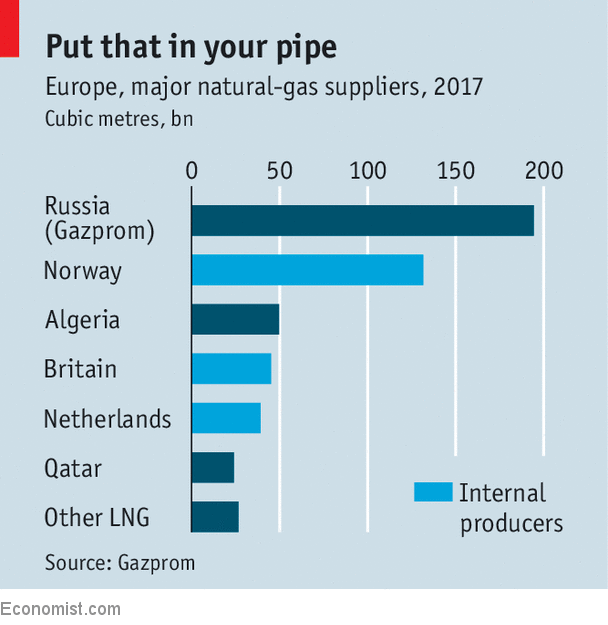

FEW firms have more power to heat up the cauldron of global geopolitics than Gazprom, the state-backed Russian energy producer. It supplies more than a third of the natural gas that Europeans use for power generation, heating and cooking, creating what many—especially Americans—see as an unhealthy dependence (see chart). It has used its strength to bully countries which are out of favour with the Kremlin, such as Ukraine and Poland. And it is engaged in a growing rivalry with American exporters of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Europe and China, a competition which potentially adds to the world’s trade tensions.

-

The Supreme Court sides with companies over arbitration agreements

-

Philip Roth was one of America’s greatest novelists

-

Alexa, who is God? A new app aims to win over agnostics

-

Gazprom is enjoying a sales boom in Europe

-

America is losing the battle against robocalls

-

Markets may be underpricing climate-related risk

The firm also revels in its bad-boy image. When its boss, Alexei Miller, was put on an American sanctions list in April because of his ties to President Vladimir Putin, he said: “Finally, I’ve been included. It means we are doing everything right.” In February it described to investors in a presentation slide how its gas exports to Europe were like a big cup of tea. America’s LNG exports to the continent, in contrast, were depicted as a couple of drops of water only visible under a magnifying glass.

Gazprom has reason to feel cocky. Back in 2014, as a result of the Ukraine crisis, it scrapped some pipeline deals to Europe amid tumbling export volumes. It also appeared to pivot east, announcing a $55bn pipeline investment to provide gas to China; the taps are due to be turned on next year. But since 2016 its supplies to Europe have surged to record levels, thanks to falling coal use in Europe, less natural-gas production in the Netherlands and a robust revival in energy demand.

Regulators may give it a further boost. This week Gazprom is expected to settle a long-standing dispute with European trustbusters, who have accused it of hindering the free flow of its gas in eight central and Eastern European countries and of charging customers too much. The agreement is likely to come with strings attached, such as a commitment by Gazprom to provide more market-driven pricing and to allow purchasers to sell on its gas to others. But that could also make its gas even more attractive to customers, says James Henderson of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, a research body. With cheap gas plentiful in Russia and the rouble weak, the main constraint it faces in supplying yet more gas to European customers is the lack of spare pipeline capacity.

That is why the Russian firm has agreed with five other European energy companies—Engie, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, Uniper and Wintershall—to double by next year the size of its undersea supply route to Germany through the proposed Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which will cost $11bn. It also plans a new Black Sea route to Europe via Turkey called TurkStream. Meanwhile, after an adverse tribunal ruling in Stockholm in February that left Gazprom owing more than $2.5bn to Ukraine’s energy company, Naftogaz (money due because Gazprom defaulted on a 2009-19 contract to supply minimum amounts of gas to Naftogaz, depriving it of transit revenue), it has scrapped plans to restart exports to Ukraine and has issued threats in the past to terminate its supply and transit contracts.

But that is where the American government could disrupt Gazprom’s streak of luck. Trump administration officials have threatened to impose sanctions on companies taking part with Gazprom in Nord Stream 2, worrying that this will strengthen Russia and leave Ukraine more exposed. They have also reportedly sought to force Germany to drop the project as part of ongoing negotiations on metals tariffs.

Russia suspects—probably rightly—that Mr Trump has specific energy goals as well as geopolitical ones. It says his government is trying to block the Nord Stream 2 pipeline in order to sell more American LNG to Europe. “Donald is not just the US president, he is also…promoting the interest of his business, to ensure the sales of LNG into the European market,” Mr Putin said.

Perhaps in a sign of compromise, Mr Putin and Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, have agreed that Gazprom gas should continue to flow via Ukraine. The flow could be lower than previously, but Mr Henderson says continued transit via Ukraine could provide Europe with important alternatives, whatever happens to the other proposed pipelines. As for Nord Stream 2, he says the rising geopolitical temperature may delay it. “But not for ever.” Gazprom has too much muscle to be thwarted altogether.

Source: economist

Gazprom is enjoying a sales boom in Europe