THE single-storey main branch of the Texas Hill Country Bank, in Kerrville, sits at the back of a tired shopping centre, in the shade of a six-storey Wells Fargo building. When Roy Thompson, the chief executive, was hired (from Wells) in 2012, three years after it opened, he ran a radio ad campaign to alert locals to its existence. It asked listeners to help a mother (his) to find her child (Roy himself), who had gone missing after joining a community bank.

-

The campaign to decolonise culture in Britain

-

On free speech, liberal dinosaurs, universal basic income and a video contest

-

Why Democrats are worried about California

-

America is good at dealing with hurricanes on the mainland—after they strike

-

Do we pay nurses less because we envy them? Unlikely

-

How to convince sceptics of the value of immigration?

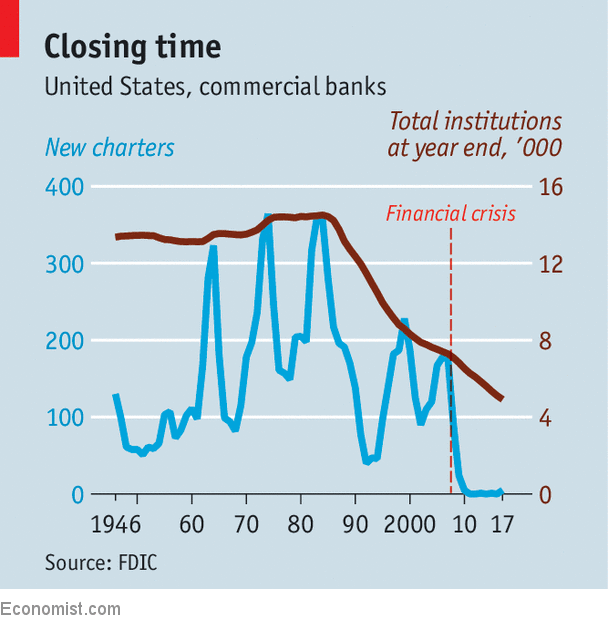

If Mr Thompson had shared the fate of many small-town bankers, he would have remained missing. Since 2012 more than 2,000 American banks have closed (see chart). Almost all were small, operating in the shadows of big banks with big budgets for marketing, technology and regulatory compliance. For the same reasons, almost no new banks have opened. Before the crisis the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) approved hundreds of bank charters each year. Since 2009 there have been only a dozen in total.

So sudden has been the stop that the FDIC is seeking to encourage new banks to open. In 2017 it published “A Handbook for Organisers of De Novo Institutions”. It has held seminars on how to set up a bank in seven cities. But few would-be bankers have heeded the call. Only 12 applications for banking licences are pending.

West Texas is a shining exception. Texas Hill Country has grown steadily since it was founded in 2009. Though Kerrville residents still come up to Mr Thompson in the street to declare him found, in reality they all know where, and who, he is. On a tour of town he explains who owns this lumber yard, that car-repair shop, the other medical centre—he has provided them all with financing, or else hopes to.

Texas Hill Country was the creation of J. Bruce Bugg, a tax lawyer who put himself through college with jobs in banks. In 1989, aged 29, he bought a bank and sold it at a profit. In 2007 he returned to the business, founding the Bank of San Antonio, followed by Texas Hill and, last year, the Bank of Austin. In the 1980s many Texan banks had been taken over after a previous financial crisis. After the crisis of 2008, distant headquarters closed branches and turned away staff. Banks were “inviting their customers out the door”, says Mr Bugg—and he was there to scoop them up.

Today, the Bank of San Antonio no longer counts as small, with $800m in assets. Return on equity is more than 12%. Texas Hill has $117m in assets and return on equity is a still-respectable 8.9%. Their success meant Mr Bugg was easily able to raise money for the Bank of Austin, which is on track to be profitable soon. Half of its 120 shareholders were keen enough to show up for its first annual meeting on May 15th.

Small banks, as new banks inevitably are, face great challenges. But they are easing. Regulations tightened after the crisis have been loosened for smaller institutions. The cost of technology is falling. The Bugg banks’ electronic spine is from Jack Henry & Associates, a provider of IT services to financial institutions. Its share price has risen six-fold since the crisis.

And new banks also have advantages, Mr Bugg contends: no bad assets, demoralised employees or outmoded technology, plus strong local connections. Each of his three banks is separately capitalised with local shareholders—businesspeople who act as ambassadors. Each is managed by an experienced escapee from a large bank, who, through stock options, can own up to 5% of the institution they lead. The model Mr Bugg is developing has no patent. Community banking may be due a revival.

Source: economist

The number of new banks in America has fallen off a cliff