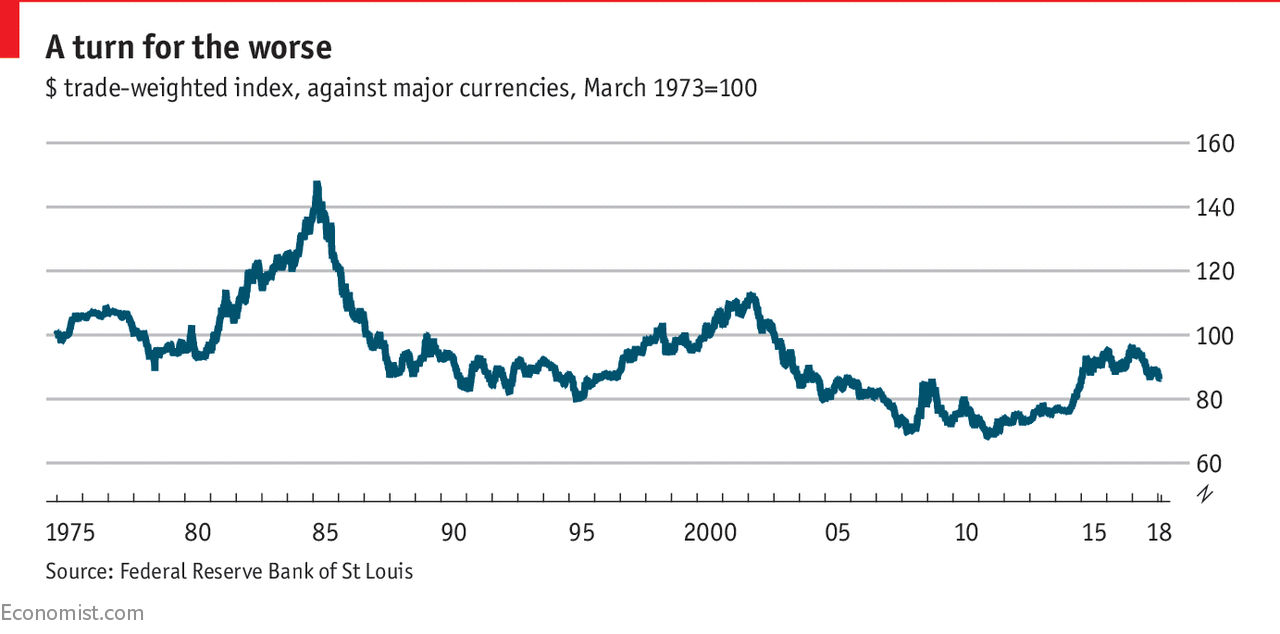

In the past, the dollar’s movements have often been seen as a vote of confidence in a particular president’s policies. In the late 1970s, the economic malaise under Jimmy Carter was followed by a rebound in Ronald Reagan’s first term (see chart). So big was the move that, in 1985, leading nations agreed the Plaza accord to drive the dollar back down. The next dollar revival was in Bill Clinton’s second term when the technology boom made US assets highly attractive. A decline under George W. Bush was followed by a couple of rallies under Barack Obama; the first in the depths of the crisis, as investors pulled money from the rest of the world in favour of the perceived safety of US assets, and a steadier rise in the early years of this decade.

The current fall, under President Donald Trump, is not spectacular by historical standards. A number of factors explain the shift. First, the world economy is recovering. So investors may be moving money away from the US and into Europe and emerging markets. Second, the recent tax-cutting package passed by Congress means that the US will combine a big fiscal deficit with a trade deficit; meaning its government needs financing from abroad. Under Reagan, the US also had a “twin deficit” problem but this prompted the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates sharply, attracting capital into the dollar; the current Fed is pushing up rates but only slowly. Third, the erratic pronouncements of the current president may be discouraging foreign investment; a Pew survey last year found a dramatic slump in the image of the US as seen from abroad. As yet, one of the bullish arguments for the dollar—that American companies would repatriate cash because of a change in the tax laws—doesn’t seem to be having any impact.

If Mr Mnuchin wanted to drive the dollar back up, what could be do? He could asked the Fed to intervene by using its reserves to back the currency, but that is unlikely. Alternatively, he could attempt to close the budget deficit but that would be a complete reversal of policy (the Tax Policy Center suggests the deficit will rise by $1.3trn over the next 10 years, thanks to the recent package). Jerome Powell, the new Fed chairman, will be far more important in determining the dollar’s direction than Mr Mnuchin.

How far can the dollar fall? Our Big Mac index suggests the currency is still overvalued, although less so than six months ago. Gold, often seen as an alternative to the dollar, has been rallying in recent weeks; there are also reports that the fall in cryptocurrencies is causing investors to switch to a more traditional safe haven.

The most likely catalysts for a dollar rally might be some international crisis (causing a retreat from emerging markets) or a surge in inflation that prompted the Fed to tighten policy quicker than markets expect. Be careful what you wish for.

Source: economist

The buck drops here