AS A citizen, Dave Jones worries that climate change may imperil his two children, and theirs in turn. What exercises him, as California’s insurance commissioner, is the way in which a transition to a low-carbon economy might affect the financial health of his other charges—the state’s 1,300-odd insurers. On May 8th Mr Jones unveiled an examination of how well the investment portfolios of the 672 insurers with $100m or more in annual premiums align with the Paris climate agreement of 2015, in which world leaders vowed to keep global warming below 2°C relative to pre-industrial times.

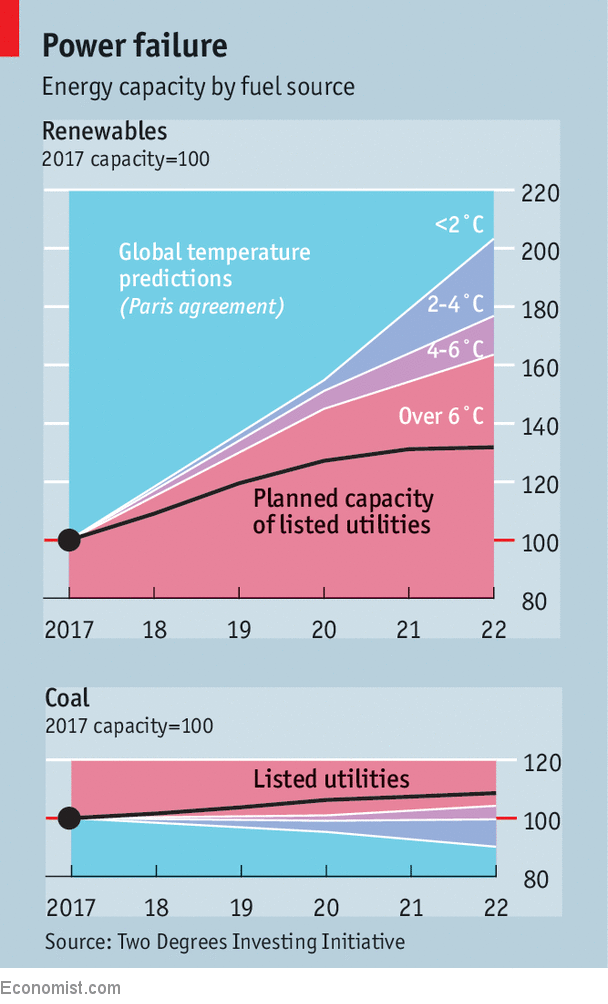

The answer is, not very. In the next five years carbon-intensive firms in the insurers’ portfolios plan to produce more internal combustion engines and coal-fired electricity than the maximum the International Energy Agency (IEA) reckons is compatible with meeting the 2°C goal (see chart). Meanwhile, investment plans in renewable energy and electric vehicles lag behind the IEA’s projections of what is needed.

-

The Supreme Court sides with companies over arbitration agreements

-

Philip Roth was one of America’s greatest novelists

-

Alexa, who is God? A new app aims to win over agnostics

-

Gazprom is enjoying a sales boom in Europe

-

America is losing the battle against robocalls

-

Markets may be underpricing climate-related risk

The results echo those of a study last year by Swiss authorities on the portfolios of pension funds and underwriters. According to the Two Degrees Investing Initiative, a think-tank that conducted climate stress tests for the Swiss and Californian regulators, global equity and corporate-bond markets also look dangerously exposed to energy-transition risk.

Such findings prompt talk of a “carbon bubble”— overvaluation of businesses that could suffer if the climate threat is tackled resolutely. A study this month in Environmental Research Letters by Alexander Pfeiffer of Oxford University and colleagues found that electricity producers would have to retire around 20% of existing capacity, and cancel all planned projects, if the Paris goals are to be met. Between 2009 and 2015 Moody’s cut the average credit rating of European power utilities by three notches. This was partly because of environmental risk, says Myriam Durand of Moody’s.

Last June the Financial Stability Board, a club of regulators, recommended that companies should assess and own up to the climate-related risks they face, including those from decarbonisation. Since last year institutional investors in France have been required to do so by law. In a letter published in the Financial Times on May 18th, 60 fund managers with a combined $10.4trn in assets urged the oil and gas industry to be “more transparent and take responsibility for all of its emissions”. On May 21st Christopher Hohn, a hedge-fund manager, wrote an open letter to the Bank of England warning that disclosure rules meant investors lacked the information they needed to assess the “serious climate-related risks” British banks are exposed to through their loan books.

But many investors seem unconcerned. At the annual meeting of Royal Dutch Shell shareholders on May 22nd, activist investors revived a resolution that would oblige the energy giant to align its business with the Paris agreement. As happened last year, the resolution was defeated. Shell contends that its assets are not at risk of being stranded. Other oil and gas companies are equally confident, judging by a report about climate planning by the eight biggest of them, published on the eve of the Shell meeting by Carbon Tracker, a watchdog. As its authors say, they cannot all be right.

Plenty of shareholders reckon that their companies will not suffer—or that they will be able to get out in time. Asset managers hold a stock or bond for 1.5 years on average. Short time horizons may explain why markets tend to brush off climate commitments. Neither the signing of the Paris agreement nor its ratification a year later had an impact on global energy stocks, according to a working paper by Thomas Sterner and Samson Mukanjari of Gothenburg University, perhaps because these events had already been priced in. Or, just as likely, markets never believed the commitments.

If promised climate action did come to naught, however, risk would return to strike investors in other ways. Assets may be ravaged by rising sea levels or other climate calamities. Or companies may be sued for their role in bringing these about. On May 24th a federal court in California is due to decide whether to dismiss a case brought by Oakland and San Francisco against oil majors, including Shell, for the harm done to the cities by an encroaching ocean. Mr Jones will not be the only one watching closely.

Source: economist

Markets may be underpricing climate-related risk