JOHN LEGERE, the lion-maned boss of T-Mobile, made his wireless firm the fastest-growing carrier in America by cutting prices and giving customers better deals than AT&T and Verizon, which he relentlessly mocked on Twitter as retrograde behemoths. His personal brand as an industry maverick may have helped too. On April 29th he put that image to the test, agreeing to a combination with Sprint, the next largest carrier after T-Mobile, and creating a behemoth under his leadership.

The deal, all in shares, values the combined entity at $146bn including debt. If approved by regulators, it would squeeze the number of providers in the wireless market in America from four to three. That is a big “if”—twice earlier this decade, antitrust authorities have either stepped in to prevent such an outcome or indicated that they would do so, for fear of higher prices for consumers.

-

Why has Qatar Airways just launched flights to Wales?

-

Young Americans believe in a vengeful God

-

Gay and women’s rights are remarkably a part of Lebanon’s elections

-

The art of doing something with nothing

-

Under the surface of Eisenhower’s era

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

Mr Legere presumably knows the challenge, so he appealed to the political priorities of President Donald Trump. First came a promise that the union with Sprint would add thousands of jobs in America (despite also promising shareholders $6bn of annual savings, mostly cost cuts). Second, he pledged that the two firms would spend $40bn within three years to build a national 5G mobile broadband network much more quickly than either Verizon or AT&T, by taking advantage of a combination of their spectrum assets. Mr Trump’s administration has made it clear that it covets early development of a 5G network, to stop China winning the battle over the technology. In addition, “Trump-led tax reform” was “particularly helpful” to the deal’s economics, cooed Mr Legere. Investors, worried that Mr Trump’s Department of Justice will not be so easily charmed, sold shares in both companies.

The deal represents a big retreat for Masayoshi Son, boss of SoftBank, which owns 85% of Sprint. Mr Son engineered a $20bn takeover of Sprint in 2013, with the aim of merging it with T-Mobile, but badly misjudged the regulatory mood. Twice he tried and failed to merge Sprint with T-Mobile and put Sprint in charge. Instead Sprint gave up its third-place position in the wireless market while consistently losing money, raising the spectre of bankruptcy.

Calling the deal a merger seems a face-saving gesture for Mr Son. The new company will be called T-Mobile, Mr Legere will run it and Deutsche Telekom, its parent firm, will own a plurality of shares. But SoftBank won better terms than analysts expected, getting 27% of the new company and four board seats, including one for Mr Son. He will be able to switch attention from Sprint to his new $100bn Vision Fund, a giant technology fund.

The two companies argue, with some support from analysts, that telecommunications companies increasingly need massive scale to succeed. AT&T and Verizon have more combined market share now than they did five years ago, at about 70%. (T-Mobile, with 16%, has gained market share mostly from Sprint, which has 12%.) AT&T is trying to buy Time Warner, pending a regulatory challenge (see article), in part to better lock in customers. Both AT&T and Verizon are investing in 5G. Mr Legere and Marcelo Claure, the boss of Sprint (pictured above), say that only by joining up can T-Mobile and Sprint compete against the larger firms.

Their claims about 5G do contain some truth. Combined, the two companies own enough spectrum to cover much of the country with a far zippier network than either has now, though not at the fastest speeds promised with 5G. “Sprint is bringing some serious spectrum assets that T-Mobile doesn’t have and really needs badly for 5G,” says Stéphane Téral of IHS Markit, a provider of market and financial data.

The new T-Mobile would be better and stronger, analysts say, but its prices would probably not be lower. Projections from T-Mobile and Sprint of sharply higher profit margins for the merged firm suggest another priority.

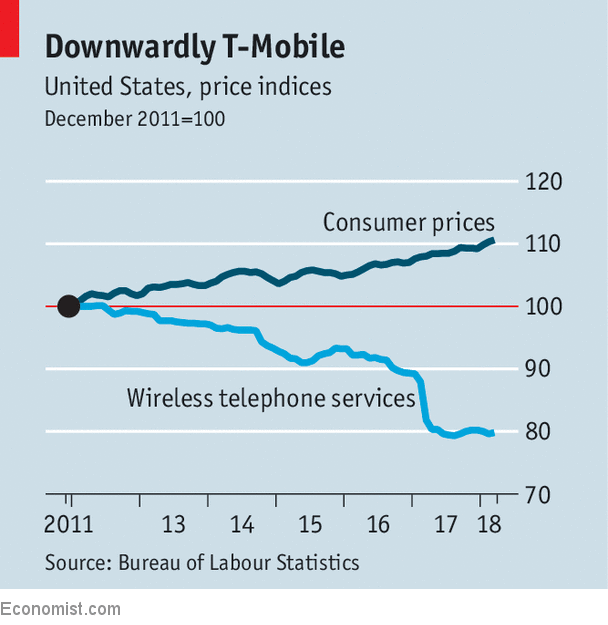

In 2011 regulators blocked an acquisition of T-Mobile by AT&T, and in 2014 they indicated to T-Mobile and Sprint that they believed the market still needed four carriers. Customers have benefited: monthly wireless bills for urban consumers have fallen by 20% since 2011 (see chart). Mr Legere’s success at T-Mobile, in fact, could be the merger’s undoing. T-Mobile appeared on the verge of collapse in late 2011 when regulators blocked the AT&T acquisition. Since 2013 it has thrived, adding 40m customers by getting rid of long-term contracts, reducing prices and offering unlimited data usage. Craig Moffett of MoffettNathanson writes that the justice department “undoubtedly feels vindicated by its 2011 decision”. He gives the merger a 50-50 chance of approval.

Source: economist

T-Mobile and Sprint chivvy regulators to bless their merger